Confronting Words

The first prayer Jews say in the morning is called Modeh Ani after its first two words: ”Modeh anilefanecha,” it reads, “melech chai v’kayam, she’echezarta bi nishmati bchemlah, rabah emunatecha”: “I am grateful before You, the living, existent King, who returns my soul into me with mercy, great is your constancy.”

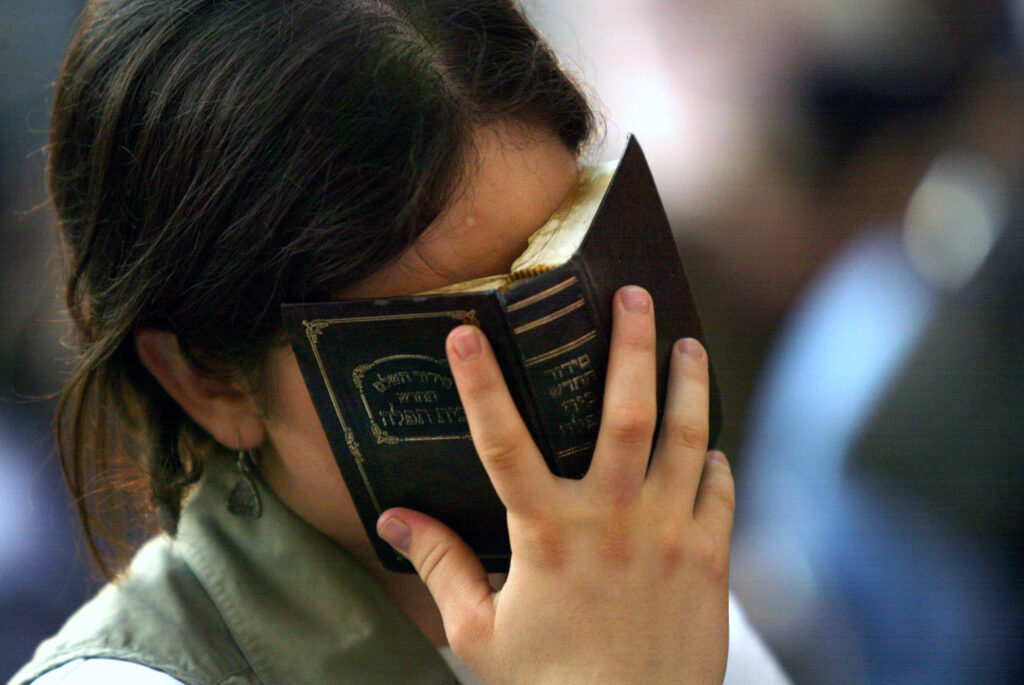

I was taught to sing these words first thing after arriving each morning at a conservative elementary day school in the undulating suburbs of west Philadelphia. That ritual, like so much of religious Jewish practice, was a method for lacing quotidian motions with spiritual significance. It was taught to me when my family and I were still members of the conservative (rather than orthodox) Jewish community. This blessing, this chant, was an early and, at that time, solitary example of the method of Jewish practice which knits meaning subtly, indirectly. I repeated the word many, many times before I began to think of what the words literally meant. I think that this is intentional, that part of the power of religious Jewish practice is that the meaning is less important than the aura it confers on daily life. I became aware of a hovering, amorphous, omnipresent presence, and this presence was connected in my mind with God. All of this was done through ritualistic chant far more effectively than it could have been if someone had simply told me explicitly in English that God returns my soul to my body each morning and I should be grateful for that.

