The Economics of Complicity

How Israel Is Buying the Destruction of Gaza

Hamas’s attacks on October 7, 2023, have changed many things in Israel. Among the most worrisome developments since then has been the near disappearance of people’s resistance to some of the worst excesses of Benjamin Netanyahu’s administration.

For some months before the attacks, an unprecedented number of Israeli reservists had been refusing to serve in the military, part of a popular protest against the government’s threats to overhaul the judiciary and dismantle the country’s democratic institutions. Military reservists, who form the backbone of Israel’s defense establishment, were leading this resistance. Thousands had declared their unwillingness to serve under the ultra-right-wing government and what they saw as an increasingly authoritarian regime. Senior military officers, veterans of elite units, and Air Force pilots announced that they would refuse orders. It was the most serious crisis of military insubordination of the last several decades.

The movement represented not merely political opposition to authority but a fundamental challenge to the automatic compliance that had long characterized Israel’s pervasive military culture. From a social perspective, this was a particularly compelling phenomenon, with the politicization of a broad swath of the public around legal and political issues that are often overlooked.

But after October 7, the very same pilots who on principle had refused to take orders now began carrying out a strategic bombing campaign targeting a largely unprotected civilian Palestinian population. In effect, they agreed to execute Netanyahu’s directive to turn Gaza into “rubble.” Within days, and then for weeks and months, tens of thousands of Israelis actively supported, or participated in, military operations that amount to some of the most severe violations of international humanitarian law in recent history. The brutality of the war and the use of starvation as a weapon, among other things, have led multiple researchers and organizations to conclude that Israel is committing war crimes and crimes against humanity, as well as a genocide, in Gaza.

Yes, there have been protests against the government’s campaign, and yes, some reservists—several hundred, we estimate—are refusing to serve, at the risk of a prison term. But the military reports having no problem carrying out its missions because of noncompliance. According to a poll conducted in March by Tamir Sorek, a professor of Middle East history at Pennsylvania State University, 82% of Jewish Israelis surveyed supported expelling all Palestinians from Gaza (and 56% favored expelling Arab citizens of Israel). General acceptance of the military’s mission has been maintained, in other words, despite both the growing scale of the government’s crimes against Palestinians and its continued onslaught against Israel’s democratic institutions.

No doubt, the attacks of October 7—and their cruelty—and Hamas’s other crimes since have traumatized Israelis; the notion that the State of Israel was a safe place for Jews has been shattered. But the dramatic transformation of many people’s position from resistance to a form of tacit compliance also demands a fuller explanation.

A New Currency

How does a democratic society move so rapidly from unprecedented protest to silence and arguably, in some cases, to moral, or even actual, complicity in state crimes? In our book The Lexicon of Brutality: Key Terms from the Gaza War (Pardes, 2025), we examined the discursive mechanisms that have enabled public support for the war, and so, too, the crimes being committed in Gaza: the linguistic and cultural tools that normalize the unthinkable and make mass atrocities socially acceptable. Consider, for example, the use of euphemisms or terms that obfuscate harsh realities, like “strategic bombings” and “humanitarian zones,” or the notion that “there are no uninvolved in Gaza.” These ploys implicate the public in state violence even as they facilitate the implementation of government policy. They create what we call “a cage of discourse” by confining thought and restricting the space for dissent. In times of war, many nations rally round the flag—with the result of building up public support for engaging in violent conflict. But the discourse in Israel since October 7, 2023, has also provided legitimacy for a wide variety of crimes: we argue in our book that it has become a main pillar for the government’s attempt to create a criminal society.

Such was for our argument about the discursive mechanisms the Israeli government deploys. However, that cage does not operate on its own; it is supported by a second, powerful economic mechanism.

The Netanyahu administration has transformed military service to offer material incentives that purchase not mere compliance with, but also active participation in, atrocities. It has created a war economy that binds the welfare of several hundred thousand Israelis to state-committed crimes, thanks to a tool that is both simple and effective. A new economic currency has emerged in Israel during the Gaza war: the “reserve duty day” (RDD), the state’s remuneration for a day of reserve service.

