“A Practical Fanatic”

Sam Tanenhaus first met William F. Buckley Jr. in 1990. Tanenhaus was then working on a biography of Whittaker Chambers, the ex-communist Time magazine writer who, in 1948, accused Alger Hiss, a well-bred former State Department official, of being a Soviet spy. Buckley had championed, defended, and patronized Chambers — who was badly treated by the liberal press — publishing his work in National Review and seeking Chambers’ guidance as Buckley undertook his own war with mid-century liberal self-satisfaction. The two men remained close friends until Chambers’ death, at age 60, in 1961.

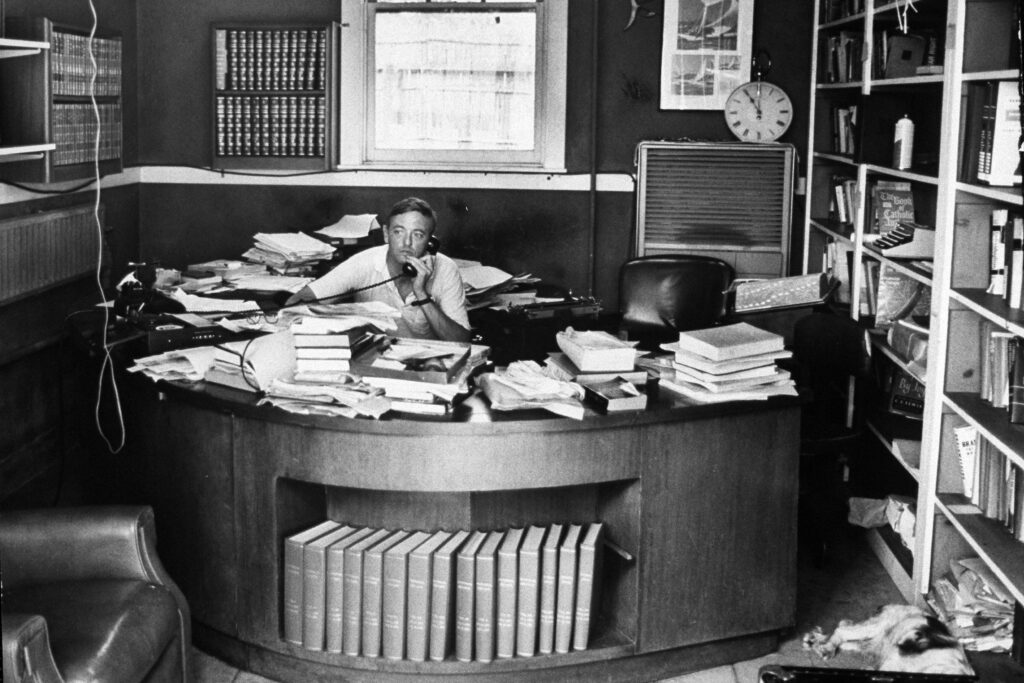

Tanenhaus hoped Buckley would cooperate with his book. “He did much more than that,” Tanenhaus recalled, “Like so many others, I discovered the great breadth of Buckley’s generosity and the almost limitless reach of his friendships and connections.” Before long, Buckley was opening doors for the young biographer, making introductions, finding him grant money, and performing “innumerable other kindnesses, large and small.” Like almost everyone who came into contact with Buckley, Tanenhaus was charmed Before he’d finished the book on Chambers, he had already decided on his next biographical subject: Buckley himself.

Thirty-five years later, the fruit of that first encounter — “fun and memorable,” Tanenhaus reports, like all the rest — has been published by Random House: a 1000-page cinderblock of a book entitled Buckley: The Life and The Revolution that Changed America. The book is a serious accomplishment: a detailed, artful, moving, and tactfully ambivalent appreciation of a legitimately towering figure in the cultural and political life of the second half of the 20th century. Through the strength of his personality and will, Buckley transformed the American right — in the eyes of the public — from a sordid, benighted affair, undertaken by paranoid eccentrics and venal tycoons, into a respectable political movement with intellectual foundations and literary flare. For much of his life, Buckley and American conservatism were synonymous, and both benefited from the association. But the years since his death, in 2008, have strained the reputation of the movement he built, causing many to question whether it ever deserved the respectability Buckley claimed on its behalf.

