Where a Hundred Analogies Bloom

The Perils of Comparing Trump to Mao

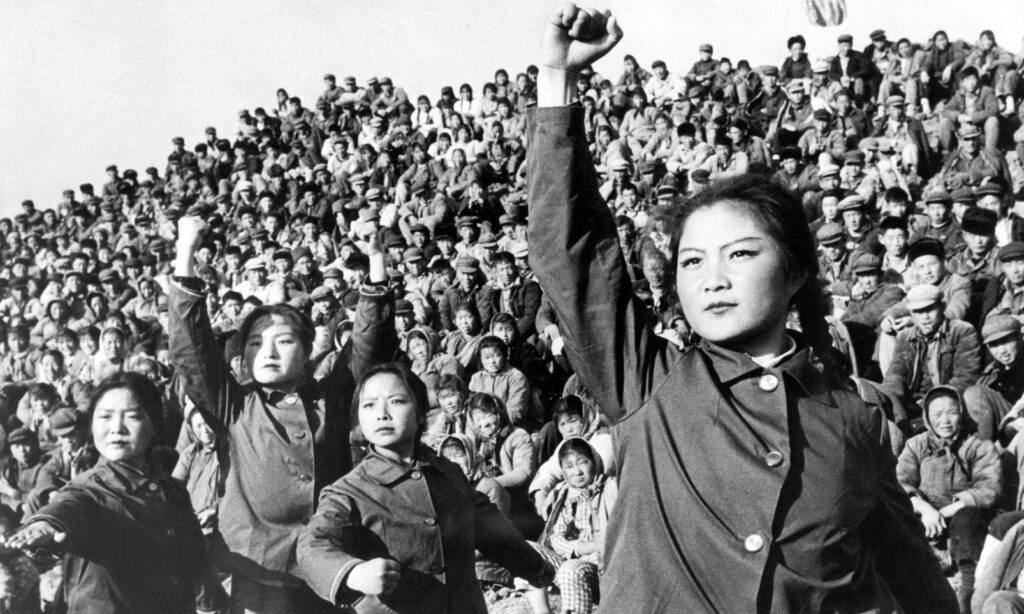

Current political discourse is haunted by a specter—the specter of Maoism. When conventional politics starts to spin away from the mainstream and arouses the passions of the people, Mao often is invoked. Commentators routinely analogize Trump to him, calling the two men kindred spirits in “chaos” who “would have got on well.” The China expert Orville Schell has written that the Chairman “must be looking down from his Marxist-Leninist heaven with a smile.”

But would Mao really have celebrated anything beyond disorder for the US empire?

Such easy analogies are not only incorrect; worse, they damage our capacity for critical thinking and political action. Relying on them inhibits imagining a democratic politics beyond liberal democracy.

During periods of uncertainty, historical analogies can convey familiarity. But as they do, they distract from what is new in the present. Trump has been compared not only to Mao, but also to Hitler—as well as to contemporaries such as Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, and the dictators of so-called banana republics. As we travel in that time machine, one moment we are in the kinetic interwar years; in the next, we glaciate in a new Cold War. Analogies seem to reassure us that we have been there before. In fact, they only confuse any real sense of where we are now.

Portraits of bad men—master manipulators with a sociopathic disregard for the havoc they wreak on their nations, peoples, and economies—may be accurate characterizations, but they say little about sociopolitical dynamics, which are larger than any personality. They do not make up for proper political analysis. When a leader’s actions are presented out of context, their only imaginable purpose appears to be the consolidation of power—power without politics.

Yet historical analogies themselves are rhetorical devices; they too are tellers and makers of tales, and they create political claims. They implicitly ask us to see the world in a certain way—usually from the perspective of the status quo, from which alternative modes of politics are passed over or pathologized. To compare Trump to Mao and the US culture wars to the Cultural Revolution is to reduce entirely different political visions to reified personalities. It is to reduce the collective dreams of the Chinese Revolution—of a world free of capitalist exploitation and imperialist domination—to the monologues of a mad dictator. And it is to focus on Trump alone, instead of the conditions from which he emerged.

Mad Men

Both Mao and Trump have been called erratic, vindictive, and paranoid, and have been said to have a ruthless “will to autocracy.” The sinologist Geremie Barmé, who studied in China during the waning years of Maoism, has observed that both leaders suffer from insomnia and late-night decision-making. If only Mao had taken melatonin, the implication seems to be, the Cultural Revolution might have been avoided.