The Israeli government commits to paying individual reservists almost 29,000 Israeli shekels (close to $8,800) per month to volunteer for reserve duty. Minimum wage in Israel is 6,247 shekels (about $1,890) per month, and the average salary across all sectors is 14,200 shekels (about $4,300). The RDD thus offers more than 4.5 times the minimum wage and more than double the national average. It is competitive with tech salaries, long the gold standard of prestige employment in Israel.

The RDD is not merely payment for work over a given unit of time: it is an attempt by the state to purchase the active partnership of citizens in its project to annihilate the Gaza Strip. This is not an entirely new mechanism. A large part of Israeli society (mainly Jewish men aged 21–45) has long been formally assigned to a military reserve unit and could be summoned to service—separated from their daily job, their family, their routine—with compensation. But before October 7, the use of RDD was limited to a maximum of 42 days annually (and the actual average was about 11 days). Reserve service was seen as a genuine civic obligation, and it imposed a relatively small financial burden on the Israeli economy overall. From 2018 to 2023, according to the Israeli Democracy Institute, reserve-duty time amounted to no more than 0.1% of total working hours for the entire labor force.

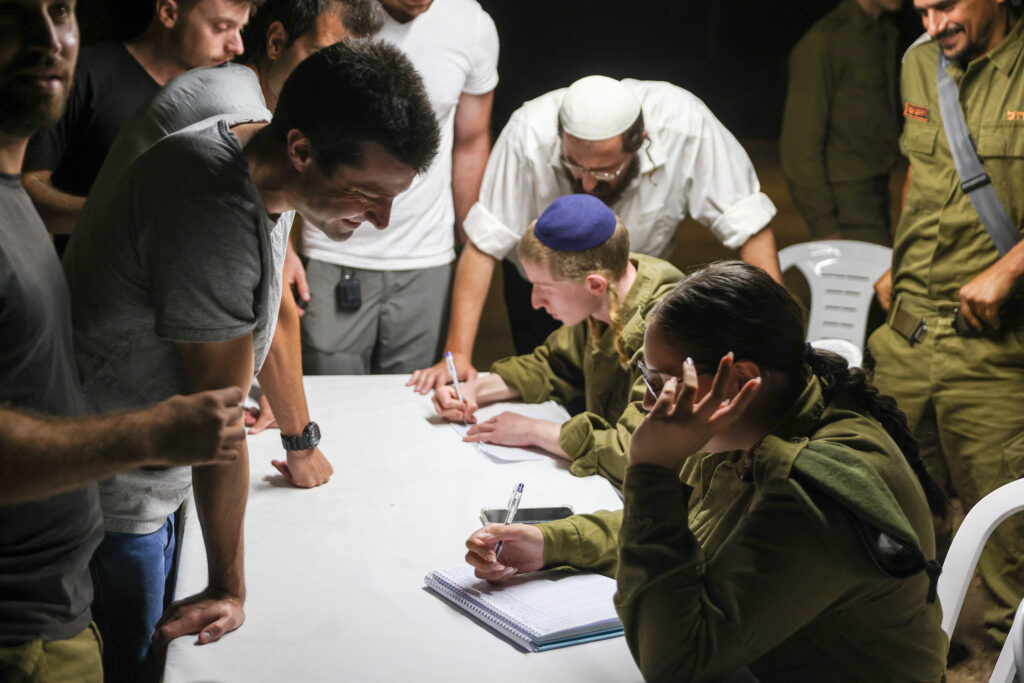

Today, though, the scale of military service is unprecedented: according to Israel Defense Forces data, in 2024 some 300,000 reservists participated in an average period of service of 120 days. To deal with this huge number and its toll on both reservists and their families, the army has introduced what it calls “open orders,” allowing reservists to work minimal hours for the military while receiving compensation for both their military service and their daily civilian job. The state has also introduced additional bonuses and social services for reservists, as extra compensation for longer service spells.

The RDD is, in essence, a public bribe to encourage private individuals to enroll in Israel’s military gig economy. This is a significant innovation in modern warfare economics, considering that the Israeli army has historically been a people’s army, with no mercenaries; it is a systematic way of purchasing citizens’ compliance through a sophisticated design of freelance work. An article in the Israeli economic daily The Marker exposed “a whole world of WhatsApp groups where people seek to do reserve duty.” The open-order system allows reservists to effectively double-dip by maintaining partial civilian employment while receiving full military compensation.