As also evidenced by his Chambers book, Tanenhaus is a fine and graceful writer, talented at intellectual synthesis, attuned to idiosyncrasy and irony, diligent about situating his subjects in the larger sweep of history. Despite the 27 years he spent with Buckley, Tanenhaus has not succumbed to the biographer’s inclination to either vindicate or prosecute his subject. Rather, he is magnanimous, patient, and needling — brotherly, perhaps — in much the manner of Buckley, whose tolerance for countless brilliant, irksome, malignant mentors and friends (an inexhaustive list: Joe McCarthy, Willmoore Kendall, Willi Schlamm, Brent Bozell, Roy Cohn, Howard Hunt) was storied. Most important perhaps, Tanenhaus is endowed with the literary biographer’s essential triumvirate of sensitivities: to ideological dilemma; to psychology and its roots in the family romance; and to gossip.

Buckley (“Bill” to those who knew him) was born November 24, 1925, the sixth of ten children, all raised at “Great Elm,” a sprawling compound in Sharon, Connecticut (with formative sojourns to the family’s other estate, “Kamschatka,” in Camden, South Carolina). Devout Catholics with continental pretensions — Bill learned Spanish and French before English — the Buckleys were a mischievous and musical bunch who stood out in staid, protestant New England. From his father, Willam F. Buckley Sr. (“Will”), an oil speculator from Texas who dabbled in various counterrevolutionary plots in Mexico before his expulsion in 1920, Bill inherited politics — Will’s were Anglophobic, anticommunist, antisemitic, and implacably isolationist — and a lifelong weakness for intrigues, gambling, and get-rich schemes. From his attractive mother, Aloise, who was, Tanenhaus writes, “ever just out of reach,” Buckley inherited piety and his fathomless need to please, entertain, and captivate.

Will’s Jew-hatred was ingrained enough that his elder children — 11-year-old Bill was excluded — burned a cross on the lawn of a Jewish resort in 1937. “I wept tears of frustration,” Bill Buckley recalled many years later, over being excluded from this “great lark.” Buckley’s childhood esteem for Charles Lindbergh was also untroubled by the latter’s forays into Hitlerism.

A precocious but undisciplined student, Buckley eventually found his passion in speech and debate. In 1943, the headmaster at Millbrook School, from whom Bill was constantly seeking special favors and licenses, assessed his brilliant pupil thus:

Bill is an extremely interesting boy with great potentialities. At the moment I should say his mind is almost too sharp for his own good. He tends to be egotistical and intolerant. Because of these tendencies he is not as popular a person as was his brother Jim, whose geniality won everybody’s affection. Bill is more the cold, calculating and self-seeking person, although perhaps those words are too strong in their critical implication.

Buckley served two years in the Army (he was never sent overseas) before entering Yale in 1946, where he became the chairman of the Yale Daily News. In 1950, he married Pat Taylor, his sister Trish’s Vassar roommate and the daughter of wealthy Vancouver industrialists (far more so than the boom-or-bust Buckleys). Before their first date, Bill — “who had grown up in a home full of sisters,” writes Tanenhaus — painted Pat’s nails while she finished a phone call in her dorm room: a premonition of their long, charming, campy partnership.

Bill was a sensation in New Haven, the campus’s “uncrowned prince,” embarrassing liberal rivals in debate (alongside his soon-to-be brother-in-law Brent Bozell) and turning the opinion page of the News into a shocking, must-read venue for reactionary juvenilia. In a valedictory editorial at the end of his chairmanship, Buckley wrote, “We are the first to admit that ours is not the art of persuasion. We deeply bemoan our inability to allure without antagonizing, to seduce without violating. Especially because we believe in what we preached and would have liked very much for our vision to have been contagious.” These deficiencies he would seek to rectify — with only partial success — when he started his own magazine.

