Will Davies has become one of the finest essayists in the English language on a variety of themes ranging from political economy to political culture. For The Ideas Letter 49, Davies focuses his mind … on the face, and how different “facial regimes” express forms of both agency and subjection. So rich are Davies’s observations that multiple research programs will likely emerge from his conceptions.

We are also honored to spotlight a coruscatingly sharp essay on power in its most naked and perverse form. Assaf Bondy and Adam Raz assess the political economy of complicity in Israel, an eye-opening analysis of how Israel not only manufactures consent but purchases it.

Our curated essays lead off with an interview with the Finnish intellectual historian Mikko Immanen, who offers an immanent (sorry!) critique of the thought of the Frankfurt School legend Theodor Adorno. The political scientist and cultural theorist Hisham Aidi, in the legendary journal Souffles, which he has revived, then offers a clarifying introduction to the magazine’s latest number on the boundaries of the Arab and African worlds. And we feature the law professor Joan Williams, who through the noted concept of “post-materialism” looks at the shifting dynamics of class politics in the United States.

Our musical selection for Issue 49 takes us back to 1980, when Jim Carroll, an American poet (he’s best known for The Basketball Diaries), recorded his debut record, a brilliant LP entitled Catholic Boy. The standout track is “People Who Died,” about Carroll’s many friends who suffered tragic early deaths. You’d think the song would be a dirge, but it’s actually uplifting, even anthemic, in its musical power. Lou Reed meets Patti Smith at the start of Reagan’s Thermidor.

