Socialism After AI

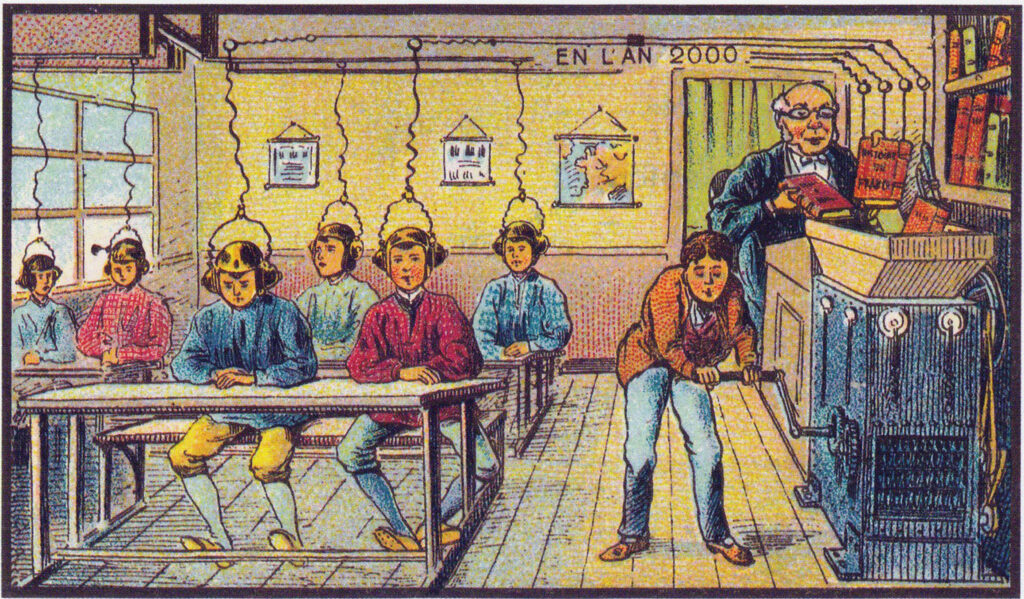

Artificial intelligence has produced a rare kind of popular curiosity. Not only among investors and founders, but among people who open a browser, type a question, and feel—however inaccurately—that something on the other side is thinking with them. That phenomenology matters. Whatever we think about hype, hallucinations, or OpenAI’s capitalization table, AI arrives as a technology whose uses are discovered after deployment, whose boundaries are porous, and whose side‑effects appear in places nobody designed for. “Generative” is not just a marketing word; it names a genuine instability.

For socialists, this instability poses a specific challenge. And their reflexes are familiar: Regulate platforms, tax windfalls, nationalize leading firms, plug their models into a planning apparatus. But if socialism is to be more than capitalism with nicer dashboards—if it really is a project of collectively remaking material life, not just of redistributing its outputs—it has to answer a harder question: Can it offer a better way of living with this technology than capitalism does? Can it deliver a distinct form of life worth wanting rather than just a fairer share of what capital has already made?

Once you pose the problem like this, something embarrassing appears. For a tradition obsessed with maximizing productive forces, socialism has been remarkably quick to bracket some of them from politics. It treats technology as a neutral kit to be dropped into better institutions once these exist. Take railways, nuclear plants, or language models: If capitalism misuses them, socialism promises to finally aim them at the common good. The real question, however, is whether even the most ambitious recent socialist theory escapes this limitation—or whether it reproduces neutrality at a higher level of sophistication.

I.

Aaron Benanav’s proposal for a “multi‑criterial economy,” developed in two lengthy essays in New Left Review, offers a test case. His diagnosis is that both capitalism and classic state socialism are organized around “single-criterion” optimization: capitalism around profit and state socialism around gross output. That worked, brutally, as long as rising GDP could serve as justification. In an era of stagnation, ecological breakdown, and care crises, it no longer does, at least not in the Global North (sadly, the peculiarities of the Global South do not much figure in Benanav’s analysis).

Benanav wants an economic democracy that takes multiple, incommensurable goals seriously from the start. Ecological sustainability, work quality, free time, and care are treated as distinct goods that cannot be crushed into a single index. The balance between them is composed and recomposed through explicit political choices, rather than discovered by a market or a central algorithm.