Buckley seduced many of his instructors, including those whose politics he abhorred and vice versa, but none more so than the obstreperous ex-communist political scientist Willmoore Kendall. Kendall’s ideas would provide the intellectual backbone to Bill’s first three books: God and Man At Yale (1951), McCarthy and His Enemies (1954; written with Bozell), and Up From Liberalism (1959). The son of a forbidding Methodist preacher in Oklahoma, Kendall believed in the majority’s unassailable right — obligation, even — to vigorously enforce a moral orthodoxy in the body politic; McCarthyism, for Bill and Brent, was one expression of that privilege. The Yale administration’s (largely unexercised) right to ban its instructors from teaching Marxism and other unchristian theories was another. As Kendall would later write, “The true American tradition is less that of Fourth of July orations and our constitutional law textbooks, with their cluck-clucking over the so-called preferred freedoms, than, quite simply, that of riding somebody out of town on a rail.”

Bill was never a stickler for facts — as a debater, he judged information by its usefulness not its truth value — and from Kendall, an O.S.S. officer during WWII, Buckley learned a more sophisticated justification for his innate carelessness: psychological warfare. It didn’t matter that McCarthy was a heedless font of calumny; “slanders and smears were best understood as strategically useful,” writes Tanenhaus, “perhaps even necessary disinformation.” That McCarthy damaged and demoralized the enemy was reason enough to back him. Asked in 2019 why Buckley and company never seemed to care about McCarthy’s lies, George Will told Tanenhaus, “I think it’s grounded in the oppositional mentality. The feeling that we are a church militant in an unconverted world and we have to watch our back.”

In 1951, Buckley got his own taste of intelligence work: a brief stint in the CIA, arranged by Kendall with aid from a new mentor, the ex-Trotskyist philosopher James (“Jim”) Burnham. Buckley was stationed in Mexico City, where he lived across the street from Diego Rivera (apparently not his target). Among other assignments, Buckley helped a Peruvian ex-communist write his memoirs of disillusionment — in CIA-approved verbiage. Buckley’s accomplice in clandestine activity was Howard Hunt, who was stationed in Mexico to bug the offices of Iron Curtain embassies. But according to Tanenhaus, “their collaboration consisting mainly of delicious lunches and free-flowing alcohol at La Normandia — ‘the only good French restaurant in Mexico City,’ in the opinion of Hunt.” Though a “braggart and showoff,” Buckley found Hunt “tremendously good company.” During Watergate, Buckley, who had stayed in touch with Hunt, knew much more than he let on, but he kept mum — one of many semi-criminal omissions indulged out of loyalty to a friend.

McCarthy didn’t care much for the book Bill and Brent wrote on his behalf. “It’s too intellectual for me,” he told Trish Bozell (Buckley’s sister married Brent). But the Joe McCarthys of the world were not its intended audience. McCarthy and His Enemies was a conscious effort to lacquer over Joe’s vulgar demagogy with a shiny coat of Ivy League sophistry. Bill and Brent, with Kendall’s help, hoped to elevate the conversation, infuse it with philosophical dimensions, and thereby induce the bien pensant chattering classes to take McCarthy — or at least his crusade — seriously. Reviewers saw through the charade. (“McCarthy’s Eggheads” they were dubbed.) The effect was bathetic. “A laborious piece of special pleading,” was Dwight MacDonald’s judgment, “which gives the general effect of a brief by Cadwalader, Wickersham and Taft on behalf of a pickpocket caught in the men’s room of the subway.”

