Beyond Arendt and Gramsci

The Primacy of Politics

Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism has had a peculiar sort of influence. By sheer numbers, it is enormous: citations to the 1973 edition of her magnum opus show an increase from 71 in 1990 to 1,483 in 2025, according to Google Scholar. But most political commentators and public intellectuals approach the book as a reservoir of bons mots rather than a coherent argument. They pick and choose her insights about lying, the use of language, the slippage between formal and informal power in authoritarian states. In contrast, they ignore the central explanatory claims of the work. What are these and are they plausible?

Published in 1951, Origins analyzes two regimes: Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia. Arendt makes two fundamental arguments, one causal and the other classificatory. The causal argument is that the key precondition for the emergence of totalitarianism is the phenomenon of “social atomization,” itself the consequence of the emergence of a “classless society.”1 She makes the point in several passages in different registers. Thus the Nazis and the Communists “recruited their members from this mass of apparently indifferent people whom all other parties had given up as too apathetic or too stupid for their attention.”2 Their followers were masses who had grown “out of fragments of a highly atomized society whose competitive structure and concomitant loneliness of the individual had been held in check only through membership in a class.”3 World War I had begun the process of “the breakdown of classes and their transformation into masses.”4 Thus, social atomization attendant on classlessness is the basic cause of totalitarianism.

The classificatory argument is that Nazism and Stalinism, despite their apparent differences, were fundamentally similar types of regime in that both were based on the replacement of the party system with a “mass movement,” a shift in power from “the army to the police,” and the carrying out “of a foreign policy directed toward world domination.”5

Ideologically too the regimes were similar since they both justified themselves by the claim to instantiate a law of historical development: in the case of the Nazis, a Darwinian struggle for existence; and in the case of the Stalinists, a struggle to establish a socialist utopia. In both cases, mass terror was the instrument deployed to achieve this aim. As Arendt put the point:

Terror is the realization of the law of movement; its chief aim is to make it possible for the force of nature or history to race freely through mankind, unhindered by any spontaneous human action.6

Arendt is an intimidatingly erudite writer who ranged across the entire landscape of European thought and had a familiarity with multiple languages. It is, one suspects, precisely this erudition that has led some scholars to shy away from examining her key sociohistorical claims, as if engaging her work in this way were somehow gauche. But Origins is clearly meant to be an explanation of totalitarianism and needs to be discussed as such.7 The first question that should be posed is whether Weimar Germany or pre-Stalinist Russia were really “classless” societies? Obviously not, at least not if the term “class”—which Arendt never defines—is taken in its usual sense, of a group formed on the basis of ownership relations.

To take the German case first, one of the most fateful turning points on the road to National Socialism was the decision by the Social Democratic Party leadership to destroy the German Revolution by allying with the Freikorps, resulting in the disastrous preservation not only of the power of the Ruhr industrialists, but also the East Elbian landowners and bureaucrats.8 The nefarious consequences of this preservation of Germany’s class society for the health of Weimar democracy are obvious; the point with respect to Arendt’s argument is that it was not the creation of classless society, but rather the preservation of a particular form of class society that was one of the main preconditions of National Socialism.

It might seem initially that Arendt is on more solid ground in her analysis of Russia. But the country’s post-revolutionary experience creates problems for her account, which Arendt herself (to her great credit) recognizes. Unlike many other anti-communist intellectuals, Arendt had a lively sense of the sharp difference between Russia under Lenin and Russia under Stalin.9 Russia in the twenties under Lenin experienced the rapid development of an independent landholding peasantry, an organized working class, and “a new middle class which resulted from the NEP [New Economic Policy].”10 But this created an analytic problem for Arendt’s account: According to her theory, “classlessness” is one of the key preconditions of totalitarianism, and yet in its immediately pre-totalitarian period Russia experienced rapid class formation. Thus for Russia, she reversed the causality of her basic framework to suggest that classlessness and its correlate, atomization, were the result rather than the precondition of totalitarianism. But this then begs the question: Why did totalitarianism emerge in Russia if its main precondition was lacking?

These brief remarks are enough to show that the idea that a “classless society” was somehow a precondition for totalitarianism is flatly contradicted by the historical record of the two cases on which Arendt’s account rests. In Germany, it was precisely the preservation of a certain type of class society that caused Nazism, while in Russia, Stalinism was immediately preceded by class formation in the NEP period.