It’s a very flexible arrangement, too. One 34-year-old reservist described to The Marker how soldiers he knows used RDDs to pay for various goods and services—in this case, meat for their unit’s barbecues: they simply registered their butcher as a reservist entitled to 30 days of reserve pay. “A parallel economy has developed here,” the reservist said, with RDDs functioning as a recognized currency. The gig model has extended beyond traditional employment relationships to create new forms of economic participation.

A growing network of interests is capturing more and more segments of the population, as each additional participant increases the reach and the value of the system, deepening collective involvement in government policies. Active reservists represent about 16% of the relevant population (meaning, mostly Jewish males aged 21–45, minus the ultra-Orthodox, who do not do military service). Today, many of them still serve for long periods and are directly enrolled in the war economy. Their extended social networks encompass a much larger share of Israeli society.

Incentive as Control

This economic transformation functions as both an incentive for individuals and a means of control for the government. In return for the compensation it gives out, the state receives far more than just military labor to execute its policies; it also acquires partnership, support, and social legitimacy. The RDD functions as currency and contract, creating an economic bond that ties an individual’s welfare to the state’s military operations, even if those involve crimes. And so here is an economic cage, on top of the discursive one—together, the two trap Israeli society by incentivizing it to follow the government’s political designs, in this case for the destruction of Gaza.

Some critics in Israel have argued that the deployment of reserves appears to be inefficient, that the army command is using the RDD and open-order mechanisms without any rational planning. We think instead that this is not a bug, but a deliberate feature of co-optation. It represents an integral component of a political strategy designed to deepen civilian involvement in military operations. The mechanism of recruiting public participation through purchased labor serves multiple functions simultaneously. It provides manpower, creates economic dependence, and generates social complicity in systematic state crimes. The broader the participation, the wider the human network of material interests invested in the commission of those crimes.

The psychological and social dimensions of this economic cage are equally important. The reservist earning high monthly wages will find it difficult to criticize the crimes they participate in or witness. Their family, benefiting from a stable and respectable income during a time of economic uncertainty, will also have weaker motivations to oppose military operations, even if those involve systematic atrocities. Friends will be less inclined to criticize those sacrificing their personal life even as they profit from it. The social circles of each reservist—family, friends, colleagues, neighbors—become indirect stakeholders in the war economy. This creates a web of complicity that extends far beyond direct military participation to encompass entire communities whose economic welfare depends on the continuation of the military’s activities.

And the RDD is only one component of a broader war economy that Israel has built during the Gaza conflict. Additional economic incentives include extras for extended periods of reserve service (a 10%–20% bonus on base pay per day of service above 60 days annually), free psychological treatment, complimentary healthcare, and free vacations at various Israeli resorts. The system also includes private contractors, for example those hired to destroy civilian infrastructure in Gaza.

According to the BBC, Israeli bulldozer and excavator operators earn premium rates for these activities, with contractors compensated up to $1,500 for every house destroyed in the Gaza Strip. Rabbi Avraham Zarbiv, nicknamed “the Jabaliya Flattener,” represents a new category of war-crimes entrepreneurs: demolition contractors. These relationships extend the economic model beyond traditional military service, creating additional constituencies with direct financial interests in the continuation of armed operations while expanding the social network of those who profit from systematic destruction.

The effectiveness of this economic cage relies on the protracted erosion of other opportunities and the systematic dismantling of the welfare state. The war has devastated key economic sectors while creating a climate of uncertainty that discourages private investment and employment. The scale of this destruction is substantial and is expressed in a recession in leading sectors, including high-tech, and in the large number of those workers or academics who have left the country for long-term relocations since October 7. Meanwhile, credit-rating agencies such as Moody’s have downgraded Israel’s sovereign debt. The Israeli welfare state has continued to crumble, and education and healthcare expenses now consume growing portions of household budgets. In this changing economic environment, the Israeli state’s new gig-like form of military Keynesianism provides a crucial compensation mechanism, the difference between economic stability and financial distress, especially for those groups that have been harmed by decades of neoliberal policies.