—Leonard Benardo, senior vice president at the Open Society Foundations

Facial Recognitions

William Davies

The Ideas Letter

Essay

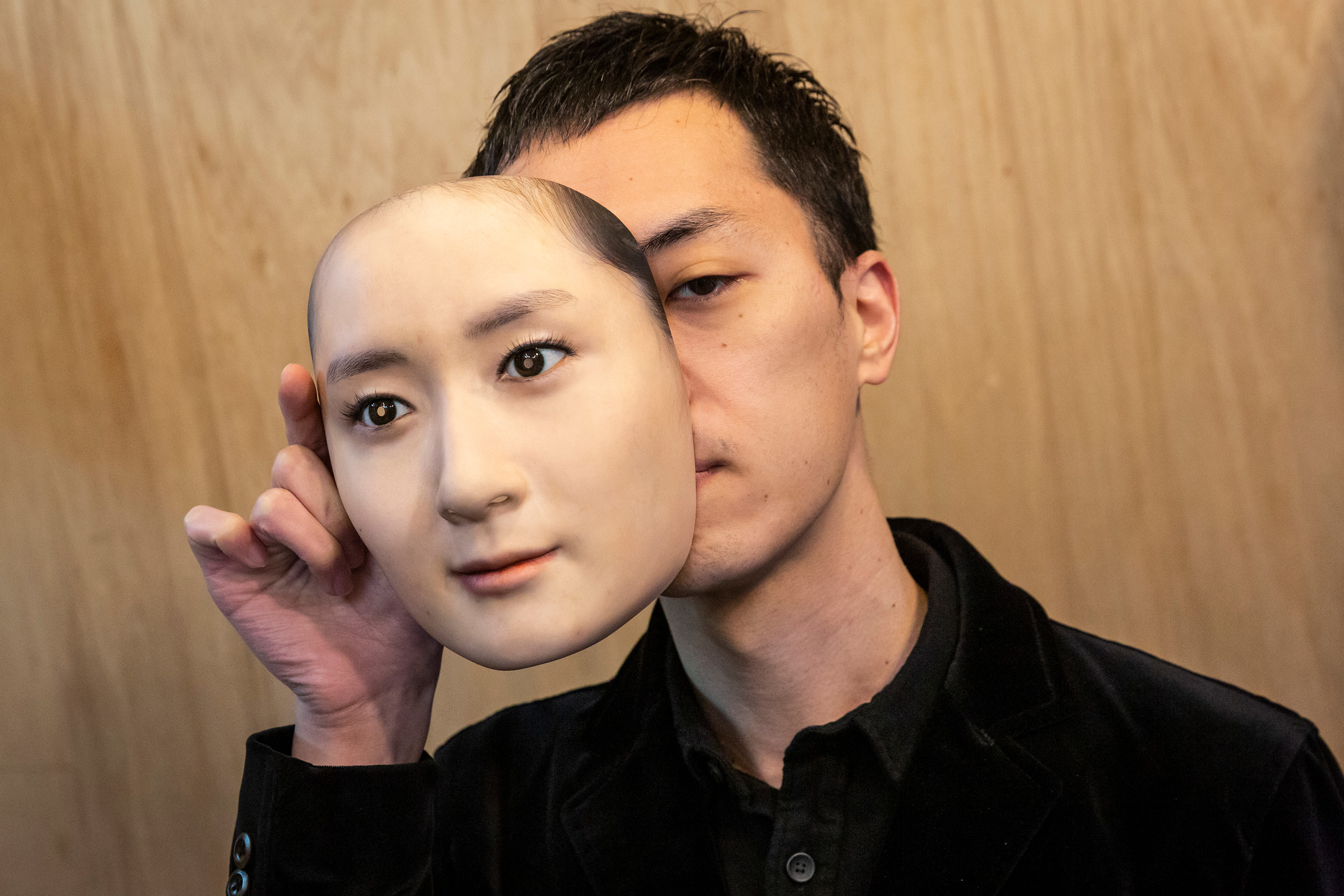

Davies traces the political history of the human face, showing how it has become both a weapon and a site of contestation—from far-right mobilizations fueled by viral images to the rancorous disputes over masks and veils that mark the politics of visibility in Europe. At once an object of surveillance and a conduit of recognition, the face is increasingly instrumentalized by digital platforms and state technologies of control. Yet, as he reminds us, the simple act of meeting face-to-face remains indispensable for easing social fractures, even as the very conditions that allow such encounters grow more fragile.

“As individuals become more exposed to surveillance—and therefore more classifiable—so power disappears from view. The politics of masking that has reverberated in Trump’s second term is a case in point: the banning of masks among Columbia students is of a piece with the fearsome visual anonymity of ICE agents, defended by the Trump administration on the basis that these agents are vulnerable to being doxed. Who gets to mask and who doesn’t is a basic index of political hierarchy in an age of ubiquitous videography and facial recognition. By this same logic, the adoption of masks by protesters is not only self-interested (though it may be that, when they’re exposed to the threat of prosecution or punishment) but a means of dissolving their identities into a collective bloc, with aspirations to power.”

The Economics of Complicity

How Israel Is Buying the Destruction of Gaza

Assaf Bondy and Adam Raz

The Ideas Letter

Essay

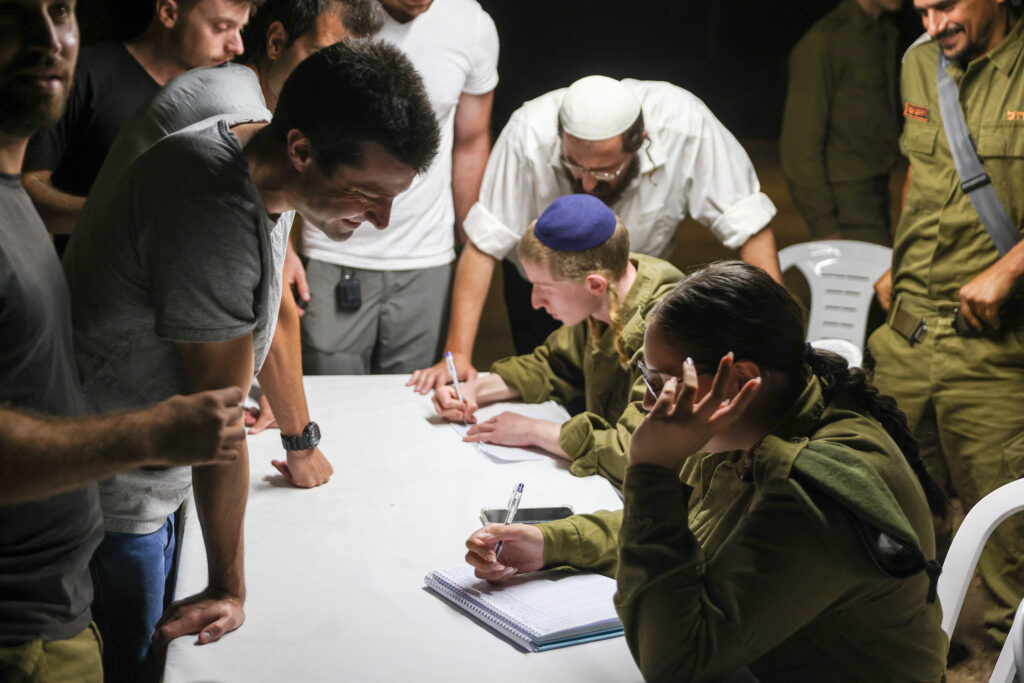

The dramatic evolution of Israeli reservists from unprecedented protest before the October 7 attacks to near-total compliance with the Netanyahu administration’s campaign in Gaza cannot be explained by trauma alone. The government has created what Bondy and Raz identify as twin “cages”—discursive euphemisms that normalize brutality and an economic set-up based on “reserve duty day” payments that transforms military service into a lucrative gig economy. Together, these mechanisms have woven complicity into the fabric of everyday life, threatening to recast the very social contract of Israeli democracy around participation in state crimes.