Perhaps, however, the process of social atomization could occur independently of the destruction of classes. If so, it should be possible to reconstruct Arendt’s account in a more Tocquevillian vein—as a theory of civil society or its absence, rather than of classes and their absence. But this too seems implausible. The evidence here is better for the fascist cases than it is for the Soviet Union, and it is worth pointing out that Arendt always excluded Italy from the category of “totalitarian regimes” because she felt the regime to be insufficiently radical (although the term “totalitarian” was an Italian invention). Nevertheless, in Italy and Germany civil society was highly developed prior to the authoritarian takeover. Cooperatives, churches, trade unions, political parties, and mutual aid societies had experienced a period of massive growth in both countries from 1870 on. So the idea that pre-fascist Germany or Italy were atomized mass societies is quite misleading given their robust civil societies. The same may also be true of Russia, as Arendt points out in her analysis of Lenin, whom she describes as having attempted to create an associational sphere from above by promoting professional organizations, emphasizing differences in nationalities, and deliberately fostering the development of intermediate organizations of all kinds between the state and the individuals.

And what did the totalitarians (be they Stalinists or Nazis) do with this organizational material—that is, civil society—once in power? They linked it to the regime’s purposes. Indeed, there is a backhanded acknowledgement of this in Arendt’s analysis of the organizational development of National Socialism, with its numerous professional associations for “teachers, lawyers, physicians, students, university professors, technicians, and workers.”11 The reason for this organizational proliferation is obvious: How else could these regimes mobilize the masses without these associations?

As a causal account, then, Origins is a non-starter: Neither classlessness nor social atomization explains totalitarianism. But perhaps this an unfair criterion with which to approach the book, which is better understood as offering a classification rather than an explanation. In that case the key issue is understanding totalitarianism itself. This is hardly an easier matter, for Arendt avoids explicitly conceptualizing the phenomenon except to insist repeatedly on its radical novelty.12 The closest she comes to a definition occurs at the very end of the book, where she identifies four elements: the transformation of “classes into masses, the emergence of a “mass movement”, the increased power of the police in relation to the military, and “a foreign policy openly directed toward world domination.”13

The first of these criteria is confusing as atomization or massification is originally presented as a cause of totalitarianism rather than an outcome (except, inconsistently, in the case of Russia). The second is difficult to pin down. How do we know the difference between a regime based on a mass movement, and one based on a single party? The third seems relatively clear but would presumably describe any police regime.

The problems with the fourth criterion are more telling, for the drive toward world domination describes a difference between Nazism and Stalinism rather than a similarity. Hitler was a geopolitical gambler willing to risk it all. Stalin, an advocate of Socialism in One Country, was extraordinarily cautious on the world stage, and indeed his rise to power was inextricably linked with the decline of the world revolutionary ambitions of the October Revolution and the exile and assassination of its greatest theorist, Leon Trotsky. So, in the Russian case, the consolidation of totalitarianism wasn’t defined by a drive toward “world domination” but by the renunciation of such a project.

Origins then is a paradoxical classic in the sense that both its fundamental explanatory and its classificatory project are largely duds. This is not to say that the book offers nothing. Arendt is at her best in describing the phenomenology of fascism; her description of the formlessness of the Nazi state with its satraps working to divine the “will of the leader” is acute.14 She is also very good on the attraction of conspiracy theories. As she puts it, “the mob really believed that truth was whatever respectable society had hypocritically passed over, or covered up with corruption.”15 But for an account of the most terrible regimes of the twentieth century, it is best to turn elsewhere.