To this end he proposes a dual monetary system. Individuals would receive non‑tradeable credits for personal consumption and a basic income; firms and public bodies would transact in “points” that could only be used for investment and production. Investment would no longer come from retained profits, but from democratically governed “Investment Boards” that would allocate points across projects according to multiple criteria.

In this model, coordination is handled by sectoral and regional councils of workers, consumers, community representatives, and technical experts. They are aided by a “Data Matrix,” an open, democratically governed statistical and modeling system that tracks flows, maps ecological and social limits, and makes trade‑offs visible: If we decarbonize at such a pace, build so many homes, and shorten the working week by this much, here is what follows. Markets persist but lose their profit logic. Firms cannot hoard earnings or decide the long‑term direction of the economy; they compete over performance on democratically chosen metrics, not over returns to private shareholders. “Technical Associations” organize labor, training, and expertise across sectors.

Benanav insists that values are not fixed. Drawing on the Austrian polymath Otto Neurath, the American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey, and others, he argues that priorities evolve through conflict, learning, and experience. Plans must be revised, criteria adjusted, and institutions rebuilt in light of what happens. Socialism, in his picture, is inherently experimental. He even carves out a publicly funded “Free Sector” for artists, movements, and associations to explore new forms of life and value, feeding their innovations back into the official criteria.

As a vision of post‑capitalist institutions, this is unusually detailed. But it rests on an assumption: that socialism’s historical failures were failures of procedure—too little democracy, too crude a criterion. What if the problem runs deeper? Point an unstable technology like AI at Benanav’s carefully drawn architecture and cracks appear that no amount of democratic procedure can seal.

II.

The difficulty does not reside in any particular blueprint; it’s structural. Socialist thought has organized itself around a series of dichotomies—productive forces versus relations of production, base versus superstructure, means versus ends—and in each case it has placed technology on the neutral, instrumental side: with the conveyor belt, the nuclear plant, the language model. Under capitalism, the wrong class bends this machinery to its purposes; under socialism, the same machinery gets redirected to better goals.

A rich critical tradition, much of it in socialism-adjacent fields, rejects this neutrality thesis. Marcuse showed technology embedding domination, not merely serving it. Harry Braverman (namechecked by Benanav) showed how Taylorist machinery de-skills workers by design. David Noble went further, demonstrating that automation itself was not technically determined: When multiple paths existed, capital systematically chose those that transferred knowledge from the shop floor to management, even at the cost of efficiency. From a different direction, Cornelius Castoriadis argued that capitalist technology materializes a capitalist imaginary—unlimited expansion, rational mastery, quantification—and cannot simply be repurposed (at least not until a different imaginary is in place). Andrew Feenberg synthesized several of these insights by describing technology as “ambivalent,” suspended between trajectories that democratic intervention can alter.

But these insights almost inevitably cash out as theories of workplace restructuring or democratic procedure—how to reorganize labor, how to open technical decisions to participation. They rarely transform the macro-institutional imagination that would ground socialism as a wholescale and systemic—rather than a merely ameliorist and procedural—alternative to capitalism. When socialists design whole economies, technology reverts to hardware that a different class will use better. Benanav, for all his sophistication, works inside this template: The “Demos” and the Investment Boards determine criteria; firms and Technical Associations implement them; technologies are instruments.

AI doesn’t quite fit this template. It makes postponing the “question concerning technology”—to use Heidegger’s phrase in a register he wouldn’t have recognized—harder to get away with. A large language model (LLM) trained on cheaply scraped text, tuned for fluent plausibility, and monetized through metered access is not simply statistics at scale. It is the material expression of a particular world: venture capital timelines, advertising markets, data extraction, intellectual‑property arbitrage. The conversational interface that makes the model feel like an interlocutor rather than a library was a product decision designed to encourage specific forms of use and attachment. The safety layers encode a particular sense of what is sayable, polite, or risky.

A system like that does not simply respond to existing social relations; it crystallizes them and feeds them back presenting them as common sense. Even the prevailing definition of AI—as closed, general‑purpose models in distant data centers, accessed through chat—condenses a series of capitalist choices about scale, ownership, opacity, and user dependence.

