A Modern Counterrevolution

In a blizzard of executive orders and emergency declarations, President Donald Trump has taken a hatchet to the American government and the global order. He is wrecking the administrative state, shuttering entire agencies and departments, laying off federal workers, firing inspectors general. He is deporting permanent residents for speech protected by the First Amendment, revoking visas from international students, sending immigrants to the military camp at Guantánamo Bay and a mega-prison in El Salvador, and trying to eliminate birthright citizenship. He is defunding research universities and attacking the legal profession. He is threatening draconian tariffs on the country’s closest allies and neighbors, demeaning their leaders, and pulling the United States out of longstanding international commitments. Every day, he launches another unprecedented offensive or changes course; he creates ambiguity and fuels confusion, leaving his critics to second-guess themselves while giving himself cover.

He remains extremely popular with his base, even if his overall ratings have dropped to record lows. His critics, though, attack him six ways from Sunday. They call him a fascist, an authoritarian, a tyrant, the kleptocratic tool of tech billionaires, a profiteer, a reality-TV impostor, the embodiment of toxic masculinity, a bully. Yet none of these labels fully captures the scope or the coherence of what is happening in the U.S. today. These diagnoses focus too much on the individual, and this is an individual who, like a virtuoso illusionist, keeps his audience mesmerized by the spectacle but distracted from what is really going on. The radical developments underway must be placed in deeper perspective. Not just because so many of them were prefigured in the 900-page Project 2025 blueprint but also because much larger forces have powered the rise of far-right leaders across the globe.

In fact, the Trump II administration represents the demolition phase of a new offensive in a decades-long counterrevolution. The conservative activist Christopher Rufo said in a recent interview with the New York Times: “What we’re doing is really a counter revolution. It’s a revolution against revolution.” Mr. Rufo added: “I think that actually we are a counter radical force in American life that, paradoxically, has to use what many see as radical techniques.” In effect, President Trump’s actions during the first hundred days of his second mandate are the latest episode in a vast and coherent modern counterrevolution with a longer historical arc and a broader global reach.

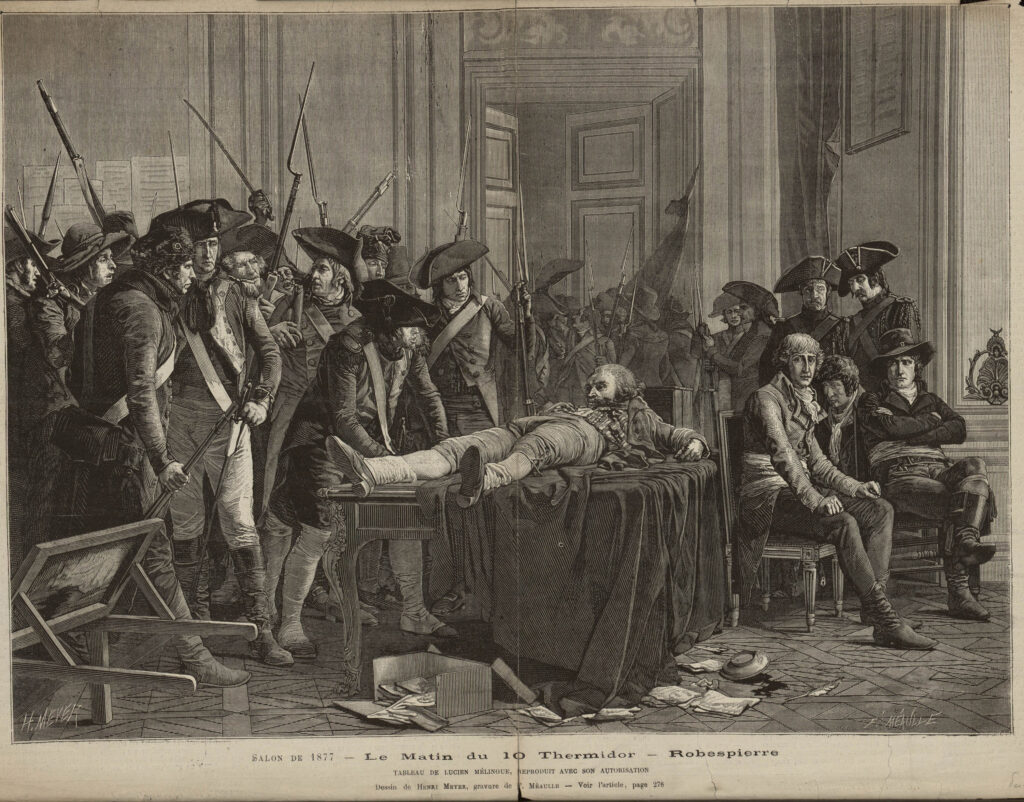

Consider Marx’s argument in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. The rise of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte in 1848, Marx claimed, was not simply a “great man” story; instead, it demonstrated “how the class struggle in France created circumstances and relationships that made it possible for a grotesque mediocrity to play a hero’s part.”1 The sentence’s humor should not obscure its theoretical thrust. Likewise, our diagnosis of President Trump today must focus on the broader social conflicts and economic forces that are propelling history at a global level, not on the rise of any one individual—even if he resembles a grotesque mediocrity.