But Buckley loved McCarthy, recognizing him for what he was: a vestige of the Old Right, Buckley’s father’s world. “The carnal hunt for enemies within,” writes Tanenhaus, “the unmasking of their apologists and allies, real and more often fanciful, brought together diverse factions of a weak and fragmented movement in the growing war against the New Deal and its aftermath.” These same carnal energies would need to be summoned for a new era. But to be efficacious they would need to be channeled. Buckley had a deep and abiding love for cranky ideologues and weirdos; not everyone in America would. It was easy enough to be skunks at the garden party of midcentury liberalism; Buckley aspired to host his own fête champêtre. His would be a practical fanaticism, Tanenhaus argues. Notably, it was McCarthy’s graceless, bullying manner during the televised Army-McCarthy hearings that decisively turned the public against him. Buckley, with his quick-footed elegance and wit, his thousand-watt grin, was well positioned to take up the mantle of conservatism for a televisual era. As master of ceremonies, Buckley was always trying to strike a balance: between old right and new; literary ornament and straight talk; intellectual reasoning and populist venom; high ideas and low tactics. With McCarthy and His Enemies, he hadn’t titrated the mixture correctly. (It was a “flop,” Buckley said.) With his next endeavor, he would get it right.

Because there is something wrong with me, accounts of National Review’s founding always get my blood pumping — like it’s the montage in a heist movie where the leader is “getting a team together.” (Ringleader: Buckley. Lancer: Bozell. Driver: Bill Rusher. Gunman: Frank Meyer. Explosives: Willmoore Kendall.) The story is told here in grainy detail. Tanenhaus is especially keen to emphasize the role played by the impetuous Viennese ex-Leninist Willi Schlamm, with whom Buckley “fell into giddy collusion” in the spring of 1954. It was Schlamm who insisted their magazine “must sing and dance and enthuse; it must have the scope (and the size) to create a climate of its own.” Schlamm, however, was another of Buckley’s cranks, “charming but quarrelsome, generous but thin-skinned, expansive when things went his way, touchily defensive, even volatile, when they did not.” And he tested even Buckley’s legendary patience. When Schlamm quit the magazine in July 1957 — after losing an acrimonious debate to the masthead’s other top dialectician, Burnham — Buckley expressed rare resignation: “The matter is one of pathology, and I am an editor, not a doctor.”

Tanenhaus dwells less on the philosophical debates that animated the magazine’s early years — George H. Nash’s The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945 (1976) remains the indispensable volume on that score — but he provides a much needed genealogy of the magazine’s early position on race and civil rights, linking the NR line to Buckley’s familial ties to the south. Readers may know of NR’s notorious 1957 editorial, “The South Must Prevail,” in which Buckley declared that White Southerners were “entitled to take such measures, politically and culturally, as are necessary to prevail in areas in which it does not predominate numerically” (i.e. suppress the vote) because they were “for the time being, the advanced race.” But Tanenhaus reveals the degree to which the magazine served, in the 50s and early 60s, as a genteel mouthpiece for Jim Crow, facilitating the ignominious revival of John C. Calhoun thought. “[Bill] is for segregation and backs it in every issue,” boasted Will Buckley peré to his friend Strom Thurmond. (Another revelation: the Buckleys of Camden funded a local paper that was the mouthpiece of the white Citizen’s Council.) As the Straussian Lincoln scholar — and Buckley’s friend — Harry Jaffa observed in 2010, “The origins of American conservatism is the ideology of the Old South in the 1860s. It never changed.”

In the canonical account, Buckley’s accomplishment was to bring traditionalists like Russell Kirk and libertarians like Frank Meyer under one roof, holding them together with the mortar of anticommunism — a compact given the name “fusionism.” But for Tanenhaus, anticommunism was more like the whole brick. The men who founded National Review, in his telling, were not just opponents of the USSR. They were McCarthyites. It is fascinating, then, that the person Buckley most desperately longed to bring into the fold was not one. Whittaker Chambers was terrified of McCarthy, warned Bill against him, and sensed that National Review — a magazine for conservative radicals — might not be a hospitable environment for someone whose political north stars were stability, pragmatism, and tragedy. Against Bill’s ideological stridency, Chambers advocated “the Beaconsfield position,” that is, Disraelian moderation. Nonetheless, he allowed Bill to visit him at his farm in Maryland and was, Tanenhaus writes, “enchanted, like so many other elders, by Buckley’s ease of manner, the unaffected cordiality, his ‘special grace.’” Their courtship continued for several years, with Chambers resisting without ever quite rebuffing Buckley’s advances. “I believe that you will be more successful without me,” Chambers insisted, while adding, “I shall not quickly forget, either, that you, and you alone, generously offered me something in this world.”