The China watchers Orville Schell and David Lampton separately have suggested that Mao’s and Trump’s “penchant for disorder,” as Schell puts it, may have deep psychological roots in their childhoods because the two leaders were bullied by their fathers. Both Schell and Barmé note Mao’s self-identification with the Monkey King (孙悟空) from the sixteenth-century novel Journey to the West: The creature, a trickster spirit with supernatural powers in a monkey’s body, rebelled against authority and celestial bureaucracy, reveling in “great disorder under heaven” (大闹天宫)—a phrase that Mao also used to refer to the Cultural Revolution. According to the Guardian columnist Tania Branigan, “Mao relished disruption” and Trump seems to be enjoying chaos. “Disruption” is the shibboleth of Silicon Valley tech-bros; “creative destruction” is said to be the beating heart of capitalism. And yet a shared fondness for disruption says nothing of the different orders born from disorder.

Much like Branigan characterizes Mao as “a vengeful, anarchic force,” Paul Krugman argues that Trump, like Mao, is driven by “retribution” without purpose. “It’s not a considered political strategy, with a clear end goal. It’s a visceral response from people who… are addicted to revenge. If you want a model for what’s happening to America, think of Mao’s Cultural Revolution.” Anticipating the observation that both leaders espoused radically different political ideologies, Krugman invokes the “horseshoe theory, which says that the extreme left and the extreme right are more like each other than either is like the political center.” Leaving the center, one descends into a realm of “visceral urges,” populated by revenge junkies. Schell, for his part, argues that both Mao and Trump respond to an “animal instinct,” for “being unpredictable to the point of madness.” According to his grab-bag of armchair zoology and Freudianism, they failed to develop a human organ for political vision.

The prejudices that analogize Mao and Trump extend to writing off their followers. In an essay for the New Yorker, Jiayang Fan claimed that Mao and Trump are “bombastic demagogues” skilled in the art of manipulating the masses. For Branigan, they relied on “dramatic rhetoric to whip up the mob and destroy institutions.” China’s Red Guards and Trump’s MAGA supporters alike must be brainwashed dupes, all seduced by the pulsating color of red. Branigan does not mince words: “Trump’s uncanny ability to channel the public’s id felt discomfortingly familiar.”

But such positions—the antipolitics of analogy—leave important questions unasked, let alone unanswered. Why did Mao’s call to rebel against bureaucracy and hierarchy resonate with Chinese people in the late 1960s? Why does Trump appeal to so many Americans? Heterogenous constituencies support him, for various reasons. And there are heated debates among China scholars over what explains both following and factionalism under the Cultural Revolution. Simply condemning populism as the new opium of the masses drowns out essential contexts, political beliefs, and ambivalent emotions.

In these accounts, ordinary people become an instrument of revenge, the plaything of dictatorial caprice. Lampton has noted how “both Mao and Trump mobilized popular resentments of the masses to attack their opponents.” Fan identified the cornerstone of Mao’s political philosophy in the division between “the people” and “the enemy.” During Trump’s first term, she argued, “The ease with which Trump erected and proselytized this divide speaks to what the Chairman would have labelled a ripeness for class struggle.” This is an excellent point, but she retreats from it too quickly, to regain the comforting ground of analogy.

What if the US is ripe for class struggle? And what if Trump is a way to contain it? Trump’s skill at tapping “proletarian resentment” may allow him to channel it away from class struggle toward anti-immigrant chauvinism and nationalist bellicosity. But instead of staying with this complexity, Fan focuses on how Trump shares “Mao’s knack for polemical excess and xenophobic paranoia.” Never mind that China’s revolutionary political commitments then tempered the emergence of national and Han-centric chauvinism that is unfolding in China today. Or that Trump’s sentimental appeals to the white American working class have paved the way for a new gilded age of oligarchic rule, unrestrained capital accumulation, and class warfare from above.

Instead of regarding Mao and Trump as ventriloquists of popular sentiment, what if we considered, as the historian Aminda Smith argues, that “Trumpism, like Maoism, empowers people to speak”? What then might we learn from listening to people who have been marginalized, ridiculed, and excluded from political speech? During the Cultural Revolution, some people challenged Communist Party hierarchy, cadre privilege (特权), and managerial power. Others vented pent-up anger over unfair class labels and fresh memories of injustice, blurring the line between revolutionary violence and vengeance. At times, the momentum exceeded and threatened to slip away from Mao’s control. In the US, people voted for Trump because he appeared to be listening to and translating their desires and their fears into the idiom of state power.