Instead, the translation of the Hebrew words for this particular prayer had been perfunctorily read to us when we were taught the words for the first time, and it was printed on a laminated poster beneath the Hebrew lettering on the walls of my elementary school, and also on the first page of a packet of paper which all students used until our Kabbalat haSidurim — the ceremony at which I and my peers were given our first Hebrew/English prayer books. All of this ritualized interaction with the language of this prayer had facilitated my familiarization with the idea it contained — but I remember the sensation of turning the words over in my young mind and realizing suddenly what they meant. Not in English or in Hebrew but in a different sphere of knowledge, in a realm in my mind that functioned outside of language I recognized what I would now call the philosophical and theological and ontological implications of these words. Philosophy, theology, and ontology are all distinct though overlapping realms, and my religious upbringing furnished me with an unstudied worldview which provided a clumsy conception of all three. But why hand down such riches without teaching us what they mean?

When I was old enough to confront the words on their own terms, this confrontation created a tension which has only grown since. I was suddenly aware that I was expressing a condition of gratitude to the God I had heard so much about for returning my soul to my body. And this awareness had implications that inspired their own spiritual vertigo. I wasn’t sure I believed any of these implications, despite having expressed gratitude for all of them first thing each school day for as long as I could remember. And I didn’t know how to articulate the precepts even to myself, so I was helpless to search for direction from a teacher or a parent, especially since I was also inchoately conscious of a certain foreboding, a sense that this tension in me would be repulsive to my coreligionists. Nobody else seemed perturbed by the text. Nobody else seemed to struggle with its spiritual implications.

Today, with the clarity of hindsight and two decades of development, I characterize the precepts embedded in that morning prayer this way: first, I had a soul. I was not sure what this meant, but the text implied that the soul existed independent of my body. (Even now I have a marrow-deep belief in that duality, though intellectual scrutiny dissolves this certainty like ice in sun.) Second, sleep had a way of severing me such that I was split in two and this, it seemed, did not cause death. Therefore, third, the “soul” could be removed from the body without the functions of what I meant by “life” being disrupted. This last realization worried me — was I dying when I fell asleep and then being resuscitated (I lacked the language for all these questions but I still had the fear the questions inspired), and did this mean I had experienced death? But then I remembered that I had seen other people sleeping — my parents and my siblings — and they continued breathing even when absolutely asleep. Nothing so scary as “death” could be happening to us each night.

All of these concerns crescendoed into the first tempestuous instance of what became a common occupation of mine while I still lived in a religious Jewish community in which so much of my waking life was dictated by religious norms, principles, and practice: I agonized over why the faith that was either expressed outright in our texts, or implied by our behavior, was never considered directly. There were times later, while studying in the beit midrash (a Jewish hall of study) in which this anxiety swept through my body, inducing genuine vibrations, an idiosyncratic sort of panic attack. Why did we thank God every time we ate something but never spent time articulating a Jewish theology that identified God as a Being with a direct relationship to his creations, a constituent element of which involves providing them with food? Why did we spend infinite hours describing the acts that are prohibited or expected to be performed on the sabbath, but we never discussed why our God commanded this precise worship? The constant invocation of a Divine Being’s Will had inspired in me a longing to understand that Being, to look at It and scrutinize It and even to love It — which was another activity we were taught It commanded of us.

I did not know how to discuss these questions, but my religious identity was increasingly dominated by the anxiety they inspired. It struck me as false, as impossible, to feign the faith upon which our practice was predicated — but I also did not know what the faith was and so could do nothing other than pretend to have it. And this was maddening. I tried with increasing desperation to formulate for myself, in silence, without letting on to my fellow practitioners — none of whom seemed especially interested in these questions — that I had doubts. I began to spend much of my time solitarily considering the content of the Jewish texts we read and the religious stories we were told, trying to assimilate the substance of these disparate modes of traditional engagement into something resembling a world view which made up “Jewish faith”. This was, I felt sure, what a Jew such as myself was supposed to have.