I don’t want to minimize the extravagance or the radical nature of President Trump’s daily spectacles—what Marx referred to, speaking of Louis-Napoléon, as his “coups d’état en miniature every day.” But instead of focusing on the daily sleights of hand, it is important to understand, first, the broader strategies that motivate them and, then, their larger historical context.

The Methods

In the first 100 days of his second mandate, President Trump has deployed three main strategies:

(1) Creating internal enemies. In a record 139 executive orders—more than any previous U.S. president, including FDR—President Trump has set his crosshairs on a handful of targets and turned them into internal enemies: D.E.I. candidates (a proxy for African-American, Hispanic, disabled, and transgender persons), “gender ideology” (a proxy for LGBTQ+ persons), global climate-change advocates (or anyone who supposedly contributes to “climate anxiety”), immigrants and international students, top research universities, federal workers, and anyone who investigated or prosecuted him previously.

President Trump is actively demonizing those new internal enemies. In the first press conference following the air collision at Reagan International Airport on January 29, he immediately, without any information, blamed D.E.I. for the accident, disparaging African-American, transgender, and disabled air traffic controllers as less qualified than their white, cisgendered, and able-bodied counterparts. He and his allies accused Kamala Harris of being a “D.E.I. candidate,” a “D.E.I. hire,” “our D.E.I. vice president,” and of being “dumb.” President Trump has targeted transgender persons in his executive orders, claiming, for example, that transgender women are simply gaining “access to intimate single-sex spaces and activities designed for women, from women’s domestic abuse shelters to women’s workplace showers.”

One key device he uses to demonize internal enemies is to designate them as bad actors and strip them of legal protections. President Trump has added the Tren de Aragua narcotics trafficking organization to the U.S.’s list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) for “conducting irregular warfare and undertaking hostile actions against the U.S.”—and he invokes that to characterize any Venezuelan immigrant in the U.S. as a potential terrorist. He has also invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to claim that Venezuelan immigrants are alien enemies—never mind that the U.S. and Venezuela are not at war. President Trump contends that the International Criminal Court in The Hague is “an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States.” As a result, American staffers are now potentially subject to U.S. sanctions; anyone who provides the lead prosecutor with any services faces losing their assets in the U.S., up to $1,000,000 in fines, and 20 years in prison.2 And then, the administration cites the fact that Hamas and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine are considered FTOs to characterize people protesting Israel’s war in Gaza as supporters of terrorism, even though their speech is protected by the First Amendment (pace Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project).

Another way of targeting perceived internal enemies is to declare minor emergencies—such as under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act or the National Emergencies Act or, again, the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. President Trump has already announced a dozen such emergencies. There is one at the southern border of the U.S., which he contends is being “overrun by cartels, criminal gangs, known terrorists, human traffickers, smugglers, unvetted military-age males from foreign adversaries, and illicit narcotics that harm Americans, including America.” Now the U.S. military polices it. President Trump has declared an emergency over the “extraordinary threat posed by illegal aliens and drugs, including deadly fentanyl” as a basis for imposing tariffs on Canada, China, and Mexico. He has also declared an emergency regarding “the United States’ insufficient energy production, transportation, refining, and generation.”

The Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt defined a sovereign as “he who decides on the exception.”3 A few decades later the philosopher Giorgio Agamben argued that Western societies had entered “a permanent state of exception.”4 But President Trump deploys emergencies merely as a technical device to grab executive power and demonize internal enemies; they are just one tool among others and do not amount to a global state of exception. Instead, they allow him to claim as his own the grey areas of the law and expand their borders (as with the deportation of the Columbia students and permanent residents Mahmoud Khalil and Mohsen Mahdawi, or the blanket defunding of universities under Title VI).5 Michel Foucault referred to such methods as “illégalismes”: They create a space between the legal and the illegal where it is political contest that determines what is permitted and what is not.6

(2) Eliminating those internal enemies. Then President Trump eradicates or neutralizes these perceived foes. He is cutting D.E.I. programs, not only throughout the federal government but in private industry as well. By means of executive orders, he is coercing law firms like Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom to eliminate their affinity groups and outreach programs. The administration is trying to put an end to gender-affirming care, banning reimbursement by Medicaid for youths under 19. It revoked more than 1,500 student visas at over 100 colleges and universities—and although it is reinstating some, it is threatening even more. It is eliminating the jobs of tens of thousands of federal workers. It is deporting international students and permanent residents who have protested the way Israel is conducting its war in Gaza. President Trump has vowed to send 30,000 immigrants to Guantánamo. The administration has imposed a quota of 75 arrests per day per ICE field office—or 1,200 to 1,500 daily detentions. Immigration sweeps are taking place across the country; in some, hundreds of people are arrested at a time. Within days of the inauguration, the former Columbia Justice-in-Education scholar Nascimento Blair was arrested and deported to Jamaica. Some people who are being targeted choose to leave the U.S. or refuse to reenter it even lawfully or go into hiding, all of which only serves the government’s agenda.