The Chambers/Buckley relationship is moving in its tenderness; it shows Buckley in his best light. “Bill understood loneliness and intuitively sensed it in others,” writes Tanenhaus. Bill’s letters to Chambers could be over-the-top: “It has long been the irrevocable consensus in my numerous family (ten brothers and sisters) that your courage, your skills, and your faith are the brightest beacon of the free world.” But that mix of tactful ingratiation and brazen sentimentality was Buckley’s gift. His manipulative tendencies were tempered by their transparency. He was a flirt and a flatterer but not covertly so. If Bill was capable of manipulation — and he was — it is only because he understood the barely concealed desire, in most men, to be put to use. And Chambers wanted to be wooed. Chambers would eventually contribute to the magazine and even, for a time, attend editorial meetings in the New York office, where he was “surprisingly jovial presence.”

The depth of the Chambers/Buckley material, and their contrasting characters, points to one of my reservations about the book, however.

Tanenhaus’s accomplishment in the Chambers bio was to uncover the depth of his subject’s torment, the tragic, fate-haunted life, which cultivated a tragic sensibility, in his politics and his prose. Chambers’s brother, who died by suicide, once wrote to his sibling, “We’re hopeless people. We can’t cope with the world. We’re too gentle.” And the same could be said of the Chambers we meet in Tanenhaus’s book. Buckley does not have these fate-haunted depths. Buckley’s is a story about a man who gets almost everything he wants, who is constantly having it both ways, and who pays very little price for doing so. (My girlfriend, the writer Hannah Gold, said Buckley reminds her of one of the overgrown Fauntleroy suspects on Columbo – except Buckley gets away with the murder.)

As a biographical subject, there is a risk that Buckley isn’t large enough, the soul too unburdened by pathos, the brilliance lacking. Bill was a great dazzler — “an intellectual entertainer” — and a capable organizer, networker, and mover of men. As his profile grew, audiences were always “alive to his particular music: the arcane vocabulary and ornate syntax, the fanciful imagery, the irony, the weave of logic and sophistry.” Buckley’s readers and fans enjoyed the show, and he repaid their esteem by never talking down to them. But he was not a great thinker, a great artist, or a great soul. He was “an aesthete of controversy,” writes Tanenhaus, “rather than a theorist.” He never wrote a great book. His accomplishments are historical and organizational, not intellectual or artistic. And at times, they evince a small, grubby quality. They are no match, in literary interest, for the morose and tragic genius of a Whittaker Chambers.

But then, the reason for Buckley’s dogged pursuit of Chambers is that he, like Tanenhaus, saw the vastness in him — a depth that he lacked and therefore coveted in others. Buckley, for all his arrogance, was the rare history-making figure who succeeded by reckoning his own limitations. “The challenge,” Buckley wrote of sailing, his other great passion, “lies in setting the sails as quickly as you know how, in trimming them as well as you know how; in handling the helm as well as you can; in getting as good a fix as you can; in devising the soundest and subtlest strategy given your own horizons…” What Buckley lacked in pathos, and genius, he made up for in his acute sensitivity to these qualities in others. His gift was his febrile admiration, his boyish intensity of affection. It was in the flattering light of Bill Buckley’s admiration that so many men were moved to put their own genius in service of his cause. (It is for this reason, too, that Buckley was so pained by the apostasy of brilliant writers like Garry Wills, whose zeal for the cause wavered as their genius grew.)

