A Good Life in Bad Times

Attack

In the 1950s, the American senator Joseph McCarthy fed the public’s suspicion that there are powerful enemies within the country, rotting out its core values. My father, mother, and uncle had good cause to fear that they would be fingered as among these enemies. They had become Communists in the depths of the Great Depression, my mother organizing garment workers, my uncle and father joining the Abraham Lincoln Brigade which fought against Fascism in Spain. After the Second World War people like them appeared as corruptors of American trade unions or as spies for the Soviet Union.

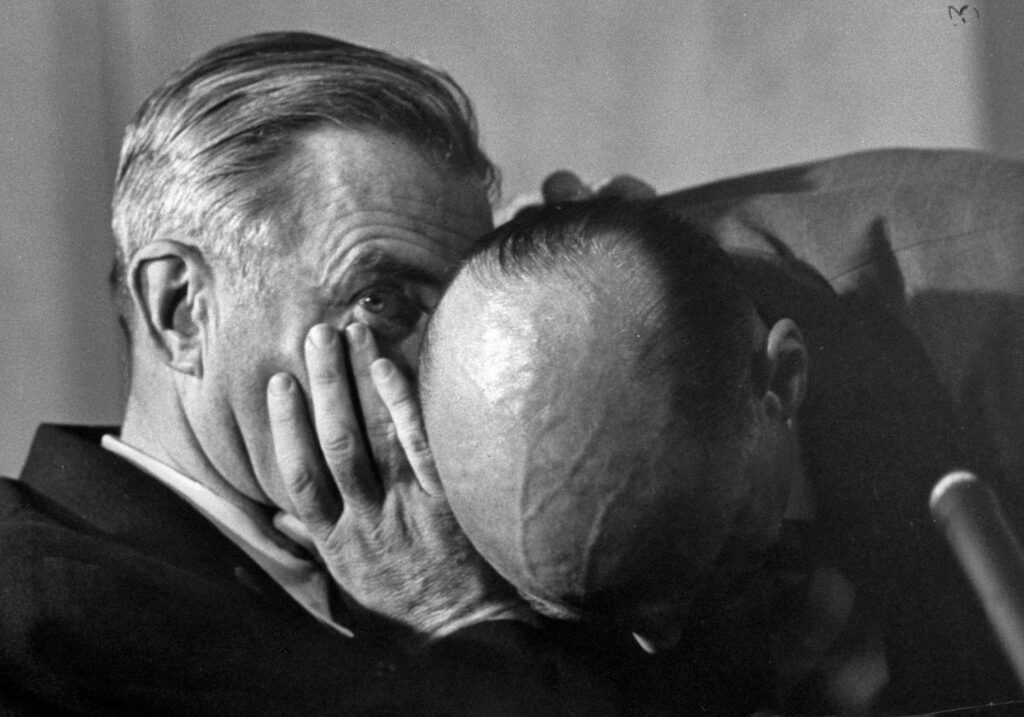

McCarthy and President Donald Trump are both charismatic performers with a base of fervent believers. And there is a more personal bridge between the two: Roy Cohn, a lawyer and political fixer. Cohn served as McCarthy’s chief counsel and later as a business adviser to the young Trump. Cohn was an expert in techniques of deception; he once had McCarthy wave in front of a gullible press a sheaf of papers supposedly listing hundreds of communist spies—the sheets, of course, proved to be blank paper. A generation later, he coached Trump in how to bluff or intimidate New York politicians when the young property mogul encountered rough weather in the city.

It was the minions of Cohn who persecuted my family. They fed our names to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), suggesting that my mother, father, and uncle be indicted for sedition, a crime which entailed long prison sentences. Thankfully, nothing came of the sedition charge, but FBI surveillance and harassment by HUAC did not go away, and reached into my own childhood. Because McCarthyism enlisted schools as well as employers in sniffing out suspected Communists, men occasionally sat in a car next to my school playground, watching me play, observing whom I played with—clues, possibly, to parents who might also be disloyal.

