Facial Recognitions

Earlier in the year, I attended a seminar discussion about the rising threats to social cohesion in Britain, at a time when a new media ecology, based around Instagram, YouTube, X, and TikTok, is conjuring racial resentment and helping to mobilize people behind a far-right agenda. Misinformation, racist memes, and camera phone footage of street-level violence all contribute to a feeling that society is under imminent threat from outsiders. All are being amplified by high-profile reactionary social media accounts, especially Elon Musk’s.

The discussion was attended by a number of current and former mayors of English cities and towns, including some that had experienced severe racial tensions over the past 15 years. Each spoke vividly about steps they had taken to avoid potential conflicts, which in every case drew on a timeless political craft: face-to-face conversation. Whether it be organizing neighborhood meetings, or (in the case of one mayor) personally visiting the homes of known racist rabble-rousers for a chat, getting together in person and looking people in the eye was the indispensable way of defusing potential violence and enabling separate communities to rub along.

This is scarcely news to those responsible for street-level policing and peace-keeping missions, the more enlightened of whom have long recognized the potential benefits of keeping the faces of officers free from helmets or masks. But it has attained an added urgency, at a time (especially since Covid lockdowns) when in-person communication has often come to feel like the exception, and not the default. Debates over the relative merits of CMC (computer-mediated communication) versus F2F (face-to-face) are as old as the internet, as sociologists and computer scientists grappled with the question of which aspects of F2F could and couldn’t be recreated by CMC, and vice versa. But as bandwidth has expanded and video has increasingly replaced text as the medium of online communication, many of those earlier insights have been forgotten. Throw in algorithms geared to rouse emotional reactions, and CMC (once innocently identified with email and message boards) becomes a potential driver of social unrest. There is a rising cultural and affective mismatch between community relations as imagined and represented via media, and those that are actually encountered in everyday life.

For a variety of reasons, the exposure of faces has been a feature of numerous political crises and controversies over the past decade and a half, which often have had little to do with digital interfaces. In 2010, the French government passed legislation banning the wearing of “clothing designed to conceal the face” in public, most notably niqabs (as worn by Muslim women) but also balaclavas, motorcycle helmets, and other masks. Belgium passed a similar law a year later. Following an appeal, the French law was upheld by a European court in 2014 on the basis that it “was not expressly based on the religious connotation of the clothing in question but solely on the fact that it concealed the face.” So was the Belgian law three years later.

A countervailing political tendency was exhibited by the first international Million Mask March of 2012, loosely associated with the hacktivist group Anonymous, which popularized the cartoonish Guy Fawkes mask as an icon of protest movements and anti-capitalism. In popular culture, the release of The Mandalorian (a Star Wars spin-off) in 2019, the blockbuster with which the Disney+ streaming platform announced itself, involved a hero who wrestled with his duty to never remove his full-face knight’s helmet.

The politics of the face became more fractious in the 2020s. The Covid-19 pandemic resulted in technocratic exhortations to cover the face, primarily to avoid the risk of emitting the virus via the mouth, more than of inhaling it. It was telling that Western governments reached this conclusion much later than those in East Asia (which had the precedent of SARS to learn from), insisting for several months that the virus was not airborne, which also allowed them to duck the uncomfortable political implication that mask-wearing may have to become mandatory. Many thousands of deaths later (especially of people such as bus drivers whose work involves face-to-face contact with strangers), that position was reversed.

In line with public health advice, masks were a defining visual feature of the Black Lives Matter protests that shook US cities in the summer of 2020, while being ostentatiously rejected by MAGA-aligned conservatives, who branded them “muzzles,” and linked them to the growing range of Covid-era conspiracy theories. When sick with the virus in October 2020 (and therefore a danger to those around him), President Trump performed a photo op on the White House balcony, tearing off his mask for the crowd and photographers below. For contemporary conservatives, hostility to the mask is often about its symbolic covering of the mouth, and by implication speech.

Trump’s second term has further elevated the face as a site of conflict and power dynamics. Among the concessions that Columbia University made to the White House in order to continue receiving federal research funding was that face coverings (worn by many pro-Palestinian student activists) be banned from campus. Simultaneously, US cities have experienced the terror of masked ICE agents (usually with pulled-up snoods and shades) appearing in unmarked cars to perform arrests of those they deem to be in the country illegally. In response, two Democratic Senators introduced legislation dubbed the “visible act” which would ban such practices, but it has not progressed. California has successfully passed legislation banning law enforcement officers from covering their faces, but the Trump administration has already announced that it has no jurisdiction over federal officers, such as those of ICE.