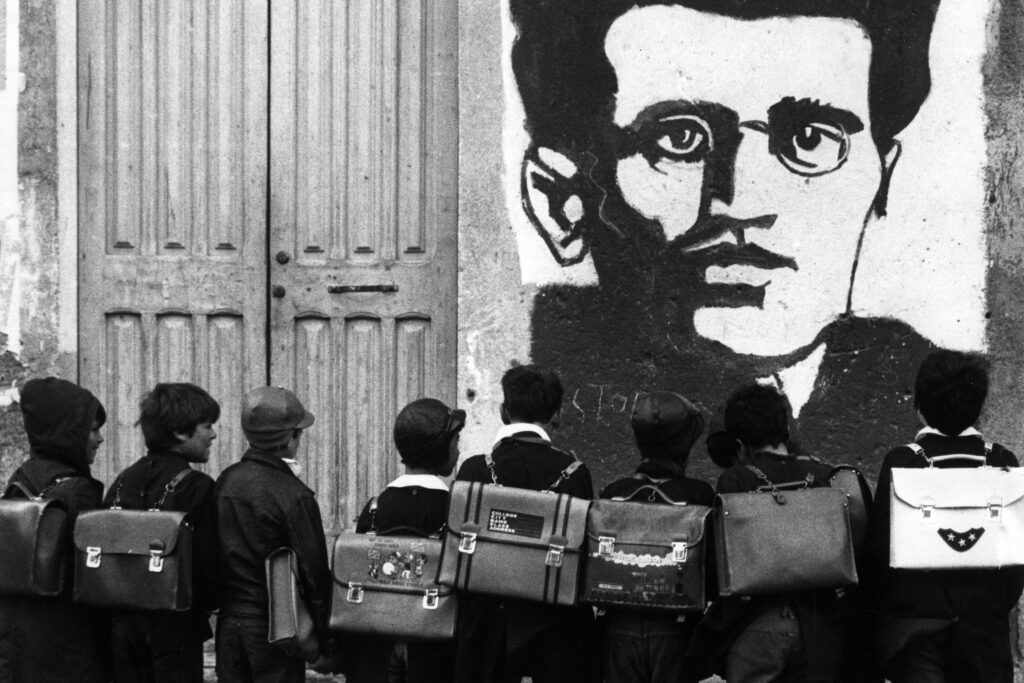

Gramsci

Antonio Gramsci, the enigmatic Sardinian, is a worthy alternative. He enjoys continuing relevance and a following even more assiduous than Arendt’s own. But their comparative claims have rarely been laid side by side. The reasons are not hard to find since the two thinkers were triply distanced from each other: by language, by political sympathy, and by generation. However, in some ways their concerns were similar, and even in some of their specific historical analyses there is a striking resemblance. Here is Arendt:16

The October Revolution’s amazingly easy victory occurred in a country where a despotic and centralized bureaucracy governed a structureless mass population which neither the remnants of the rural feudal orders nor the weak, nascent urban capitalist classes had organized.

Gramsci’s analysis was almost identical:17

In Russia the state was everything and civil society was primordial and gelatinous; in the West there was a proper relationship between the state and civil society, and when the state trembled the sturdy structure of civil society was at once revealed.

But it is precisely here, where they are closest, that the differences in their analyses are clearest. For Gramsci did not see the interwar period in the West as one of atomization and isolation: It was characterized by a crisis generated by the massive development of civil society, not by its collapse, let alone the disappearance of classes. From Gramsci’s perspective, the problem was that the weak liberalisms of nineteenth-century Europe were suddenly faced with highly organized and politicized populations whose democratic demands could not be channeled into the representative institutions as they then existed. Although Gramsci did not use the term “totalitarianism” in Arendt’s sense, the fundamental cause of fascism was exactly opposite to that proposed by The Origins of Totalitarianism.

The Current Conjuncture

Where does all this leave us today? What to do with Arendt and Gramsci, with atomization, civil society, and totalitarianism?

From the perspective of Arendtians, and the whole literature on mass society that her work spawned, the situation is contradictory. The fundamental preconditions of totalitarianism seem present: isolation, atomization, and loneliness. Many have sought to link these to the phenomenon of Trumpism. But whatever dangers MAGA might pose, and these are very serious, not even the most convinced maximalist could describe it as a totalitarian movement in the Arendtian sense. In the first place it lacks an overall theory of history, and who could describe the brutal, but erratic and amateurish, foreign policy emanating from the White House as a drive to world domination? Thus, we seem to have the cause (social atomization) without the effect (totalitarian domination).

What about from the Gramscian perspective? Here the problem is the opposite. Although there has been a recent uptick in political participation, are the civil societies in the West, and particularly in the United States, nearly so mobilized as they were in the interwar period? It is unlikely. And yet there does seem to be a legitimation crisis of Western democracy (a “crisis of hegemony,” Gramsci would have said), of which Trump is one, but not the only, expression. Here there is the effect without the cause.

Perhaps the best way to grasp what is happening is to focus on the problem of politics. The real issue in the West today is not a threatened revolutionary rupture producing as its opposite a counter-revolutionary response, but rather an etiolation of the links between the realm of private and associational life and the realm of politics. This split created a rupture between political representatives and the groups that they were supposed to be representing: a fracture that was clearest in the Republican Party from 2015 on but that had its counterpart in the revolt of the Democratic Party’s new left. What is occurring now is an incipient restructuring of these links on the ground of a terrain that is still in the process of formation. The point is not about being “for” or “against” civil society, but rather about who will control the process of its political articulation.

It is particularly important to understand that it is not the case that MAGA wishes to destroy civil society as a realm of associations and interest groups (which is another obvious way it cannot be understood as a totalitarian movement in the sense of Origins). Rather, MAGA seeks to colonize this realm: It does not discourage civic engagement; it tries to promote its own forms of it.