(3) Winning the hearts and minds of the American people. Every day comes a new shocking segment of what seems like reality TV. According to a New York Times article, Mr. Trump told his aides before taking office in 2017 that they should “think of each presidential day as an episode in a television show in which he vanquishes rivals.” They have outdone themselves, thanks partly to the technological revolution. Musk once described Twitter (before he bought it) as an access point to the giant id of the American people. Truth Social and X are now giving him, President Trump, and others constant and direct access to the national libido. Like Louis-Napoléon per Marx, President Trump has been “executing a coup d’état en miniature every day,” and to his MAGA base, this has been a constant source of entertainment and vindication. Toward the end of his and Vice President J.D. Vance’s verbal assault on President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine at the White House in late February, he acknowledged: “This is going to be great television.”

These three strategies permeate the first 100 days. In order to make sense of them, I propose taking a step back—conceptually, historically, and contextually.

A Framework

To explain what I mean when I say that the second Trump presidency is best understood as the demolition phase of a new offensive in a decades-long counterrevolution, let me take each term in turn.

First, a “counterrevolution” has been underway since the invention of counterinsurgency warfare in the 1950s and ’60s by French, British, and American commanders during the wars of independence in Algeria, Indochina, Malaya, Vietnam, and other former colonies. Those campaigns gave birth to counterinsurgency warfare logics and strategies—also known as unconventional or antiguerrilla warfare, or, as the French would say, “la guerre moderne,” modern warfare. And then those logics and strategies were brought back and applied on domestic soil.

The logic of counterinsurgency warfare rested on a unique vision, essentially shaped by Mao’s belief that society is composed of three groups: a small group of active insurgents, the large mass of passive citizens who can be swayed one way or the other, and a small minority of counterinsurgents. Counterinsurgency warfare strategies were developed to, first, gather total information on the population in order to identify the internal enemies; second, weed them out; and third, gain the allegiance of the passive masses. David Galula, a French commander in Algeria in the late 1950s and a founding figure of modern warfare, expressed it in simple terms: “In any situation, whatever the cause, there will be an active minority for the cause, a neutral majority, and an active minority against the cause. The technique of power consists in relying on the favorable minority in order to rally the neutral majority and to neutralize or eliminate the hostile minority.”7

These counterinsurgency strategies were first deployed in European and American colonies during the wars of independence. After 9/11, the U.S. redeployed them in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Under President George W. Bush, there were mock executions, waterboarding, and indefinite detention at Guantánamo; under President Barack Obama, there were drone assassinations, total surveillance, and the summary execution of a U.S. citizen abroad. The methods were refined by American generals (David Petraeus, James Norman Mattis, H.R. McMaster) into a population-centric counterinsurgency approach that was then inculcated to American soldiers via the revised U.S. Army/Marine Corps counterinsurgency field manual FM 3-24, issued in 2006. General Petraeus’s field manual repeats Mr. Galula’s theory practically verbatim.

The counterinsurgency warfare strategies then returned home to roost. An early example was J. Edgar Hoover’s development of the COINTELPRO program on U.S. soil to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” perceived internal threats. It targeted a wide range of so-called internal enemies, from feminists, communists, and Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., to the Nation of Islam and the Black Panther Party. It used counterinsurgency strategies against what it perceived as revolutions-in-the-making, like the Black Power movement or the anti–Vietnam War protests.

Similarly, in the aftermath of 9/11, the three core strategies of counterinsurgency returned to the U.S. itself and then were increasingly domesticated. First, total informational surveillance of the population (the NSA programs revealed by Edward Snowden) in order to distinguish between the internal enemies (Muslim-Americans, undocumented immigrants, Black radical protesters) and the passive population. Second, paramilitarized policing to eradicate those internal extremists (the 1033 Program, which transferred at no cost surplus military warfare equipment to local police forces; the use of drones). And third, a campaign to win the hearts and minds of the passive majority (the social-media presidency, the reality-TV presidency).

Bringing counterinsurgency techniques home and applying them to one’s own citizens, based on the belief that some are internal enemies engaged in a supposed revolution, can be called “a counterrevolution.” Herbert Marcuse already used the term in his 1972 book Counterrevolution and Revolt to characterize the repression of anti–Vietnam War protests at Kent State University and Jackson State College. “The Western world has reached a new stage of development,” Marcuse declared in the very first sentence of the book: “now, the defense of the capitalist system requires the organization of counterrevolution at home and abroad.”8 Insofar as this counterrevolution was, and is, the brainchild of la guerre moderne—by contrast to older counterrevolutions that sought to reinstate monarchs—I would call it “the modern counterrevolution.”