What can we read into these disparate examples? Why has the face—its presence, absence, nakedness, and concealment—come to play such a central role in political disputes and controversies today? What does it tell us about those conflicts, that this body part (if that’s what it is) features so large in them? Tracking the politics of the face leads us into contact with many of the key dimensions of twenty-first century politics and power: technologies of surveillance, questions of community membership, the limits of technocracy, the crisis of literacy, incipient fascism, and the lingering hopes of peaceful multiculturalism.

A face is many things at once. It is a part of the head, and one of the only body parts (together with the hands) that is conventionally left naked in most cultures. It is also a powerful vessel of meaning and communication, including those messages (such as anxiety or mendacity) that we may prefer not to reveal about ourselves. It has long lent itself to iconography, from the early images of Christ, through centuries of portraiture, via the cinematic close-up, to the emojis and reaction gifs of contemporary social media. It is a means of instantly knowing who someone else is. We each carry in our memories vast registers of those we have met, have seen, or recognize. Today, in the age of AI, it is also a machine-readable source of information that can be added to databases, with or without our consent.

Theories of democracy and the public sphere have typically emphasized linguistic communication, whether that be the spoken word of the ancient Greek polis or the newspapers of the bourgeois public sphere. As a result, the face as such is not granted a major political role. Hannah Arendt’s defense of the public realm admittedly placed great value on the shared visibility that it bestowed upon its participants, claiming that it was only in such a space that people could ever truly reveal themselves to one another. But this phenomenological stance never materialized in terms of the technical exposure (or otherwise) of a face or body. Politics, as the practice of rhetoric, argumentation, and critique, can go on with or without the presence of faces.

And yet the perceived crisis of the liberal public sphere, driven by the conglomerations of the “culture industry” and “mass media” in the twentieth century, or “ big tech” in the twenty-first, has often led to calls for a renewal of face-to-face civic life. This has been particularly prevalent in the United States and France, where republican political traditions celebrate an active and self-governing citizenry at both local and national levels. Nostalgic Tocquevillian laments for lost town-square democracy are features of both conservative and liberal political imaginations in the United States. Robert Putnam’s influential 2000 study Bowling Alone correlated the rise of television in the second half of the twentieth century to the decline of in-person civic participation. In early 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron sought to tackle the political alienation expressed by the gilets jaunes protests with a two-month “grand debate” tour of the country to converse with members of the public face-to-face.

Nostalgia, cultural pessimism, and moral panic all play a role here. But the search for an affirmative theory of face-to-face contact has more often led toward ethical rather than political philosophy, specifically that of the French existentialist Emmanuel Levinas. For him, it is in the “face of the other” that we experience an infinite moral demand, at the heart of which is the simple injunction “do not kill me.” “The human being in his face is the most naked; nakedness itself,” he argued. “The face looks at me, calls out to me. It claims me.”1 Departing from the lonely introspection that had characterized previous existentialist philosophies, in which other people are a source of irritating chatter or worse, Levinas discovered in the “face of the other” the appearance of a universal humanity that cannot be denied. This face is prior to culture and language, containing a force that is irreducible to body language or physiology, or indeed to politics. It is a basic fact of being human.

Levinas’s ideas have been mobilized in the service of Western republican ideals, to provide philosophical ballast for such policies as the French face-covering ban. Some scholars have pushed back against this, arguing that those (such as the French communist politician André Gerin) who applied Levinas in this way were mistaking an ontological argument for an empirical one, that is, treating the “face” in an overly literal and bodily sense. There is no doubt that Levinas’s priority was to understand the obligations that we unavoidably have toward others, and not the obligations they have toward us (such as that to remove a veil, to fit in with “our” customs).

Where Levinas’s ideas have greater purchase is the facial politics of Covid-19. The virus resulted in the mass adoption of face-coverings, but its more profound impact was in generating a wholesale crisis of hospitality in which “the other” was avoided, distrusted, and debarred, and all public interaction was—for a while—digitally interfaced. At every turn, “the other” became a risk and a threat. Far from interrupting conviviality, the masks worn by protesters in the summer of 2020 actively resuscitated it.