Examples of this abound: J.D. Vance’s exhortation on Charlie Kirk’s podcast to “get involved, get involved, get involved” after explaining that “civil society is not just something that flows from the government, it flows from all of us” is one obvious instance. So is the recent effort by Ryan Walters, the former superintendent of Oklahoma’s public schools, to encourage the establishment of a Turning Point USA chapter in every high school and college in the state.

This is a struggle for hegemony fought on the terrain of civil society, what Gramsci would have called a war of position, not a struggle for or against civil society as a mythical realm of pre-political consensus and practical problem solving.

The left in the US stands at a severe disadvantage in this combat. Its intellectuals, largely cordoned off in academia, and to a lesser extent in the world of the non-profits, have little access to political parties or social movements. They are therefore isolated from the political and social forces necessary for joining the fight.

But here lies an irony about which Trumpists are blissfully unaware. Far from exercising much cultural influence, leftist and progressive intellectuals have for decades been a privileged but largely irrelevant clerisy within the university/NGO complex, where they have formed what Gramsci would have called a traditional intelligentsia speaking to itself in its own rather arcane language. It is not outside the realm of possibility that the Trump administration’s attempted destruction of the cordon sanitaire that insulates these intellectuals from the world of politics might create the conditions through which they could establish a more intimate link to politics. In that way Trump would have had a hand in the creation of a new modern prince adapted to the age of social media, virality, and artificial intelligence. MAGA would reveal itself as the midwife of the very thing it most fears.

And what of Origins? Perhaps the very thing that has brought the text such massive notoriety—its extreme facility in describing the feeling of authoritarianism—is what makes it an overly blunt, if not entirely misleading, instrument for understanding the present. In order to orient ourselves we need explanation more than phenomenology. And for that it is better to turn to the greatest political thinker of the twentieth century rather than to the metaphysician of total domination.

Dylan Riley is Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. He studies capitalism, socialism, democracy, authoritarianism, and knowledge regimes in comparative and historical perspective, and is the author or co-author of six books and numerous articles.

- Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (Penguin Classics, 2017 [1951]), 403. Arendt writes that “totalitarian movements aim at and succeed in organizing masses not classes.” More generally, see the long chapter entitled “A Classless Society”, 399–445. ↩︎

- Origins, 407–08. ↩︎

- Origins, 419. ↩︎

- Origins, 431. ↩︎

- Origins, 604. ↩︎

- Origins, 610. ↩︎

- Some Arendt commentators have sought to protect her theory by claiming that it was never intended to be a causal account. For example, Tatjana Tömmel and Maurizio Passerin d’Entreves who write in “Hannah Arendt,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2025), 8, “Arendt did not want to provide a causal explanation for totalitarianism, but rather a historical investigation of the elements that ‘crystallized into totalitarianism.’” But causal claims are littered throughout Origins. For example, Arendt claims on page 417 that, “To change Lenin’s revolutionary dictatorship into a full totalitarian rule, Stalin first had to create artificially that atomized society which had been prepared for the Nazis in Germany by historical developments.” ↩︎

- Hans Mommsen, The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy, (University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 46: “…the revolutionary movements had failed to bring about any changes in the distribution of economic power. In point of fact, the unions had already lost so much ground that little remained except to fight for a compensatory social policy. Even less spectacular were the achievements of the revolutionary movement in the nonindustrial sector. In its concern for maintaining a continuous supply of food, the MSPD ( Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany) had refrained from demanding far-reaching changes in the structure of German agriculture and settled for promises of cooperation from Germany’s landowning classes. The principal casualty of this tactic was land reform in East Elbia.” ↩︎

- Origins, 417–18. ↩︎

- Origins, 417. ↩︎

- OT, 485. ↩︎

- The Arendt scholar Peter Baehr’s “Identifying the Unprecedented: Hannah Arendt, Totalitarianism, and the Critique of Sociology,” American Sociological Review 67, no. 6 (2002): 811 offers the following encapsulation: “Totalitarianism is a term… that describes a type of regime that, no longer satisfied with the limited aims of classical despotisms and dictatorships, demands continual mobilization of its subjects and never allows the society to settle down into a durable, hierarchical order.” Strikingly he offers no textual reference for this formulation. ↩︎

- Origins, 604. ↩︎

- Origins, 522–24. ↩︎

- Origins, 459. ↩︎

- Origins, 417. ↩︎

- Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks (International Publishers, 1992 [1971]): 237–38. ↩︎