Second, the Trump II administration represents a “new offensive” of the modern counterrevolution because it is not unique but is one more episode in the counterrevolution conducted on American soil. There have been prior offensives since 9/11, including the Global War on Terror initiated by President George W. Bush; and before 9/11, there had been President Ronald Reagan’s conservative revolution and War on Drugs in the 1980s; and even before that, President Richard Nixon’s crackdown on Blacks and anti–Vietnam War protesters, Mr. Hoover’s COINTELPRO program, and the Red Scare during the McCarthy Era. These offensives tended to be conservative, but their logic became so ubiquitous post-9/11 that Democrats partook in them, too.

I described the last offensive in a book titled The Counterrevolution: How Our Government Went to War Against Its Own Citizens, which was published in February 2018, during President Trump’s first term. At the time, I argued that he was infusing the counterinsurgency warfare paradigm with a white nationalist populism that targeted Muslim-Americans (the Muslim Ban, the surveillance of mosques), immigrants from Latin America (child and family-separation policies, the discourse about Mexican “rapists,” the construction of the wall at the U.S.-Mexico border), and Black Lives Matter protesters (militarized policing in Ferguson and elsewhere). This all came to a head during the demonstrations over George Floyd’s killing in the summer of 2020, when President Trump deployed the 82nd Airborne Division to Washington, D.C., and mobilized the military police and a U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopter as though the site were, as Defense Secretary Mark Esper put it then, a battlefield that needed to be “dominated.” The military police tear-gassed and shot peaceful protesters with rubber bullets, clearing the path for President Trump to march with Mr. Esper and his highest-ranking general, Mark A. Milley (in full combat uniform), for an infamous photo-op of the president, Bible in hand.

Third, I say that this is the “demolition phase” of the latest offensive because President Trump is taking a wrecking ball to the federal government as we know it, while simultaneously hardening the counterinsurgency strategies. Like the real-estate developer that he is embarking on a gut rehab, President Trump is bulldozing the federal edifice. He is slashing the federal workforce (down by approximately 12% as of last month), shuttering federal agencies (the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Department of Education, the U.S. Agency for Global Media, the Minority Business Development Agency), firing inspectors general across 17 agencies, and taking control of independent agencies. Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) are cutting the federal budget by $150 billion (by fiscal year ending September 2026) and firing thousands more federal workers. President Trump is demolishing the American administrative state as we know it, at warp speed.

The Objectives

The president is single-handedly—literally, by signing a record number of executive orders—seizing complete control of the executive branch to create an imperial presidency with no checks or balances.9 Even though the Republican Party controls both chambers of Congress and has pledged fealty to him, President Trump is avoiding using legislative power as much as possible, effectively ignoring Congress. Having secured a conservative supermajority on the U.S. Supreme Court, he is mostly complying with the lower federal courts—confident that judicial review will ultimately vindicate him (as it already has: directly, in the case of presidential immunity, or indirectly, in cases supporting his political agenda on abortion, climate change, etc.).10 His administration is also flooding the court with “emergency applications” that will go on the justices’ shadow docket, allowing for little if any reasoning to rubber-stamp the administration’s actions.

This radical blueprint does not seek to eliminate the federal government or devolve decision-making to the states. It is not about states’ rights: President Trump will exercise federal power the minute he disagrees with a state policy. Instead, he is turning the federal government into a leaner and more forceful instrument of police powers—enforcing borders, brutally deporting people, banning D.E.I. and so-called gender ideology, policing bathrooms, imposing tariffs and economic sanctions, overseeing universities and law firms. In the immigration context alone, the Trump administration has called for what amounts to, according to the New York Times, “more than a sixfold increase in spending to detain immigrants.” Its vision of the federal government is highly active and interventionist. It is nationalist and protectionist, as well as isolationist in some respects (with the U.S. withdrawal from the World Health Organization, the Paris Climate Agreement, and the UN Human Rights Council).

President Trump is also using federal powers to ramp up the privatization of the U.S. economy. Ronald Reagan had inaugurated a wave of privatization and reregulation (often mistakenly called “deregulation”). Some denounced this as “neoliberalism” back then—but today, if anything, neoliberalism is on steroids, with a throwback to earlier forms of corporatism. Government agencies like NASA are outsourcing their work to private entities like SpaceX, which are reaping billions of dollars for tech billionaires. During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, under Trump I, the U.S. government decided to fund private pharmaceuticals to produce a vaccine in record time. Under Operation Warp Speed, the federal government extended billions to Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, Moderna, Novavax, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer. These so-called public-private partnerships, funded by U.S. tax dollars, are the model for future federal R&D grants to be used across various industries: in the military, through contracts with Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and SpaceX; in immigration, through private prison companies like the GEO Group and CoreCivic. This is a familiar model from the Third Reich, which operated through large private consortiums such as I.G. Farben, Krupp, or Bosch. Meanwhile, federal funding to nonprofits and university research will evaporate. But make no mistake: This is a vision of big government.