The notion that democracy, community, or a republic can be saved if only masks, veils, and screens can be abandoned has an understandable draw on our emotions, often as part of a wider nostalgic yearning for something that feels lost. It is frequently tied up with inhibitions about modernity more generally, a symptom of what generations of classical sociologists have termed “disembedding” or a shift from Gemeinschaft (community) to Gesellschaft (society). Something has cut us off from one another, and therefore that something has to be punctured or banned, so that we can achieve political and cultural intimacy once more. To some extent, the twenty-first century politics of the face is another episode in this dance of technological progress and romantic regress. But this dialectic, in which the exposed face is somehow resistant to alienation, individualism, or technocracy, misses the historically distinctive ways in which the face is instrumentalized today.

During the same decade when European policymakers and judges were grappling with the rights and wrongs of face-coverings, facial recognition and analytics technologies were advancing at pace, thanks to machine-learning algorithms trained upon billions of photographs. “Affective AI” technologies promised to unlock secrets of consumer sentiment by analyzing facial expression, while individual identification was reaching a level of accuracy (though far from 100%) and facial recognition was embedded in some CCTV camera networks in London in 2016, without public consultation or discussion.

Ironically, given the masking that accompanied it, Covid-19 hastened the advance of facial recognition software, which could be sold as a basis for more hygienic, contactless transactions of various kinds. Today, facial recognition and analytics are ubiquitous: at national borders, in mobile police vans, as biometrics to prove identity or age, as means of combating shoplifting, and so on. The exposed face has become a means of payment and safe passage, and equally a possible denial of those things. Among the political threats these technologies pose is that of racial bias, and an apparent weakness when it comes to analyzing and recognizing black faces.

This infrastructure performs a basic principle of modern surveillance, most famously examined in Michel Foucault’s account of “panopticism”: political modernity reverses the direction of visibility and identification away from the spectacle of the powerful and toward the behavior of the powerless. As individuals become more exposed to surveillance—and therefore more classifiable—so power disappears from view. The politics of masking that has reverberated in Trump’s second term is a case in point: the banning of masks among Columbia students is of a piece with the fearsome visual anonymity of ICE agents, defended by the Trump administration on the basis that these agents are vulnerable to being doxed. Who gets to mask and who doesn’t is a basic index of political hierarchy in an age of ubiquitous videography and facial recognition. By this same logic, the adoption of masks by protesters is not only self-interested (though it may be that, when they’re exposed to the threat of prosecution or punishment) but a means of dissolving their identities into a collective bloc, with aspirations to power.