And yet the fact that both Mao and Trump speak to people’s emotions does not mean they are saying the same thing. Combatting the appeal of Trumpism requires addressing its root causes and fashioning alternative political narratives that mobilize people’s desire to collectively transform their living conditions. Maoism was one such alternative; there are numerous others. Michael Dutton, a political theorist and China scholar, defines Maoism as a machinery for channeling affective intensities into a master narrative of class struggle. It would not make sense to copy outdated Maoist tactics to compete with the Alt-Right, but studying their successes and learning from their mistakes does—even if that means trespassing liberalism’s prohibition against entering the terra incognita of political emotion and mass politics.

Dismantling the Deep State

As Lampton suggests, the desire to “crush bureaucracy” is not only a matter of personal “whim”; it is also about political vision and re-configuring power relations. A touch of historical memory is instructive here. In an interview in 2013, Steve Bannon, the architect of Trump’s 2016 campaign, claimed: “I’m a Leninist. … Lenin wanted to destroy the state, and that’s my goal, too. I want to bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today’s establishment.” Even before the hundred Mao/Trump analogies bloomed, some analysts had compared Bannon’s campaign strategies to those of Lenin—“the godfather of post-truth politics,” according to Victor Sebestyen in the Guardian—and had tagged Trump as his heir.

Yet no one asked this simple question: Are Lenin’s and Bannon’s visions for post-state existence the same? Whereas Lenin argued in State and Revolution that a classless society would no longer require a state apparatus, Bannon’s anti-statism targets the regulatory apparatus of liberal institutions, on the grounds that they should be replaced by a nativist, libertarian capitalism.

At the beginning of Trump’s second term, Elon Musk, with DOGE chainsaw in hand, briefly eclipsed the spotlight that had been Bannon’s. At that moment, the governing analogy shifted from Lenin to Mao. “The young aides Elon Musk has sent to dismantle the U.S. government reminded some Chinese of the Red Guards whom Mao Zedong enlisted to destroy the bureaucracy at the peak of the Cultural Revolution,” Li Yuan wrote in a widely circulated piece for the New York Times. Like Lenin before him, Mao championed the state’s withering as the ultimate sign of the advent of a truly communist society, and in response to the contradictions of the party-led “dictatorship of the proletariat,” he launched the Cultural Revolution to transfer power to mass politics. Musk, the world’s richest man—who is explicitly anti-communist, supports international right-wing movements, and aspires to populate Mars—subscribes to a radically different vision of life beyond the state. There is no room for the masses in Musk’s colony in outer space.

It is true that both Trump and Mao attacked higher education, as Fareed Zakaria argued in a column in the Washington Post last March about “America’s version of the Cultural Revolution.” He called out Vice President JD Vance’s provocation, “We have to honestly and aggressively attack the universities in this country… The professors are the enemy.” And he claimed that the moment was analogous to “the early days of the Cultural Revolution, when an increasingly paranoid Mao Zedong smashed China’s established universities, a madness that took generations to remedy.” For Zakaria, there can be no valid justification for destroying higher education—but on this score too, different political contexts change the meanings of seemingly analogous actions.

Put generously, Mao’s anti-intellectualism was a capacious vision of what knowledge is and who has the authority to produce it. In this view, the masses are living archives of wisdom. In the absence of formal medical infrastructure, ordinary people could become barefoot doctors and deliver medical treatment. Anyone could read and write poetry. At the same time, Mao distrusted intellectuals because independent thinking threatened his authority. Perhaps one of his greatest failures was to see enemies where there were potential comrades—another was to hold on to power during the Cultural Revolution.

Mao’s policies forced intellectuals and experts to reform their supposedly corrupted ways of thinking: Through confession, self-criticism, and manual labor, they might undergo a “change in feelings, a change from one class to another.” Some complied willingly; others were coerced; and others still died in the process, by their own hands or at others’. Revolution is a series of violent contradictions. I am a university professor at an elite institution where we wear robes to high-table dinner, and I have no illusions about my own fate in a Mao-inspired revolution. If lucky, I would end up cleaning latrines. But I also believe in intellectual life outside of academic institutions, which tend to reproduce existing social classes: A vibrant world of knowledge and sociality glimmers in encampments and undercommons. It is this world and everything it cherishes that Trump has targeted for destruction.