President Trump has not staged a coup d’état. Not yet, at least. He won the popular vote, every swing state, and the Electoral College handsomely in the 2024 election. Everything he has done from the Oval Office and Mar-a-Lago, he had warned that he would. So far, his administration has been defending the legality of its actions in federal court, forcefully. And, with just a few ongoing exceptions (Judge James Boasberg’s ruling on the Venezuelan deportations; Judge Paula Xinis’s ruling about Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia, a citizen of El Salvador who was illegally deported from the U.S.), it has been complying with federal court orders. Then again, Louis-Napoléon, who was also elected president—of the Second French Republic in late 1848, by nearly 74% of the male franchise—did not stage his coup until the end of his presidential mandate, in late 1851, in the face of a term limit.

I set aside characterizations like “fascist,” “authoritarian,” or “totalitarian” to describe President Trump and this moment. “Fascism” is too closely associated with the fasces of Mussolini, Hitler’s Third Reich, and mid-20th century Europe. Historical precedents can be useful points of contrast and comparison, but lump too many of them together and their essential features get lost; plus, the U.S. has a distinct history with chattel slavery, settler colonialism, and racism. “Authoritarianism” is too bland a term, underdefined and all-encompassing. “Totalitarianism,” as least as Hannah Arendt used it, elides the important differences between fascism and Stalinism. The present is unique and deserves its own diagnosis.

A Modern Counterrevolution

I am using the term “counterrevolution” in several formal senses. First, as I have said, because President Trump is deploying counterinsurgency warfare strategies on domestic soil—with the disappearance of permanent residents, abusive renditions to Guantánamo or in cages in super-max prisons abroad, and so on. There is the resulting uncertainty and terror as well: The Trump administration has confirmed that Mr. Abrego Garcia was improperly deported to El Salvador but also that it has no intention of ensuring his return to his family in Maryland. Such methods characterize the most brutal forms of wartime counterinsurgency—alongside waterboarding, disappearances, rendition—of la guerre moderne.

Second, the Trump administration is trying to consolidate executive power in the hands of the modern equivalent of an absolute monarch, reversing the values of the Founding in 1776 or the Refounding in 1866. In this sense it is comparable to how historians of the French Revolution of 1789 understood the counterrevolution that followed, for instance in Vendée: as an effort to reverse universalist values—liberté, égalité, fraternité—and return France to monarchical rule. To be sure, everyone in the U.S. claims the mantle of the Founding Fathers. The rebels of the Southern Confederacy believed that they were the true heirs of George Washington and the slave-holding signatories to the Declaration of Independence. But President Trump’s nationalist populism does in fact go against the universalist aspirations of the American Revolution and the early Republic. Those aspirations were not realized at the time because of chattel slavery, the genocide of indigenous peoples, and the coverture of women; but they are defining values nonetheless, and today they are being negated, for instance by the effort to deny birth-right citizenship or equal rights for transgender persons.

Third, the Trump II administration is a counterrevolution in the way that radical political thinkers of the 19th century, such as Marx or Engels, used the term to describe the repression of the working class. The counterrevolution today attacks the U.S. administrative state that was built to protect the middle and lower classes and the disadvantaged during the New Deal, and was then further developed to avoid precarity in modern life. It goes after social services and support systems like Medicaid at home and USAID abroad.

And fourth, this is a counterrevolution in the vein of the military coups in Indonesia in 1965–66, Chile in 1973, or the Democratic Republic of the Congo and other countries in Africa and Southeast Asia when they were decolonizing. In his 1971 book Dynamics of Counterrevolution in Europe, 1870–1956, Arno Mayer set out a typology with seven forms of counterrevolutions: pre-emptive, posterior, accessory, disguised, anticipatory, externally licensed, and externally imposed.11 Walden Bello, in Counterrevolution: The Global Rise of the Far Right, proposes a “dialectic of revolution and counterrevolution,” suggesting that the two always need to be understood through their productive tensions.12 None of these analyses perfectly describes the present moment partly because all applied to more openly militaristic regimes. Still, President Trump’s approach to the modern counterrevolution has elements of the preventive and the anticipatory. My own view is that it is not so much the fear of a revolution that is driving it as the desire to consolidate executive power and make a profit by creating the illusion of a revolution. We might call it an illusionist counterrevolution.

This raises the question of what supposed revolution, if any, this modern counterrevolution is responding to. To Mr. Rufo or Steve Bannon, a former Trump adviser, in the United States and to Prime Minister Victor Orbán of Hungary or Marine Le Pen, the leader of the far-right in France, open borders and “uncontrolled immigration,” the changing nature of the nuclear family, Critical Race Theory, and Gender Studies all represent a revolutionary takeover by “wokeness.” Mr. Rufo decries a cultural revolution with its “ideological component coming from the D.E.I. departments, coming from HR, that speaks of so-called whiteness as a pathology, as a kind of mark, a kind of stigmata.” To many others, though, all that looks like evolution, not revolution.