Now imagine a future in which a multi‑criterial Investment Board, under pressure to avoid bias and misinformation, mandates that AI systems be fair according to agreed metrics, respect privacy, minimize energy use, and promote well‑being. Call this woke AI by democratic mandate—an infrastructure whose outputs are correct, diverse, and balanced. Yet it still feels like it was designed over our heads. The ham‑fisted “fairness” tweaks to image generators that tried to hard‑code diversity have given us a foretaste. They were mocked not because diversity is a bad aim, but because it appeared as a static parameter to be satisfied rather than as a transformation emerging from changed social practice. A multi‑criterial AI governed by Investment Boards risks repeating that pattern by treating values as checkboxes rather than as meanings worked out in the messy process of using and reshaping the tools themselves.

This is where Benanav’s clean separation between an economy that executes and spheres that decide becomes costly. In his schema, values originate outside production—in democratic deliberation or the Free Sector—and are then applied to technology through Investment Boards and oversight bodies. But AI exposes a circularity that no amount of democratic procedure can resolve: The values we would use to govern these systems are themselves being formed through our encounters with those (ever fluid) systems. Nobody voted to make chatting to bots part of everyday life. Nobody deliberated in advance what that would mean for authorship, pedagogy, or intimacy when machines began mimicking human prose. And judgments about all that are being made now—inside product teams, terms of service, and the improvisations of millions of users, not in assemblies that could later apply them to a waiting technology.

The familiar solutions do not escape this circle. More workplace democracy, more participatory technology assessment, more inclusive governance boards—all presuppose that we already know what we value and need only broader input on trade-offs. But when the technology in question reshapes the very capacities, self-concepts, and desires of those who use it, there is no stable vantage point from which to govern. We are asking, “By what criteria should we shape this thing?” even as the thing itself is shaping the beings who must answer this question. This is not a problem that better procedures can fix. It is a structural condition that any socialism serious about technology will have to inhabit rather than resolve.

III.

Benanav’s multi-criterial model, for all its plurality, still rests on a single, higher-order criterion: that decisions must pass through the right democratic procedures. Beneath this lies a familiar Weberian image of modernity as a set of differentiated spheres—the economy here, science there, politics somewhere else—retouched by a bit of Habermas adding that we can coordinate across them through communicative discourse.

Socialists have rarely questioned this image. Fredric Jameson, in his celebrated account of postmodernism, came close. Writing in the 1980s, he observed that late capitalism had already de-differentiated the spheres: high culture and low culture bleed into each other, and commodity logic saturates everything from exhibitions to molecular gastronomy. Jameson spent decades mapping such de-differentiation across culture—cinema, literature, architecture—but left the economy strangely untouched. Yet if late capitalism really scrambles the boundaries between domains—and in a way that Jameson didn’t entirely disapprove of—why should socialist planning operate as if those boundaries still hold?

For Jameson, play, impurity, and pastiche were everywhere—except in how socialists should think about that nontrivial part of life (including technology) that lies beyond high and low culture. In a 1990 essay, he even praised the Chicago economist Gary Becker’s “admirably totalizing approach” to viewing all human behavior as economic activity and confessed to sharing “virtually everything” with the neoliberals—“save the essentials.” What they shared, he argued, is a conviction that politics is simply “the care and feeding of the economic apparatus”; they disagreed only about which apparatus. For Jameson, this turned both camps into allies against the vacuity of liberal political philosophy.

But this symmetry is Jameson’s projection. He imagines the neoliberals as Beckerian administrators and the market as a control mechanism, “a policeman meant to keep Stalin from the gates.” What neither he nor many of his fellow Marxists entertain is a politics oriented toward discovering the plurality of meanings that technologies, practices, and social forms might attain as they germinate, hybridize, and mutate—not only in the novels of Balzac or the buildings of Koolhaas (terrain the Jamesonian tradition has mined to exhaustion), but in the very course of production itself. On this score, as we will see, the actual neoliberals—of the Silicon Valley kind, not the Chicago kind—are less Weberian than their Marxist critics. They are not administrators but worldmakers; they feed off the cross-contamination of domains and monetize the impurity Jameson can only diagnose.

But what if socialist soul-searching were to begin elsewhere—neither restoring differentiated spheres like Benanav, nor collapsing them all into the economic realm like Jameson, but abandoning the premise that politics, expertise, creativity, and technology ever belonged in distinct boxes?

With AI, such separations are especially hard to defend. This technology is simultaneously a tool, a medium, a cultural form, an epistemic instrument, and a site of value formation—much as Raymond Williams once described television, but with far less stability. You cannot slot it into a single sphere and manage it from the outside.