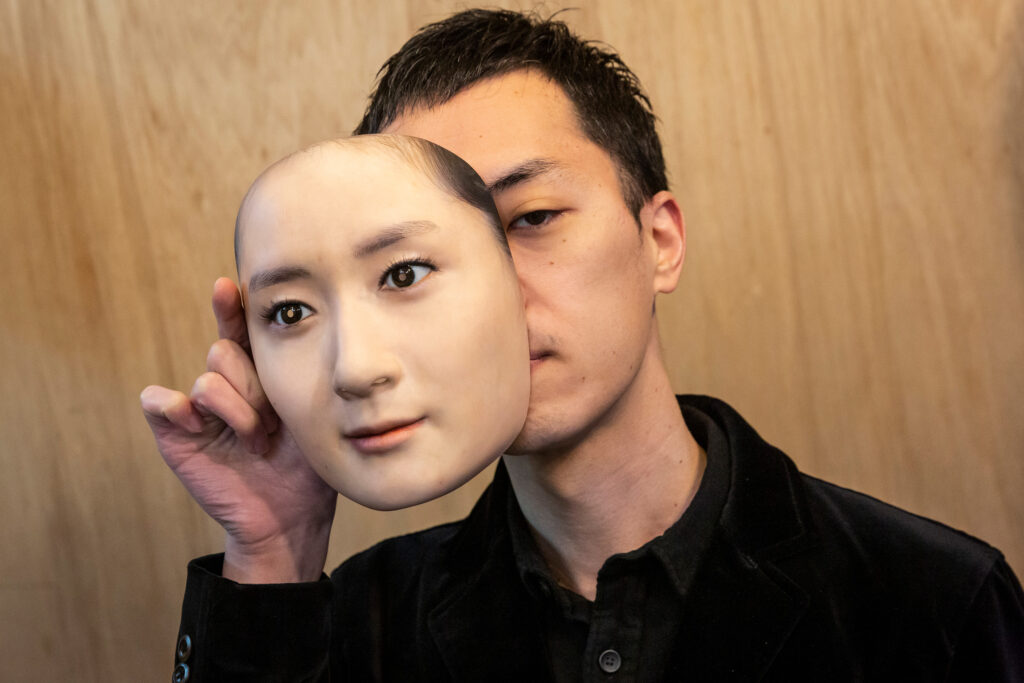

Under these technological and political conditions, the face becomes akin to a name or number, a substitute for the papers that had to be shown to officials during the highpoint of bureaucratic power. This exemplifies what Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guatarri termed “faciality,” whereby the face is constantly being endowed with forms of significance that are political and historical in nature. By this account, there is no getting around the politicized face, in search of some pre-political, pre-conceptual face, of the sort that was the basis of Levinas’s ethics or the romantically imagined republican community. The face becomes the official public image of the underlying legal subject, and covering it up becomes a juridical—potentially criminal—matter.

Yet it is not just the authorities that have made the face into a central political instrument. The digital public sphere produces torrents of video and textual content to be sifted by human and non-human recommendations, producing hierarchies of virality. The face holds a privileged position in this babble as an icon that can hold its form in a maelstrom of noise and a gale of shifting contexts and misunderstandings. The prominence of reaction videos and reaction channels (which focus on the split-second moment when someone experiences a surprise, a piece of music for the first time, a prank, or whatever) centers upon the face as a source of truth and a measure of value. Emojis, smile/frown feedback buttons, and reaction gifs codify facial expression. And with short-form video, now devouring all other media formats, visual emoting steadily replaces arguing, while empathizing replaces listening.

At the same time that the face has become a piece of machine-readable information, the public sphere has been undergoing its own shift from a culture of literacy to one of faciality. On a technological level, this is a function of smartphone-based culture. But the valorization of the face is also of a piece with a culture of immediacy, which strives for hidden, underlying meaning as an escape from an over-abundance of information and signs. As Deleuze noted of the cinematic close-up, facial presence on screen holds out the promise of depth, authenticity, and meaning, an escape from fakery and hubbub. But this kind of hunt for reality cannot ultimately get around the fact that, as Deleuze stressed, the face is always already overloaded with significance and symbolism. Our digital culture of faciality is partly a response to a sense that words (especially those of politicians and journalists) are designed to deceive, which merely shifts even-greater symbolic weight onto faces.

2010 was a key year in the formation of this new facial regime. It was then that smartphone culture became hegemonic and when the first iPhone with a front-facing camera (the iPhone 4) was launched, formalizing the conventions of the selfie and the video essay. On October 6 of that year, Instagram was launched. The very next day, the French face-covering ban was declared constitutionally valid by the Constitutional Council of France, clearing the way for its legislation and enforcement. A combination of republican and digital logics inaugurated the face as the basis of governable identity and citizenship.

There is something exhausting, not to mention potentially oppressive, about this kind of regime, which has bizarre side-effects, such as 11-year-olds developing obsessive skincare regimes that were once associated with anti-ageing. Sociologists who have studied everyday emotional labor, such as Arlie Russell Hochschild, have long understood that behaviors such as smiling can be a form of work. What might look like surliness or disaffection might equally be a refusal to participate in norms of facial communication—what in the hands of a musician might be classed as “cool.” The ethnographer Erving Goffman spent considerable time studying mental asylums in the 1960s, noting that the failure of patients to appear fully “present” might be considered a form of alienation from the institution at large.2 In micro-managed situations, the blank stare has long been a mode of resistance.

Disputes over who does and doesn’t have an obligation to reveal their faces, what facial expressions do and don’t mean, have become endemic to our political culture. But they are invariably about something else altogether: membership of a community, accountability, power, and evidence. Societies of blanket surveillance and ubiquitous videography and screens have integrated the face into far-reaching networks of political discourse, technology, and violence. Who gets to absent themselves from those networks, and on what terms, and who does not, is now a crucial index of political hierarchy.

William Davies is a Professor of Political Economy at Goldsmiths, University of London. His writing is available at Williamdavies.blog