Back in 1972, Marcuse famously said of the police repression of the anti–Vietnam War protests: “The counterrevolution is largely preventive and, in the Western world, altogether preventive. Here, there is no recent revolution to be undone, and there is none in the offing.”13 Likewise, I see no real revolution either in recent history or in the making. Especially not when so many seminal changes since the 1960s have been so easily undone: Roe v. Wade, overturned; D.E.I. programs, dismantled; transgender protections, eliminated. But whether it is a revolution or mere evolution, in any case, President Trump’s onslaught against it certainly is part of the “modern counterrevolution.”

The Driving Forces

And a vast offensive this is, powered by broader geopolitical, macroeconomic, social, technological, demographic, and cultural forces that explain the rise of President Trump and like-minded leaders worldwide.

At a gathering in Madrid in February, before a huge audience of extreme-right followers, leaders of far-right parties from throughout Europe took turns denouncing “wokeness” and gender studies, environmentalism and immigration—among them: Ms. Le Pen (from the National Rally in France), Santiago Abascal (from Vox in Spain), Matteo Salvini (from the League party in Italy), Geert Wilders (from the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands), André Claro Amaral Ventura (from Chega in Portugal). According to one account of the gathering in the New York Times, speakers “skewered the ‘liberal fascists’ who they said had replaced Christian civilization with ‘a sick Satanic utopia,’ the ‘creeps’ who ‘want to turn our children into trans-freaks,’ and the supposed ethnic replacement of native-born Europeans by immigrants.” And for Prime Minister Orbán this was glorious: “Yesterday we were the heretics,” he declared. “Now we are the mainstream.”

Across the globe, geopolitical and macro-economic shifts—globalization, financialization, the effects of climate change, and the rise of new digital technology, social media, and artificial intelligence—have fueled vitriolic attacks on immigrants. In the U.S. and Western Europe, anti-immigrant discourse is at the heart of a nationalist populist platform that calls for the protection of national borders and the improvement of the lives of the people within the nation— “America First,” “La France d’abord pour les Français,” “Zeit für Deutschland,” Brexit, and so on.

The Lakner-Milanovic graph—aka the “elephant graph”— represents the global change in income growth by income percentile between 1988 and 2008. Many economists, including Paul Krugman, interpret it as evidence of the detrimental effects of globalization on the lower and middle classes in Western countries. Nonpartisan research, for instance from the PEW Research Center, confirms that “the wealth gap between America’s richest and poorer families more than doubled from 1989 to 2016.” Along most metrics, middle-class Americans are worse off today than they were before the Great Recession of 2008; only the wealthiest tranches of American society have gained since then, significantly.14

And 12 of the last 16 years were under Democratic administrations—meaning that inequality in the U.S. has grown mostly under the supervision of a Democratic Party that has touted neoliberalism since Bill Clinton’s presidency and has held at bay more progressive politicians like Bernie Sanders. Globalization has also eroded the two-party systems of many countries, which has made many governments timid about redistributive policies, and that in turn has been fueling nationalist populism.

As technological advances and artificial intelligence transform advanced Western countries from service-oriented economies into gig economies, more and more American workers are becoming contractors and vendors who need to obtain their own health insurance and have no job security. A new social tranche is joining the precariat.

Projections by the U.S. Census Bureau indicate that by 2050 non-white persons will outnumber non-Hispanic white persons in the U.S. Falling birth rates are a major concern for Musk, a vocal white-forward/whites-first pronatalist. These developments, or at least some perceptions of them, are fueling the MAGA movement, whose adherents are at least 60% white, Christian, and male, and mostly retired, over 65. A sense among MAGA supporters that their lives are stagnating and that they are suffering from inflation and higher costs at the gas pump and the grocery store is fueling a set of hateful ideas. The “great replacement” theory: White people are going to be replaced by immigrants and overseas workers. The “criminal invasion” thesis: Immigrants are criminals, are flooding the country, and need to be put away. And “trans-exclusionary radical” movements: Transgender persons, especially transgender women, present an existential threat to the family, social reproduction, and civilization itself.

Cultural shifts are important as well, as Stuart Hall demonstrated with his analyses of the Thatcherites at the turn of the 1980s.15 Fox News is shaping the way Americans think about their political reality, as are social media, especially Truth Social and X, which is now in the hands of the extreme-right. This is true abroad as well, with media moguls like Vincent Bolloré in France, Rupert Murdoch, and others. As political propaganda goes global, information has become exponentially easier to disseminate, almost uncontainably.