So the question shifts. Instead of asking, “How do we best coordinate this technological ensemble under multiple democratic criteria?”, we might ask, “What kinds of institutions make it possible to systematically explore different technological ensembles and different ways of living with them?” The problem is less optimal coordination than organized experimentation.

That implies ecologies of experiment, not a single Data Matrix feeding a single set of Investment Boards. Imagine, alongside the corporate giants, a dense layer of municipal, cooperative, and movement‑based AI projects, each with their own priorities. A city government might maintain open models trained on public documents and local knowledge, integrated into schools, clinics, and housing offices under rules set by residents. A network of artists and archivists might build models specialized in endangered languages and regional cultures, fine‑tuned to materials their communities actually care about.

The point is not that these examples are the answer, but that a socialism worthy of AI would institutionalize the capacity to try such arrangements, inhabit them, and modify or abandon them—and at scale, with real resources. This kind of socialism would treat AI as plastic enough to accommodate uses, values, and social forms that emerge only as it is deployed. It would see AI less as an object to govern (or govern with) and more as a field of collective discovery and self-transformation.

Seen this way, technology is not a surface onto which we project pre‑existing values; it is one of the main sites where values are formed. People working with particular tools develop new skills and sensitivities, learning that some uses feel like care and others like surveillance, that some interfaces invite pedagogy and others encourage cheating—all while reconsidering what care, surveillance, pedagogy, and cheating actually mean. Those judgments cannot be produced in advance by abstract deliberation; they emerge in practice.

Benanav’s architecture nods to this by emphasizing that values evolve and by funding a Free Sector of “value creators.” But structurally, it still assumes a one‑way flow: The Demos and the Free Sector generate priorities, and Investment Boards and economic institutions then implement them. What is missing is an account of how values emerge from within production and design themselves—how, around a technology like AI, the distinction between “functional economy” and “free creativity” becomes porous to the point of breakdown.

Gillian Rose, whose early work excavated how post-Kantian thought severed Hegel’s “ethical life” into lifeless dualisms—values versus facts, norms versus institutions—later named this terrain “the broken middle”: the zone where means and ends, morality and legality, are worked out in particular contexts rather than applied from outside. What she called “the holy middle” was the fantasy of escaping this brokenness into purified harmony, whether procedural or redemptive. Around AI, that zone is politically decisive. Treating technology as a purely instrumental sphere that politics steers from outside is not just naïve; it blinds us to where power now sits.

IV.

At this point a reasonable worry appears: Would anything else not just mean chaos? Isn’t socialism meant to free us from the churn of capitalist innovation, with its gadgets and planned obsolescence?

The answer depends on the kind of impurity we embrace. There is the technocratic violence of top‑down modernization, which bulldozes existing ways of life and calls the rubble “progress.” And there is what the Ecuadorian‑Mexican philosopher Bolívar Echeverría calls a “baroque” ethos: Accept that modernity is here to stay but refuse to live it in the pure, hygienic form that capital prefers—by bending norms, obeying without quite complying, eating the code, and spitting out something else.

Capitalism has its own baroque, of course. The Silicon Valley entrepreneur—unlike the Beckerian administrator Jameson imagined—creates new values by building new worlds and accelerating the cross-contamination of technology, culture, and desire. But this is baroque in the service of accumulation, impurity harnessed toward a single trajectory.

Echeverría’s point cuts deeper. Central to his argument is a rereading of a core Marxist idea: use‑value. Every technology, he insists, contains an infinity of possible actualizations—the plural trajectories it might take, the various forms of life it might enable. Capitalism does not eliminate this plurality; it re-functionalizes it, steering development toward the singular path to valorization. The suppressed possibilities do not vanish; they persist as latent potentials, available for rediscovery under different social conditions.

Applied to AI, this means the task is not simply to regulate or redistribute technologies whose basic shape is taken as given, but to explore the trajectories that capitalist development has foreclosed. What might language models become if they were not designed around monetization imperatives and corporate risk management? What forms of creativity, memory, or collaboration might they enable if training data were curated by communities rather than scraped at scale and if interfaces invited inquiry rather than attachment? We cannot know in advance. The baroque strategy is to treat every encounter with these systems as a test of whether other actualizations remain possible. To try, fail, and try again.

Benanav’s framework pulls in the opposite direction. Following Robert Brenner, he treats capitalist dynamism as real—firms innovating through competition, the market as a genuine discovery process. But this misreads the sources of capitalism’s power. Take Google: Its rise is inseparable from American control over communications infrastructure, the political project of internet liberalization, and a security order that has routed global traffic through US systems. Capitalist innovation is entangled with state power, imperial hierarchies, and legal engineering. Mistaking this for spontaneous market discovery risks preserving in socialism what was never the true engine of technical change in capitalism.