I have dwelled here on the early portions of the life because I am preoccupied with origins. But there is a great deal of fascinating material in the meat of the book: on the Goldwater campaign; on Buckley’s run for mayor in 1965; on Firing Line and Bill’s crossover fame; on those two fateful debates in the 1960s, with James Baldwin and Gore Vidal; on Watergate; on his love, support, and mentorship of Ronald Reagan. To my surprise, the book’s first 834 pages deposit the reader just inside Reagan’s second term. Another 26 speedy pages cover the years from 1986 to 2008. Tanenhaus’s apparent justification for this imbalance is that Buckley’s most important work was done. Having succeeded in establishing a “new consensus,” Tanenhaus writes, “in his last years he came to seem less ideologue than public institution and at times figure of fun.”

That Buckley took so long to complete — Tanenhaus spent nine of the intervening years as editor of the New York Times Book Review — will have a curious effect on its reception. Since Buckley’s death, in February 2008, his legacy has undergone several renovations. The George W. Bush era, and especially the financial crisis which punctuated it, badly damaged the brand of market fundamentalism championed by Buckley and his acolytes. In February 2009, Tanenhaus himself wrote a long essay in The New Republic (later released as a short book) summarizing the ups and downs of post-war conservatism, concluding with a harsh verdict, announced by the headline it ran under: “Conservatism is Dead.” The Iraq War — from which Buckley, to his credit, was a relatively early defector — also damaged the reputations of the neo-conservatives with whom he otherwise found common cause in his later years.

The revanchist counterrevolution that Buckley set in motion, Tanenhaus argues, had exhausted and disgraced itself in the failures of Bush II. Rather, it was the newly elected Democratic president, Barack Obama, whose prudential politics of adjustment more closely approximated the Burkean side of conservatism, who might’ve agreed with Chambers that “to live is to maneuver.” But Obama’s presidency quickly gave rise to a new wave of revanchist zeal. The Tea Party’s free market faith was at least as pure as Buckley’s; they injected much needed verve and grassroots energy into the senescent institutions of Buckleyite conservatism, which might otherwise have perished along with their architect.

The confusion was compounded again with the rise of Donald Trump in 2016. For large portions of the conservative movement — including, initially, the masthead of National Review — Trump represented a perversion of the conservatism to which Buckley had given voice. Where Buckley was urbane and literary, a cosmopolitan polyglot who spent his winters skiing and writing novels in Switzerland, Trump was vulgar, unlearned, and anti-intellectual; where Buckley was devoutly Catholic and sexually conservative, Trump was unbelieving, deviant, and serially unfaithful; where Buckley disdained the welfare state, Trump promised to protect Medicare and Social Security.

Most importantly for his early conservative detractors, Trump seemed to represent a revival of ugly impulses on the right that Buckley was supposed to have contained. In their whiggish court histories, NR conservatives memorialized Buckey as the movement’s gatekeeper, the guardian of its respectability. In this telling, it was Buckley who (prudently) excluded the overly conspiratorial John Birchers, the intransigently racist George Wallace clique, the antisemitic and nativist paleoconservatives. Trump, with his populism, his anti-immigrant racism, his “America First” military and trade policies, augured the return of an older, coarser right, the tactful suppression of which was supposed to have been Buckley’s great achievement. Of course, when it turned out that Trump’s paleo themes were perfectly in tune with the anxieties of a winning coalition of voters — not an atavistic albatross for the Party, but an innovative and badly-needed path forward — the reservations of many members of the NR crowd evaporated.

But this “guardrails” interpretation of Buckley’s role has been repeatedly challenged. On the left, historians like David Austin Walsh have suggested that Buckley maintained many more associations (and sympathies) with the radical fringe than court historians of conservatism would have us believe. In other words, what guardrails? On the right, there are followers of figures like Pat Buchanan and Sam Francis who would say, yes, Buckley endeavored to undermine the disreputable right, but he failed, and thank God — his respectability politics were always a cowardly error, undertaken to preserve his good standing with Manhattanite liberals. And yet another view is that Buckley did a good job suppressing the nativist, isolationist, and populist elements of the right; it was only after his death that Trumpism became possible. As Helen Andrews writes in Compact, “he managed to clamp down on ideas that would otherwise have found democratic representation in the Republican Party years earlier. Once he was gone, his successors tried to use the same tricks but could not make them work.”