One result is greater political polarization. Nationalist populism is at the core of the modern American counterrevolution today, just as it is in France or Germany. It is the main dogma of most people in the MAGA movement, including its ideological leaders, such as Stephen Miller, the White House deputy chief of staff for policy, and Mr. Bannon, with his Breitbart News. Bannon recalled in an interview earlier this year the moment he identified Mr. Trump as the perfect spokesperson for his populist, nationalist views. It was at a political rally in Hanover, New Hampshire, in May 2014: “This guy—this guy is the personification of what we need. He’s a hammer, he’s a man’s man.”

Mr. Bannon was channeling Tea Party populism at the time, and he would throw his entire weight behind Donald Trump. The future president reciprocated with his own unique brand of nationalist populism and patriotism, quickly cannibalizing votes from the white working class, union members, and other traditional Democratic supporters. But while Mr. Bannon frequently has said that he wants to “soak the rich,” favors higher taxes for the wealthy and corporations, and thinks tech billionaires are “techno-feudalists,” President Trump has formed an alliance with the wealthiest moguls. They include the tech billionaires present at his second inauguration but also another cadre of donors and benefactors, such as Timothy Mellon, Miriam Adelson, and Linda McMahon, as well as older established GOP elites who resisted him at first but have since fallen in line. These extremely wealthy people—referring to Russia, we would call them “oligarchs”— understand only too well that it is in their financial interest to dismantle the federal regulatory state.

And yet President Trump also manages to draw the support of rural populations who view themselves as the antithesis to urban elites and urban dwellers, as the protectors of family values. He also inspires evangelicals, moral-majority voters, and white nationalists (see the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017). And now, too, growing segments of Black and Latino men, who have been pulled away from the Democratic Party. The result is an unexpected coalition of seemingly odd bedfellows. So much, then, for the centrist Democratic-Republican consensus of yore—a form of peaceful cohabitation and alternation that long benefited the old elites, the Ivy Leaguers, and the political dynasties (the Kennedys, the Bushes, the Clintons). Today, both the billionaires and the MAGA base want to dismantle the federal regulatory state as we know it and replace it with a lean police state focused on military and police spending, and the enforcement of the traditional family, conservative beliefs, borders, and tariffs.

Engels once remarked that a revolution requires audacity: “in the words of Danton, the greatest master of revolutionary policy yet known, de l’audace, de l’audace, encore de l’audace!”16 This applies to modern counterrevolutions as well. Mr. Obama’s “audacity of hope” pales in comparison to what President Trump has done in the last 100 days.

The Revolt

Will President Trump manage to so deeply restructure the U.S. government during the next four years that this political moment constitutes a long-term inflection point, like the New Deal? If so, we need to brace ourselves for a fundamentally different country—and a different planet. This new mode of governing goes hand-in-hand with climate-change denial, and it is hard to imagine the rest of the world dealing successfully with global warming without the U.S.’s active participation. In his book Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto, Kohei Saito warns of “climate fascism” (extreme inequality and strong state power) or “climate barbarism” (extreme inequality and weak state power).

But there may be a backlash and a pendulum swing toward the administrative state or even further, toward some form of egalitarian collectivism or cooperation. Considering the inevitability of climate change, Mr. Saito also describes the possibility of “climate Maoism” (equality and strong state power), and he makes the case for a fourth option, “degrowth communism” (equality with cooperative and mutualist arrangements). But both of these alternative futures would require a concerted social movement.

In the U.S. so far, the Democrats have mostly taken a Muhammad Ali “rope-a-dope” strategy, to borrow from the strategist James Carville. Or perhaps even what Mr. Carville calls “roll over and play dead”: “Allow the Republicans to crumble beneath their own weight and make the American people miss us.” For a moment, it seemed as though the stock market collapse caused by President Trump’s so-called reciprocal tariffs might cause a U-turn in popular opinion, but his prompt postponement preempted a reckoning. More shock-and-awe episodes of this kind, such as the browbeating of President Zelensky in the Oval Office, are likely—to be followed by global disbelief and repugnance, and then course reversal and a momentary return to quiet before the storm.

The only counterpower in the U.S. at this point seem to be the lower federal courts, which have preliminarily enjoined over a dozen executive orders. The sole form of concerted resistance are the many lawsuits brought by Democratic attorneys general, legal nonprofits like the ACLU and the Center for Constitutional Rights, civil rights lawyers, and some law firms; and they have been effective at impeding or delaying the demolition phase that is Trump II, at least at the federal district court level. So far. It is uncertain how long the executive branch will abide by or enforce federal district court orders enjoining it. The constitutional crisis that many legal scholars fear may still be in the offing. The Trump administration is, for example, defying the federal courts on two deportation cases. And Vice President Vance has advised President Trump: “when the courts stop you, stand before the country like Andrew Jackson did and say: ‘The chief justice has made his ruling. Now let him enforce it.’”

For now, though, the mounting litigation is fueling growing resistance. Widespread cheering erupted on campuses across the country when Harvard University refused to comply with the Trump administration’s letter demanding audits of academic departments and instead filed suit. Massive demonstrations are held on Saturdays throughout the country, and a National Day of Action against Donald Trump is planned for today, May 1.