Benanav hopes that multi‑criterial composition—the continuous re‑weighing of efficiency, ecology, care, free time—would generate the kind of dynamic responsiveness that older forms of socialism lacked. But such responsiveness risks being administrative rather than creative: It steers (democratically) rather than invents. And here a deeper problem surfaces. Benanav offers socialism as an answer to a question that capitalism never poses: How should we democratically balance competing values? But he never answers the question that capitalism does pose: Where, apart from assembly halls and concert venues, does creativity come from? What drives the cross-contamination of domains, the invention of new desires and capacities, and the fusing of imagination and matter? Anyone who has listened to Steve Jobs, Peter Thiel, or Elon Musk knows that neoliberalism is not the Beckerian administration of a market apparatus that Jameson imagined. It is a project of worldmaking. And its pitch is clear: The market is the vehicle through which human capacities are enlarged, as consumers discover new tastes and entrepreneurs build new worlds.

If socialism is to answer capitalism on its own terrain, it needs a rival worldmaking vehicle—not simply the democratized administration of an economy whose creativity happens elsewhere. This is where AI matters. The wager of a socialist AI society would be that the generative functions neoliberals assign to the market—experimentation, discovery, the power to make worlds out of ideas—can now pass through a different medium. Call this socialist baroque: collectively governed AI systems embedded in workplaces, schools, clinics, and cooperatives that enable the same worldmaking the entrepreneur claims for capital but without the accumulation imperative that distorts and forecloses the paths not taken.

The driving imperative would not be “growth” measured as ever more commodities, but the enlargement of what people are actually able to do and be, individually and collectively.

On that view, AI would be judged by whether it opens new spaces of competence, understanding, and cooperation, and for whom. A tool that lets teachers and students work in their own dialects, interrogate history from their vantage points, and share and refine local knowledge would score highly. One that smooths people into passive consumers of autogenerated sludge, or concentrates interpretive power in a handful of machine‑learning priests, would score poorly, whatever its efficiency.

Whether such a capacity‑expanding socialism—aimed at the maximization of creative forces, not just productive ones—is possible remains an open question. What matters here is that frameworks like Benanav’s barely let us pose it. They have detailed rules for balancing criteria once we have them, but they say much less about where those criteria come from, how they change, and how technology itself participates in their emergence. Even as they recognize that needs are historically shaped, they forget that abilities are too.

V.

AI matters less because it is the most important technology, or a guaranteed route to emancipation or disaster, than because it exposes faults in socialist thinking that were easier to ignore when the paradigm was the steam engine or the assembly line. Those older machines could at least be described, however incorrectly, as relatively stable tools whose uses were largely fixed at the moment of design. With AI, the tool itself keeps changing—and right in front of us. Its uses are discovered in practice. Its boundaries blur into culture, media, cognition, affect. Under those conditions, a socialism that treats technology as a finished script and politics as the art of directing it will always arrive too late.

A socialism worthy of AI cannot retreat to a clean division of labor in which politics decides and technology provides. It has to acknowledge technology as a primary site of collective self‑formation. The point is not to abandon the democratic composition of criteria, nor to romanticize chaos. It is to build institutions that treat collective existence as a field of struggle and experiment—one where new values, new abilities, and new ways of living are constantly taking shape.

That means accepting impurity not only as a design principle but as an existential condition. Instead of imagining a neatly functional economy supplemented by a cordoned‑off Free Sector, we need porous arrangements in which experiments circulate between spheres, sometimes colliding with official metrics, sometimes remaking them. Institutions would not only balance criteria; they would leave space for unruly projects that do not yet fit any recognized metric and that may never do so.

The unresolved question, then, is not whether socialism can socialize AI while keeping its underlying machinery intact. It is whether socialism can become a project of worldmaking—concerned not only with who owns the machines, but with what they let people do and become. A socialism that merely redistributes the fruits of capitalist technologies will always chase a world made elsewhere. One that takes seriously the eerily generative but unstable power of AI might help make a different world—and a different people—from the start.

Evgeny Morozov is the founder and publisher of The Syllabus. He is the author of The Net Delusion and To Save Everything, Click Here.