This harassment transformed families like ours. The less children knew about their parents’ politics, the safer those parents; silence at home meant that a kid would not accidentally betray parents to teachers. The silence worked, but families paid a price for it. However, “red diaper babies,” as the children of communists were known, could intuit, as children seem always to do, that their parents were holding something back—and inside the family, adult secrecy eroded trust. At ten years old, while I was too young to make sense of communism, I knew there was something which I should not be told about; I nagged my mother in particular, and she withdrew inside herself rather than slap me down, as a less anxiety-driven parent would have done.

I wish I had known that my parents, like many other youthful Communists, had quit the party by the time of Hitler’s pact with Stalin in 1939. It would have perhaps helped me better understand why the attacks later had so challenged them: after the War, middle-aged parents like mine would be hounded for a cause in which they no longer believed. This was a bitter irony particularly for my father, who had moved by the 1950s from the extreme left to the extreme right, a journey which quite a few other disappointed Communists made. But even so, he, like my uncle, who remained militantly on the Left, had to find a way to defend himself.

Resistance

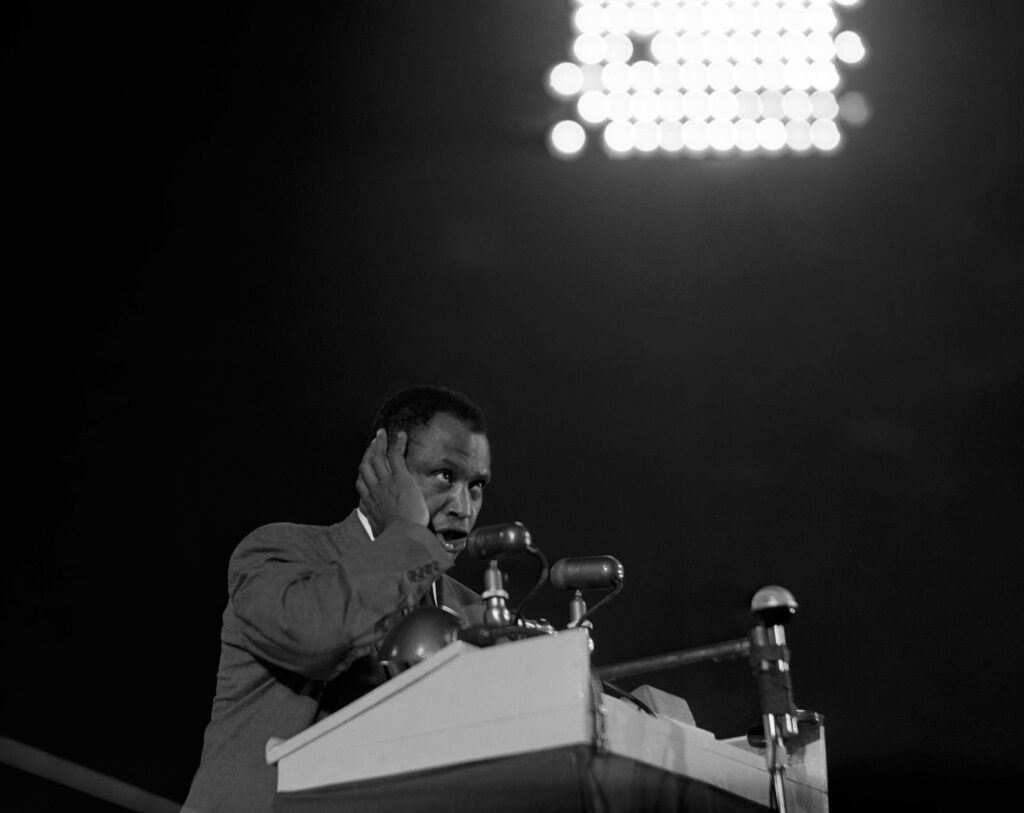

My family resisted persecution in three ways. My uncle resisted boldly, wielding the law like an axe. When you met him, “sensitive” is not a word which would come immediately to mind. In his autobiography Communist Functionary and Corporate Executive (surely he could have found a better title?), William Sennett describes with zest how he deployed the same confrontational tactics he used against McCarthyism when he later went into business; he became a feared deal-maker. He continued to be politically involved on the Left, funding a radical magazine called In These Times. To friends and family he was also a generous soul, but he didn’t let it show.