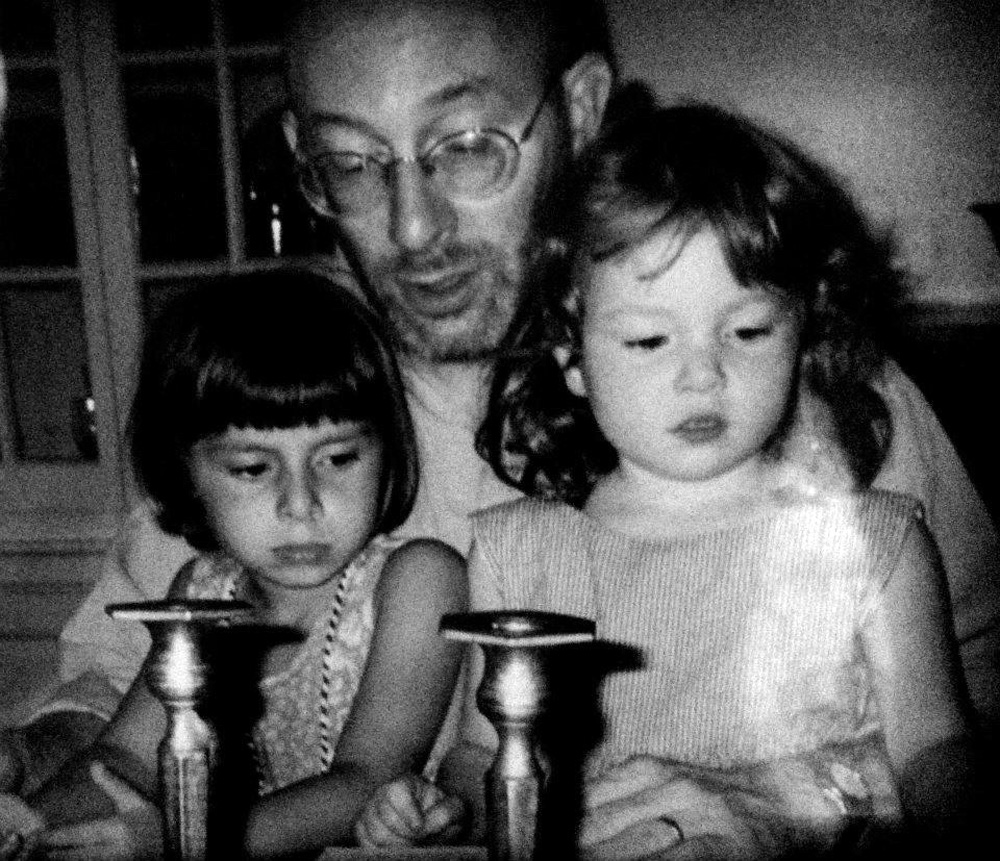

In hindsight I know this kind of inquiry was something I had learned to value from watching and listening to my father, who scavenges for nuggets of philosophical wisdom in the Jewish tradition. When I was old enough to be told about the discipline called “philosophy” my father insisted that the Jewish tradition, like the Western philosophical tradition, is engaged in the conversion of abstract principles into material decisions about how to live a life. I believed this and I repeated it when I was young but today I can see that this was a mistake: what I wanted was spiritual sustenance, which is not what a philosophical system could provide for me. (It certainly can for other people and I believe that it does for my father.)

My father represented one way of relating to the tradition and everyone else in my community represented a different one. Neither of the two paradigms felt appropriate to me. Both seemed to willfully misunderstand what the tradition seemed to want from its practitioners: to either ignore its content, or to pick and choose what it considered essential.

Of the two options, my community’s blind practice was far more distressing and alienating to me. The content of our practice engaged me in an intensely personal way, but I encountered that content first and foremost in community with others who never seemed vexed by the questions that content inspired in me. But even as I found the communal mores vexing, I also could not separate Judaism from the way the Jews around me practiced it. I could not relate to Judaism as anything other than a vehicle for the perpetuation of certain beliefs, safeguarded by perfunctory communal practice and social insularity which had, for millennia, shepherded our textual and spiritual heirlooms from one generation to the next. I saw that the beliefs were inessential to the religious community – and, even more confusing, the beliefs were incompatible with one another! From one prayer to the next within the same service the Jewish God changed shape and color.