The pages of The Ideas Letter are not the right place for me to delve into praxis, so I will end here. But I hope that the critical framework of “the modern counterrevolution” can help identify new avenues for how to resist. There are many ways to revolt, as Marcuse reminds us in the very title of his book Counterrevolution and Revolt, and history shows that when people retain their values, counterrevolutions rarely succeed.

Bernard E. Harcourt is a professor at Columbia University and the École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris. A critical theorist and active human rights attorney, he is the author of Critique & Praxis: A Critical Philosophy of Illusions, Values, and Action (2020).

Special thanks to Seyla Benhabib, Elizabeth Emens, Jeremy Kessler, David Pozen, Charles Sabel, Fonda Shen, and my colleagues on the Columbia faculty for comments on an earlier draft. I am grateful as well to Leonard Benardo and Stéphanie Giry at The Ideas Letter.

- Karl Marx, “Preface to Second Edition,” in Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (International Publishers, 1964/2024), at p. 6. Friedrich Engels made the same point in his articles on Germany: to show that revolutions, as well as counterrevolutions, “were not the work of single individuals, but spontaneous, irresistible manifestations of national wants and necessities, more or less clearly understood, but very distinctly felt by numerous classes in every country.” Frederick Engels, Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany, in the Marx and Engels Collected Works, Vol. 11, p. 6. ↩︎

- Open Society Justice Initiative et al. v. Donald Trump, Opinion and Order, Doc. 56 Case 1:20-cv-08121-KPF, April 1, 2021 (Katherine Polk Failla, Judge, Southern District of New York). ↩︎

- Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, trans. George Schwab (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1985), at p. 5 (in the original, in German, “Souverän ist, wer über den Ausnahmezustand entscheidet” in Carl Schmitt, Politische Theologie: Vier Kapitel Zur Lehre Von der Souveränität (Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1922), at p. 9). ↩︎

- Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception, trans. Kevin Attell (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2005), at p. 87. ↩︎

- In The Counterrevolution: How Our Government Went to War Against Its Own Citizens (New York: Basic Books, 2018), Chapter 12, I argue that it is a state of legality and not a state of exception. ↩︎

- Michel Foucault, The Punitive Society: Lectures at the Collège de France 1972–73, ed. Bernard E. Harcourt, trans. Graham Burchell (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015). ↩︎

- David Galula, quoted in Harcourt, The Counterrevolution, at p. 30. ↩︎

- Herbert Marcuse, Counter-Revolution and Revolt (Boston: Beacon Press, 1972), at p. 1. ↩︎

- Ash Ahmed, Lev Menand, and Noah Rosenblum, “The Making of Presidential Administration,” Harvard Law Review 137, no. 8 (2024): 2131-2221. ↩︎

- Trump v. United States, 603 U.S. 593 (2024) (presidential immunity); Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 597 U.S. 215 (2022). ↩︎

- Arno J. Mayer, Dynamics of Counterrevolution in Europe, 1870-1956: An Analytic Framework (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1971), at p. 39 et seq. The seven typologies are: (1) pre-emptive counterrevolutions in the face of far-reaching reforms or governmental instability, (2) posterior counterrevolutions in response to an external threat or successful but contested revolution, (3) accessory counterrevolutions that aim at presumed or alleged revolutionaries, (4) disguised counterrevolutions that are internal cleavages within a revolutionary moment, (5) anticipatory counterrevolutions that those in government create as a way to crush and gain more power and (6) externally licensed or (7) externally imposed counterrevolutions in a satellite country. See Mayer, Dynamics of Counterrevolution in Europe, 1870-1956, at pp. 86-116. ↩︎

- Walden Bello, Counterrevolution: The Global Rise of the Far Right (Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing, 2019), at p. 8. ↩︎

- Marcuse, Counterrevolution and Revolt, p. 1-2. ↩︎

- I am relying here on PEW Research findings, but Thomas Piketty’s work and others confirm this. The PEW report, by Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik, and Rakesh Kochhar, finds, and shows in four graphs, that: First, “a greater share of the nation’s aggregate income is now going to upper-income households and the share going to middle- and lower-income households is falling” (Horowitz et al. at p. 15); second, “The wealth gap among upper-income families and middle- and lower-income families is sharper than the income gap and is growing more rapidly” (Horowitz et al. at p. 19); third, “The wealthiest families are also the only ones to have experienced gains in wealth in the years after the start of the Great Recession in 2007. … The wealth gap between America’s richest and poorer families more than doubled from 1989 to 2016” (Horowitz et al. at p. 21); and fourth, at the aggregate level, median wealth is down since Great Recession of 2007–08. So just imagine how bad things are for the middle and lower classes, given the increasing inequality. ↩︎

- Stuart Hall, Cultural Studies 1983: A Theoretical History (Durham, Duke University Press, 2016), at p. 23. ↩︎

- Engels, Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany, in MECW Vol. 11, p. 86. ↩︎