“The broader implications for Israeli society are profound. The traditional citizen-soldier model maintained clear distinctions between the civilian and the military spheres; military service was a civic duty, not a gig. When some of the most attractive economic opportunities in a society exist within military structures, and when military operations generate the income necessary for middle-class stability, the boundary between civilian and military dissolves. And when military operations then involve war crimes and other crimes, society becomes structurally invested in the military’s criminal policies. The hundreds of thousands of Israelis now directly dependent on this system, as well as on the broader social networks they represent, constitute a powerful constituency for the continuation of the Israeli government’s policies in Gaza regardless of these policies’ strategic effectiveness, any moral considerations about them, or international legal obligations.”

Why Adorno Read His Enemies

An Interview with Mikko Immanen

Lilia Endter

Journal of the History of Ideas

Interview

Immanen reconsiders Adorno’s surprising intellectual debt to Oswald Spengler and Ludwig Klages, showing how their reactionary philosophies served as foils against which Adorno sharpened his thinking about reason, democracy, and history. Far from being simple influences, these encounters reveal a dialectical strategy of immanent critique: appropriating fragments of antithetical thought in order to expose its contradictions and redirect whatever insights it does offer toward emancipatory ends. The result, Immanen argues, is a radicalization of Adorno’s negative dialectics—an intellectual gamble that underscores both the fragility of democracy and the continuing dangers of authoritarianism in modernity.

“Adorno’s critique draws attention to the role of culture in the erosion of the conditions of democratic subjectivity. Adorno maintained that Spengler had observed, remarkably early on, how ‘centralized means of public communication’ can paralyze critical thinking and even lead, as in the Nazis’ euphemistically named ‘Kristallnacht’ violence of 1938, to ‘manipulated pogroms and “spontaneous” popular demonstrations. Our digitalized social media age may seemingly bear little resemblance to the interwar world of newspaper and radio, yet the danger remains that the newest technological advances can, and indeed already do, support the irrational ends of ‘mythic nationalism.’”

Afro-Arab Trajectories

Hisham Aidi

Souffles Monde

Essay

The Kenyan-Omani historian Ali Mazrui’s notion of “Afrabia” highlighted the deep historical, cultural, and political ties linking Africa and the Arab world, despite colonial efforts to draw stark boundaries across the Sahara. European racial science, from Kant and Hegel onward, entrenched the division between “North Africa” and “sub-Saharan Africa,” shaping colonial governance, academic categories, and even postcolonial international institutions. The essays in this issue of Souffles revisit slavery’s legacies, anticolonial solidarities, and the cross-pollination between Afro-Arab and pan-African thoughts, proposing an “Afro-Arab continuum” as a way to understand the intertwined histories and identities of the regions.

“If the boundary between Africa and the Arab world is a political artifact, the essays in this issue probe how ‘Afro-Arab’ is also a construct, and invariably a political response to colonial social engineering. It was European colonialists who first decided that the Red Sea and the Sahara were to be boundaries or divides. Decades ago Ali Mazrui traced the incongruous trajectory of the term Africa (Mazrui, 1986, p. 25), ‘Ifriqiya,’ once the Berber/Amazigh word for the northern coast of Africa, which would morph into ‘Africa’ and be adopted by Afrikaners at the southern tip of the continent, and then be embraced by African American thinkers who conceived of Africa from Cairo to the Cape; and yet, nowadays the term has come to connote Africa below the Sahara. The migration of the name reflects historic struggles within the continent and in the African diaspora over how to define and demarcate the African land mass. How Africa’s internal and external borders are drawn has political, social, and cultural repercussions, defining not only boundaries of citizenship and inclusion but also patterns of racial exclusion and domination.”

How Post-Materialism Fuelled the Rise of the Far Right

Joan C. Williams

LSE Inequalities

Essay

Williams dismantles the “post-materialism” narrative according to which class divisions have been displaced from politics: far-right parties have thrived not because class has disappeared, but because it has been recast as a cultural gulf between cosmopolitan elites and middle-status workers. Elites valorize self-development, mobility, and sophistication, while non-elites cling to self-discipline, rootedness, and institutions—family, religion, nation—which confer honor outside the capitalist hierarchy.

“What post-materialism captured was not the end of class, but a change in the way class conflict is expressed through politics. After elites centred post-materialist issues, a ‘representation gap’ arose, political scientists document: people who held progressive economic but culturally conservative values weren’t represented in mainstream parties in either Europe or the US. Far right parties stepped in to fill the gap. If mainstream parties want to lure back middle-status voters who are now voting with the far right, they need to embrace progressive economic policies, and learn how to build bridges between the divergent cultural values of elites and non-elites. That alone is the path past populism.”