Initially I sought refuge from that blindness by imitating the mode of engagement my father modeled. I tried to consider each text or precept in isolation, and to ignore the tensions or outright contradictions that they had with one another. I maintained that strategy until I accrued the freedom and capacity to seek out texts of other sorts: Christian, Muslim, Greek, and secular texts, which treated themes like the ones that filled our sacred liturgies. And as this became possible the early tension I had first felt as a child, between the realm of my own mind which was fascinated by the philosophical or metaphysical substance of our tradition, and the communal dimension in which the tradition was bequeathed to me intensified. The word “metaphysical” was itself a new one, one which did not seem to fit neatly into either the community’s Judaism or my father’s iteration of it. Metaphysics was not a word my father ever used when discussing Jewish thought with me — the sharp intellectual rigor of his mind eschews spiritual indulgences, but when I learned this term I applied it myself to the content I was attempting incompetently to wade through, like a toddler in a tempest.

This tension became my primary association with my own faith. It took me many years to understand that Judaism, like all religions, contains many contradictory beliefs because it bears the fingerprints of millennia of human life. It is a palimpsest – it bears the markings of how the tradition incorporated, bit by bit, whatever practice and belief its practitioners happened to be exposed to through their overbearing or kindly or disinterested neighbors in the diaspora (or the slim minority which remained or returned to the site of out of our glory and destruction in the Middle East). That is how Judaism survived all this time: through protraction, through addition, through carefully monitored but inevitable syncretic development.

I’ll give you an example. Consider the aforementioned Modeh Ani, which is how Jews across contemporary denominations begin their morning prayers. The prayer does not appear anywhere in the Bible; nor in the Talmud (the “oral law” written and then compiled in ~500 BCE); nor in the Shulchan Aruch, often called the “code of Jewish Law”. The Shulchan Aruch was, however, written by a Rabbi named Joseph Karo, in Safed, present day Israel, in 1563. And, as it happens, Moshe Ben Machir, the man who wrote the text in which the Modeh Ani prayer appears for the firsttime, lived in Safed at the same time as Karo.

Many centuries before both men flourished, the sages of the Talmud instructed that upon waking the first thing a person should say is “elohai neshama shenatata bi tehorah hi” which translates, “My God, the soul you gave within me is pure.” This prayer-formulation was moved to later in the morning liturgy sometime between the compilation of the Talmud and the present day. But before it was moved, practicing Jews heeded the Talmud’s precept and began their days with that incantation. This means that Karo and Ben Machir — two men who in no small part shaped my conception of Jewish faith, Karo because he wrote the codex which outlines religious Jewish practice, and Ben Machir because he wrote the Modeh Ani prayer which catalyzed my very first foray into considerations of metaphysics — began their days intoning that phrase. “My God, the soul you gave within me is pure.” No mention of dualism, no mention of the soul leaving the body, and an expression of gratitude for a “pure” soul. What does it mean to have a pure soul? What did Rabbi Karo think it meant? Did Ben Machir believe that his prayer was consistent with the incantation he said each morning? Did he think about that at all? Did it matter to him?

The theological weight of Modeh Ani seemed to me to evince a powerful and carefully thought through theology and ontology. Did Ben Machir intend for those words to be emblematic of a broader system of thought and faith? Would it seem nonsensical to him that someone so different from him, someone like my five year old self, was repeating it catechismically without any awareness of the enormous edifice of which that prayer was just a small building block? Were the questions that Modeh Ani inspired in me relevant at all to Ben Machir? Or was I asking the wrong questions? Does he, as the author, have more authority than I do to decide which questions matter?