Aggressive pushback like his entails a risk that you will descend to the personally-insulting level of your aggressors. My uncle didn’t fight persecution that way, instead opposing Cohn’s insinuations with legal threats, fencing in “the defendants” (that is, Cohn’s henchmen) with one possible penalty after another, without in any way personalizing the pushback. This had a practical consequence: by treating his adversaries coolly, my uncle stood above them in court.

At the opposite extreme, survival can entail what the French call an émigration intérieure, a disengagement from the here and now. This detachment marked my father Maurice Sennett. A gentler soul than his brother, he seemed to the lawyers defending him to be emotionally absent in court. Detachment serves the same practical purposes as a thick hide: the punches of the persecutors seemed not to be landing emotionally. In our case, Cohn’s people got no satisfaction in the theatrics of the courtroom because my father appeared absorbed in some other, so-far-away realm. His withdrawal was more than a tactic. Like a monk, this child of the Chicago streets cultivated inner stillness, passing hours sitting silently and alone in an empty room.

Émigration intérieure can be traced back to early Christianity, particularly to the mindset of Christian martyrs under torture. Like the brother of Jesus, James, who was stoned to death, some martyrs did not seek out suffering but were indifferent when pain came as a consequence of their faith. Another kind of martyrdom arose with those who were purposely self-harmers, like the Valesian sect of the 100s AD who castrated themselves in order to purify their bodies. Modern and secular émigration intérieures derive from Jamesian indifference; out of faith, people withdraw from the world, come what may. The problem for my father was that he was disposed to inner stillness and contemplation, but he no longer had a faith in which to believe, such as he had as a young Communist. For a while he was tempted by Catholicism, but his heart wasn’t in it.

My mother Dorothy Sennett embodied a third response to persecution. When hauled before an anti-Communist tribunal, she was a model of courtesy, responding to hostile questions calmly rather than defiantly. What sustained her was the work she did in civil society. At the time of her hearing, she was part of a team running a housing project in Chicago. Because she was a female public servant, it was tricky to go after her. The extreme right thought that Eleanor Roosevelt, the former First Lady and an apostle for public service, was a Communist agent; garden-variety anti-communists knew, however, that they had to be careful about women in professions like teaching or social work. These working women benefitted, oddly, from stereotypes about the Maternal Mother. McCarthy avoided attacking such maternal figures—perhaps some residue of Catholic belief inhibited him, or perhaps he understood that in America it is not a good idea to attack Mom.

My mother had neither a tough hide nor was she otherworldly. The traumas of the past did not go away for her personally, even as, from 1962, she began to help devise legislation for Medicare A—America’s public health care plan for hospitalized patients. She observed a rule of silence outside the home as well as within it. At work, she avoided talking about herself, not trusting others to know about her. The higher she rose as a respected policy maker, the more she feared being outed. Colleagues at work were never invited to our house. At the end of her life, she edited and published two volumes of literature about aging, particularly about old people in need of medical care. Not bestseller material, but it created a practical bond with her readers; she had an active correspondence with them. Just as she related to colleagues at work, she wrote to readers impersonally as an expert, not as a sister. Her book collection Vital Signs remains in print.

Character

We were a privileged family, but there are elements in our history which apply more broadly, embodying three ways of resisting persecution: through aggressive counterattack, indifferent withdrawal, or social engagement rather than political jousting. Though all three forms of resistance depend on raw sensory awareness, such as the ability to sense danger, resistance itself is a more fundamental test of character. That word “character” rings a Victorian bell, as in the Victorian schoolmaster’s promise to parents to “build up the character” of their spoiled children. More deeply, character is not the same as personality. A hypochondriac can prove courageous rather than self-pitying when rising to a challenge. Similarly, economic conditions don’t predict strengths of character; the rich are certainly no better endowed with courage than the poor. In our family’s case, insensitivity, withdrawal, and secretiveness marked the personalities of the three individuals. But these psychological negatives became strengths of character when a political situation tested them.