Ideology Soup

What is the purpose of an analogy so brittle it crumbles under the slightest historical weight? When it comes to Mao/Trump, accuracy was never the point: Many of the parallels casually slip out of the worn-out suit of Maoism into the shapeless garb of Chinese authoritarianism thrown over a mannequin of Oriental despotism. Under Trump’s second administration, wrote one commentator, “it seems as if the US is being pulled in the Chinese direction, rather than the other way around.” In that New York Times column, Li glides between resemblances with the Cultural Revolution and “Trump’s musing about serving a third term,” following the example of Xi Jinping. All that analogizing lost me: Does Trump resemble Mao? Or Xi? Or both, which would introduce another overwrought trope, about Xi being a return to Mao?

The more the Mao/Trump analogy is stretched in different directions, the more incoherent it becomes. Not long ago, Trump re-rode to office on the back of a crusade against wokeness. According to Peter Van Buren, writing in the American Conservative, signs of American-style Maoism range from “white guilt” and “intolerance toward dissent” to wearing a “soiled surgical mask to the supermarket.” On his HBO program Real Time, the comedian Bill Maher, tongue in cheek, railed against leftist attempts to “reinvent the very nature of human beings”—including biology—stating: “We do have our own Red Guard here, but they do their rampaging on Twitter.” In the UK, the conservative philosopher John Gray has warned of the perils of “Twitter Maoism” driving a digital campaign of public shaming, “the vile ritual” of public apologies, orthodoxy, re-education, and witch-hunts across universities and corporations.

To shed the last vestige of ideological coherence, recall the popular conservative meme, “Obamao,” which featured President Barack Obama’s face wearing the iconic Mao hat and jacket collar. In its hyperbole, the meme revealed a kernel of truth: Mao is an endless source of fascination, fear, projection—and an analogy as alluring as it is misleading.

The Great Reversal or a New Direction?

Fear underlies this confusion. Is the implosion of liberal democracy under Trump turning the US into China, its great political other? Is this a great reversal, a betrayal? In Li’s words: “The United States helped China modernize and expand its economy in the hope that China would become more like America—more democratic and more open. Now for some Chinese, the United States is looking more and more like China.” The vague reference to “some Chinese” provides a veneer of authentic historical experience without having to attribute it to anyone in particular. The rest of the statement can reassure the US of its intrinsic goodness by writing Trump out of its history. If Trump is a traitor—an un-American admirer of Xi and puppet of Putin—then the fantasy can be sustained that once he is gone, the US could be great again. But Trump is as American as apple pie (without the piety), which is just why he is such an uncanny and disturbing presence for liberals. The historian Julia Lovell makes a similar point: “In establishing Trump as the apostle of Chairman Mao, he can be unmasked as a fundamentally alien threat to American life.”

Such analogies rely on rhetorical strategies that couch political judgments in historical memory. Here is an excerpt from the Guardian: “Trump as viewed from China has delivered Mao-style chaos to the US.” And here is a headline from CNN: “In China, some see the ghost of Mao as Trump upends America and the world.” Lovell points out that it is mainly “Western commentators” who “have sounded the alarm about Maoism in America” by attributing the observation to Chinese people who presumably speak with the authority of historical experience. And “in doing so, perhaps unwittingly, they have written the latest chapter in a long history of making China the source of U.S. ills.” (In her book Maoism: A Global History, Lovell does, however, also help herself to problematic—even pathological—metaphors by referring to Maoism as a “dormant virus” that originated from China and replicated itself in host countries.)

The proliferation of bad analogies is a problem because they distract from the need to reinvent democracy and find an exit from capitalism. They seem to signal that any attempt to diverge from the center, even as it collapses, will lead to the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. As the historian Rebecca Karl argued in a 2022 essay called “Xi Is Not Mao,” given the state of geopolitical conflict and climate crisis, “The stakes are high, and now is the time to rise to the occasion of critical engagement rather than sink into facile historical analogies.” Historical analogy replaces structural explanation with a story about dangerous actors, and it warns readers away from any politics that might transform the conditions that produced the crisis.

Instead of relying on the false familiarity of analogy, better to approach history with an ethics of translation, looking for echoes and inspiration from past political struggles—not in order to repeat them in the present, but to reinvent them. Walter Benjamin famously described the task of the translator as keeping alive what is “incommunicable” in the original beyond its referential meaning, “for in its continuing life… the original is changed.” Maoism appealed to the Black Panthers not because the situation of Black people in the United States was analogous to that of Chinese people during the Cultural Revolution—far from it. But there was a solidarity of struggle and a translation of practice. The days of Mao are long gone in China. If their echo can still be heard across the Atlantic, that’s not because they approvingly whisper in Trump’s ear, but because they might remind all common people that power is in our hands.

Christian Sorace is an associate professor in the Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge and a fellow of Corpus Christi College.