Both Joseph Karo and Ben Machir were Sephardic kabbalists living as Jews through the sixteenth century. Sephardic Jews are members or descendants of the Jewish communities which developed on the Iberian Peninsula with epicenters in Spain and Portugal, where both these rabbis were either born or from where their families originated. The sixteenth century was not a particularly safe time to be Jewish anywhere, but especially not in the Iberian Peninsula. We know far more about Rabbi Joseph Karo’s life than we do about Ben Machir, so we know precisely how and why he ended up in Safed despite having been born in Toledo in 1488. At four years old, Spain expelled all of its Jews and Karo and his family fled to Portugal, where Jews were expelled five years later. The family then moved to Morocco, Nikopolis – then under Ottoman control – then to Turkey, and finally to Safed. We don’t know where Ben Machir was born but we know that at some point in his life he lived in a city bombinating with the stories and perspectives of Jews who had fled one country after another on the hunt for safety, Karo among them.

Think of the differences between me, a Jewish American female of the twenty-first century, living in a period of human history that neither of these men could have imagined, and relating to the God whose image I search for in the laws they codified and the texts they wrote. For significant periods of their lives, these two rabbis lived in the same place at the same time. The God these men prayed to offered what must have felt like very real safety and salvation. The pure soul they thanked Him for was, perhaps, the gift they believed spared them from the monarchs’ blades.

I know no such fear or faith. I practice Judaism, and I study it, and I live within it because I choose to do so. There has never before the contemporary period been any Jew like me in all of our long history, and I dedicate myself to our tradition also because I want my chapter to be included in the palimpsest. That is an honor I choose to aspire to: choice is the greatest difference between me and every other Jew living outside the bounds of modern liberalism. I choose to situate myself within the Jewish palimpsest because I recognize that it is an honor to have been bequeathed this ancient, muddled testament to the human struggle for meaning, and because I feel bound by the weight of that inheritance. When I beseech God for mercy, the God I beg is a God these rabbis would find at least as unrecognizable as they would find me. So who is the God I am speaking to, if He has nothing to do with theirs? And what does it mean for me to be a descendent of the tradition that both of these men helped to form? Ben Machir’s incantation about the soul is still the first thing I say upon waking. What does it have to do with me?

What does it mean to be a believing Jew? What does it mean to study and perpetuate the faith of my forefathers, when hardly two agreed on basic philosophical and theological principles? In practice, Judaism is whatever the Jews in a committed Jewish community do. Even the law, as various communities practice it, is differently interpreted and applied. In our day Judaism only exists within reach of secular societies, and there are many Jews who conceive of themselves as cultural Jews who do not aspire to a religious life that mandates constant sanctioning by any religious authority. Their Judaism allows for spiritually autonomy. Within orthodox Jewish communities Jews who would recognize one another as practitioners of Jewish faith do not practice Jewish law the same way – there are orthodox Sephards and orthodox Ashkenazim, and each of those communities is comprised of too many sub-groups to count. So what does it mean to be Jewish?

One way of describing the porousness of Jewish faith and the elasticity of Jewish practice is toleration. The tradition is tolerant of many different iterations of itself. This toleration was a mechanism of self defense: it is what facilitated the perpetuation of the religion. But for a young person keen to find a formula for expressing religious fervor, this laxity was maddeningly unhelpful. I was scrutinizing the text with such zeal, trying vainly to discern within it a framework for relating to the infinite. I recognize now that the appetite I was trying to sate was not philosophical at all but spiritual. I wanted God. And God was everywhere and nowhere. In our texts, in our rituals, God is constantly invoked but never concrete – every time He comes into view, every time one text expresses a theology, some other, equally authoritative document or practice offers a competing vision. What is the Jewish God? How can we love Him?

These questions gnaw, but I have learned to relish the sensation. It is tempting to conceive of religions as if they have a concrete self conception and a coherent worldview. But religions, like people, are composed of many contradictory motives yoked fibrously together. And also like people religions can only be properly appreciated when one does not see them as hypocritical if they are inconsistent, uneven, unreasonably passionate, or passionless and legalistic. It is a gift to inherit a tradition rife with overlapping meanings and nourishments. How deliciously provocative, satiating, and terrifying.

Celeste Marcus is the managing editor of Liberties Journal. Her biography of the artist Chaim Soutine will appear in October of this year.