All resisters in my parents’ generation faced a peculiar kind of threat. In his 1964 book The Paranoid Style in American Politics,the historian Richard Hofstadter suggested that political extremism of the McCarthy sort flourished largely in a realm of fantasy and paranoia. In one way this fantasy realm was quite superficial. When vigorously resisted, the persecutors tended to move on in search of other targets. Thus when my uncle, threatened by the FBI, turned the tables on the agents who menaced him, the FBI quickly lost interest. More prominent people like the playwright Arthur Miller also found they could fend off McCarthy through vociferous counterattacks, whereas the Commie-hunters stayed on the case of fellow travelers like the choreographer Jerome Robbins, who was open to discussion and compromise, and became a fixed rather than moving target. He was eventually lured into betraying the names of ex-Red friends. Cohn thought of Commie-hunting as a matter of profit and loss, to be pursued only so long as there was a publicity benefit to the persecutor.

The public passions of that time were similarly hot but not permanent. By the time McCarthy went after Communists in the US Army in 1954, his movement was fading. Fervor was at its strongest around 1950, dissolving thereafter as everyone apart from the most diehard fanatics grew tired of the endlessly-repeated message. Of course the ebbing was not much comfort to those under attack; people had to find ways to deal with the persecutions even if they were only persecuted briefly. The personal consequences lasted a long time, though, marking and scarring the personalities of those who successfully survived. The persecutions my mother suffered never left her.

How to live through bad times is the huge question addressed by philosophers like Michel de Montaigne Montaigne and Voltaire. Montaigne was preoccupied with the experiences that sustain people after they have experienced a jolt and made an émigration intérieure. Voltaire “cultivated his garden” as the result of his own persecution, living in exile yet remaining a political warrior, armed with a pen. Modern psychology frames the consequences of a jolt or attack as a matter of “post-traumatic stress syndrome,” like Paul Klee’s famous print Angelus Novus, which Walter Benjamin famously interpreted as the Angel of History. The picture shows a figure skimming the Earth strewn with rubble, the Angel being blown forward blindly while looking backward at what has been. Similarly, the word “traumatized” fixates understanding backward to the primacy of jolts or attacks or persecutions. But the persecuted, if they survive, are like the widowed, challenged to move forward with life, even if the scars of the past don’t heal, which they usually don’t.

What seems to me most important is the path pursued by my mother. She sustained herself by engaging socially, rather than battling politically or withdrawing stoically. I’ve wondered whether that way of making a life could sustain other people today, in a time which the extreme right, unlike McCarthy’s time, seems here to stay—a time of grievances and prejudices and of Hofstadter’s collective paranoia, and of monopoly capitalism and widening inequality, an endless litany of wounds which do not heal.

Nazism and Neronism

When asked what he had done during the Reign of Terror in the French Revolution, the abbé de Sieyès famously replied, “I survived.” A classic middle-of-the-road politician in modern terms, Sieyès became a target of more extreme revolutionaries as the French Revolution shifted left. He proved good at surviving by keeping his head down during the years of terror from 1792 to 1794, and then bobbed up as soon as the danger had past. A few years later he would become a top official when Napoleon took power in 1799. But his bon mot about the years of terror named a real fear. The Committee of Public Safety dictated who people could talk to, and who to avoid; how to school children in a revolutionary manner; how to dress as a loyal citizen. Any infraction could lead to harsh punishment, and some violations, like talking to the wrong people, could lead straight to the guillotine.

The danger Sieyès faced came from what sociology (Sieyès invented the word sociologie itself) has come to call a “total institution.” Places like prisons or mental hospitals for the criminally insane embody total institutions, programming and controlling every moment of an inmate’s day. In politics, total institutions have a particular backstory. They appear, as the Nazi political analyst Carl Schmitt argued in the 1930s, after a prior “state of emergency” of extreme upset and unhappiness, as during the instabilities of the Weimar years in Germany. A powerful ruler then arises, promising to set things right. Once the watershed occurs, a ruler could simply impose his will, even if, as with Trump, his own desires are inconsistent or contradictory. But total institutions, as Sieyès knew during the Terror and Schmitt saw in his own time, were more rigid structures. Particularly so in the Nazi death camps: Though people could live or die at the whim of a camp guard, rigid bureaucracy created a more effective way of exercising power, the camps timing to the hour how many and in what manner people were to be killed.