There is ample fodder for any and all of these positions to be found in Tanenhaus’s impressive book. There is little doubt that Buckley left his imprint on the nation, but it’s not easy to say precisely what sort. “In his time, as in our own, no one really could say what American conservatism was or ought to be,” writes Tanenhaus. “Buckley himself repeatedly tried to and at last gave up.” In the flamboyant memoirs he wrote toward the end of his life, he “made his ‘conservative demonstration,’ not as creed but as mode of living and being.” Conservatism, then, for Buckley, consisted of living and savoring life fully — within limits. Whether such a demonstration could possibly be of any use to most readers, who must maneuver within much tighter confines than his own, is hard to say. Perhaps what he really offered, like Trump, was a satisfying vicarious fantasy — for those who would never ski at Gstaad, sail the Atlantic, juggle appointments with John Kenneth Galbraith and Milton Friedman, or swim in “the most beautiful indoor swimming pool this side of Pompeii” (located in the Buckleys’ basement).

He was certainly a pioneer of politics as entertainment; it’s no coincidence that the man who served as vessel for Buckley’s political ambitions — Ronnie — was our first Hollywood president. More so than today’s conservative writers, I see MAGA celebrities like Turning Points USA’s Charlie Kirk, who is both an entertainer and a highly disciplined organizer, as Buckley’s descendants. To be sure, Buckley loved prose; it’s no accident that NR published early work by Wills, Joan Didion, John Leonard, Guy Davenport, and Arlene Croce. (Tanenhaus quotes Bill Rusher: “I always said it was a good thing The Communist Manifeso wasn’t well written… or we would have lost Buckley.”) But literary inclinations were largely bred out of subsequent generations of conservatives. What has remained is Buckley’s theatrical savvy: the ideological pugilism of Firing Line, the instinct for drama, the subtle mockery and playfulness. It’s notable that one of the most promising right-wing prose stylists of 1990s — Tucker Carlson — stopped writing for magazines to become a master of the cable form.

Like many of his heirs, Buckley’s worst quality was his dishonesty. Reckless slander and deceit were part of his toolkit from the start. What is notable, however, is how often he deployed these vices in service of one of his more stirring virtues: his intense loyalty and devotion to his friends. The coincidence of these two qualities could achieve parodic heights. When Roy Cohn was dying of AIDS and facing disbarment, Bill testified on his behalf: “He is absolutely impeccable. Not only would I have to forage within my own memory for any example of a lack of integrity, I would find it a priori inconceivable.” (Donald Trump also vouched for his old friend and mentor.) It isn’t surprising Buckley struggled to articulate a positive program for conservatism. When so much of one’s life is spent granting exceptions, it can be hard to remain clear on what the principles are.

There is a heedlessness to Buckley’s way of living — his craving for “action and distraction, to be in constant motion” — which simultaneously inspires, exhausts, and disquiets. Was he running from something? Or did he just enjoy watching the scenery go by? Buckley is the story of a happy, beloved man who made the world more coarse – and didn’t regret it. In this way, it’s unsatisfying. But Buckley wouldn’t have been Buckley if he had been more susceptible to introspection, doubt, or gloom. “Like F. Scott Fitzgerald,” writes Tanenhaus, “a writer he admired and identified with, Buckley was loath to give up his unwariness — an aspect of faith and also, as he found repeatedly, of faith’s dark twin, delusion. He was not always able to distinguish one from the other, but in that he was far from alone.”

Sam Adler-Bell is a freelance writer, columnist for New York Magazine, and cohost of “Know Your Enemy,” a podcast about the American right.