Our preliminary analysis of data from the Bank of Israel reveals that as Israeli exports drastically decline and large parts of the labor force are enlisted (and therefore unable to contribute to production), fiscal spending by the government is fueling household consumption. Thus, the RDD serves not only social, psychological, and micro-economic functions; it also has a macro-economic purpose by supporting Israel’s economic growth despite the ongoing war. That, in turn, is of crucial importance to Israel’s position in the global economy, and an attempt to shield it from sanction by international rating agencies and lenders.

Meanwhile, as traditional employment becomes more precarious, military service appears increasingly attractive, regardless of its potential criminal dimensions. Reserve duty becomes what the sociologist Noa Lavie describes as “a successful gig with social prestige.” It is economically viable and socially respectable in ways that address both material and status concerns even as it normalizes participation in state crimes. Any criticism of military operations becomes a criticism of friends, neighbors, and family members who participate in and profit from them.

The broader implications for Israeli society are profound. The traditional citizen-soldier model maintained clear distinctions between the civilian and the military spheres; military service was a civic duty, not a gig. When some of the most attractive economic opportunities in a society exist within military structures, and when military operations generate the income necessary for middle-class stability, the boundary between civilian and military dissolves. And when military operations then involve war crimes and other crimes, society becomes structurally invested in the military’s criminal policies. The hundreds of thousands of Israelis now directly dependent on this system, as well as on the broader social networks they represent, constitute a powerful constituency for the continuation of the Israeli government’s policies in Gaza regardless of these policies’ strategic effectiveness, any moral considerations about them, or international legal obligations.

Complicity and the Social Contract

This transformation’s long-term implications extend far beyond the current conflict: more than a temporary wartime adjustment, it could represent a permanent shift in the social contract between the Israeli state and its citizens. And it raises fundamental questions about the sustainability of democratic governance when substantial portions of the population have a direct economic interest in the perpetuation of war crimes and other abuses.

At its worst, this development could spell the unification of Israeli society through crime. That would be both a sociological phenomenon and a political reality—the birthing of a collective mentality that politicians can act upon. Of course, members of Israeli society differ in values, beliefs, and political views. But crime has now imposed itself upon them, and through economic (and discursive) mechanisms, it has unified them. The RDD is just one of those mechanisms—and it is hardly an accidental byproduct of war; instead, it has been intentionally cultivated by parts of the leadership.

This is not the first time the Israeli government has used economic incentives to recruit citizens into criminal activity. During the Nakba in 1948, after the expulsion and flight of more than 750,000 Palestinians, the Israeli state redistributed the Palestinian lands and homes it seized to bribe a young Israeli society. One of us, Adam, wrote in his book Loot: How Israel Stole Palestinian Property (2024) that an “integral part of the Israeli public participated in the plunder” and that “This made the pillagers into partners in crime, stakeholders in the non-return of the Arabs, and involuntary supporters of a specific political policy.” Most Israelis still deny this.

Nor is Israel alone in rallying public support for criminal state policies through economic incentives. In Hitler’s Beneficiaries: How the Nazis Bought the German People (2007), Götz Aly demonstrates how the role of economics was at least as significant as that of ideology in Nazi Germany. The plunder of Jewish possessions enabled the Nazis to systematically enhance standards of living for ordinary Germans, and Germans reaped material advantages daily from the exclusion of Jews from society. Similarly, Ümit Kurt writes in The Armenians of Aintab: The Economics of Genocide in an Ottoman Province (2021) that “The fate of the abandoned properties in Aintab proves that the transfer of wealth in the form of plunder as well as expropriation was an inextricable part of the genocidal process.”

Israeli society is not inherently criminal: the crimes of the current government in Gaza that we are denouncing are neither a natural byproduct of Israel’s formation nor an integral part of Zionist ideology. But like Turks or Germans in the early twentieth century, Israelis today are being manipulated by what the historian Mary Fulbrook called “processes” of complicity in her book about Nazi Germany, Bystander Society (2023). The Israeli government is not only destroying Gaza. Through the RDD mechanism, it is fundamentally altering the country’s economy and society. It is creating a financial dependence on the state’s commission of crimes that may prove irreversible long after the current conflict ends.

Assaf Bondy is a labor sociologist at the University of Bristol who researches the political economy of employment relations.

Adam Raz is a human rights researcher and historian. He works at Akevot Institute for Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Research and is the author of Loot: How Israel Stole Palestinian Property.