The extremes of suffering in total institutions, as the philosopher Giorgio Agamben has described Auschwitz, are composed of scenes of “bare life.” Survival is stripped down to the minimum; all that matters is getting through another day. As the inmate Primo Levi wrote, in Auschwitz people at the very bottom were described as Muslims rather than Jews, a “Muslim” referring to someone who was not any sort of human being, a starving or sick creature to whom no attention was paid by the Nazis, whereas they paid murderous, rule-based attention to the Jews.

Social relations in a total institution are not as impoverished as the image of “bare life” would suggest. For instance, Levi admitted to stealing food in the concentration camp laboratory where he was put to work, which meant that other people had less to eat; raw hunger may seem to have stripped his life down to the bare minimum of animal survival. But to his surprise Levi found that other people in Auschwitz did not blame him for surviving any way he could, and didn’t inform on him. Relations in the camp were a complicated mix of raw physical need and mutual empathy. So too today in the starvation inflicted on the Palestinians of Gaza. The news shows images of people elbowing each other aside in the struggle to get at packets and pails of food, but then reports that children and the aged are fed first. Their life is more than a bare life.

Totalized power of this sort is properly named Nazism, not fascism—which can be, as in fascist Italy, brutal but disorganized, fragmenting as power passes from a dictator’s dictates to execution on the ground. Whether in a death camp or a mental hospital, its essential character being that the rulers are absolutely in charge, from top to bottom. But there is another kind of rule from the top which is equally Schmittean in character, epitomized by the Roman emperor Nero. In the last years of his reign, he ruled capriciously for his own pleasure, abandoning those at the bottom to survive wars, plagues, and famines on their own. When reality proved too demanding, he couldn’t be bothered; he moved on to another banquet. Put broadly, the contrast between the two forms of power is that Nazism imposes rigid obedience on those below, while Neronism abandons those below to their own devices. Today, the global economy exemplifies that aspect of Neronism; a Neronian state doesn’t try to sort out the shambles of healthcare in America or the precarity of work in Europe. You are on your own. Which is to say, the state is a deus absconditus, a god who disappears.

The Nazis, like Sieyès’ revolutionaries, staged public parades and festivals to bind the masses emotionally to the ruling regime. The beheading of Louis XIV was staged as a massive piece of theatre, everyone aroused, cheering and shouting slogans the audience became more than mere spectators: Their enthusiasm made them complicit in the killing. Whereas Nero’s sort of theatre (chariot races, song contests, and even wild beast combat in which Nero himself always played the starring part) was meant simply as a diversion. The common Latin tag runs panem et circenses, bread and circuses; Nero offered them circuses but not bread.

Roy Cohn was a Neronian figure. He made persecution into a form of entertainment. He did not seek total control of those he persecuted. Whereas the Nazi regime would relentlessly hunt down Communists, Cohn only sought to make a show of doing so; his aim was to create a theatrical scene of unmasking and accusing. After he moved on, people were left to pick up the pieces as best they could.

In my parents’ generation, this was a problem both for persecuted individuals and for the communities in which they lived. What remained after McCarthy was wariness of the Other, both of strangers and strangeness; anti-immigrant sentiment flared up in the early 1950s, as did a flare-up in homophobic persecutions. Distrust of the Other does not heal easily if at all. Mutual distrust will be one legacy of the post-McCarthy era to post-Trump America.

An all-consuming adversarial relationship to power is not enough to make a full life. Obsession of any sort is claustrophobic. I think my mother felt the claustrophobia of Communist Party politics, and it turned her to a more social engagement with other people, through the institutions of civil society. Today, however, that turn would be more difficult. Schools, hospitals, housing, libraries, playgrounds, and the other institutions of civil society have been left without resources. Like the rusting bridges of New York City, they show undeniable and dangerous signs of collapse. Yet our Neronian rulers have had no abiding interest in making them work. To refigure Agamben’s phrase “bare life,” when demands are made on the state, the usual response is something like “the cupboard is bare.” To me, the task in front of us is how to renew our institutions, how to think fresh from the ground up. As a slogan, you could say that it’s a matter of putting the social back into socialism.

During the time recounted in this essay, Richard Sennett grew up in the Cabrini Green housing project in Chicago. He then became a writer and teacher, working most recently at the London School of Economics. This essay is an adaptation from the author’s forthcoming book.