Thirty Yards from Revolution

I live in a neighborhood full of magpies. When I first arrived, they would pull back when they saw the dog and me. They were wary. But over time they got used to us. Now when the dog and I pass, they set aside whatever they’re doing and take tiny jumps, moving their long tails in a language I can hardly fathom, looking around with their intense gaze. The Merlin Bird ID app can detect the sound of their warble and identify their species—Eurasian magpie—but not what they’re actually saying. As we pass by and say hello, I sometimes get a sense that they know something we don’t. It seems that they’re judging us, warning us.

Greg Grandin might’ve had a similar experience in mind when, in the introduction of his monumental new book America América, he writes that in the Western Hemisphere “Latin America gave the United States what other empires… lacked: its own magpie, an irrepressible critic.” The author sees in this critical dynamic between America and América an “immanent critique” in which Latin America denounces the United States for not living up to its own professed values—a critique that has functioned as the engine of the hemisphere’s history for over three centuries.

The book is ambitious. The discussion about Sepúlveda and Las Casas’ efforts during the sixteenth century to make sense of what the hell Europeans were doing in América could be a book in itself—if anything, because their extremely different versions of humanism informed ideas of sovereignty, rights, and hierarchies across the hemisphere. Another book could cover the foundations of Anglo-Saxon colonialism, expressed by one of the organizers of the Mayflower voyage as the right of the settlers “to take a land which none useth, and make use of it.” Instead, Grandin wrote a book about both colonialisms, their evolution over the following centuries, their entanglement with the social, political, and economic forces that grew along, how they mutually shaped each other, and the ways in which they contribute to the (rather disastrous) world in which we live today.

Grandin doesn’t merely succeed in explaining how “the magpie rivalry” between America and América “played a vital role in the creation of the modern world.” He does so through 700 pages of highly engaging writing that few historians (or writers for that matter) could achieve, a style that is intrinsic to the narrative he tells. Every story, process, official document, and individual life by which he weaves his great tapestry is fascinating. The thousand vignettes of the Americas’ history illuminate an evolving system of governance without losing the sparkle of the real life in which these stories were embedded.

When my daughter was three, I explained to her the idea of communism that her grandfather had fought for. It was, I told her, a vision of a world in which there would be candies for everybody—and nobody would have too many. Imagine the surprise of recognition, then, when a decade later I read on page 478 of Grandin’s book the slogan of Ramón Grau San Martín’s Cuban presidential campaign in 1944: “In my government there will be candy for everyone.” These reformist dreams of equality and fairness were cut short by US-sponsored reactionary politics, first by the ballot box then by the heel of a boot, making the Cuban Revolution that my daughter’s grandfather embraced all but inevitable. The story underlines both the critical dynamic of America, América as well as the irresistible appeal of Grandin’s narration.

One reads the book as if we didn’t know how it ends. And in a way, we don’t.

The decisive argument of the book is that throughout history Latin America has represented a comprehensive idea of political order in which society would collectively realize the ideals of freedom and equality for all. Anglo-America, by contrast, embraced a more restrictive vision of liberal politics and an almost paranoid view of the challenges posed by radical democracy. Towards the end of the book, Grandin suggests that the difference between America and América might lie in their origins: a moral crisis early on in the Spanish conquest compared to a lengthy evasion and denial as hallmarks of English settlement. Spanish America achieved independence from Spain understanding it as emancipation from all forms of oppression. But Anglo-Saxon American settlers didn’t fully face a moral crisis over slavery until the nineteenth century. And when the reckoning came, it did so in a way that obscured instead of illuminated other forms of barbarism and oppression that would continue to shape US society.

The book’s second overarching argument is that the most virtuous moments in the history of US liberalism were intimately connected with its Southern magpie. Bolivar’s América and the Monroe Doctrine, the Mexican Revolution and the New Deal, the seeds for an international order based on the principles of non-intervention, the hemispheric rearrangements to fight fascism—at every turn, Latin America was a laboratory of democratic politics that challenged restrictive views of political sovereignty and social change, forcing the US to reckon with the shortcomings of their Americanism. (Grandin first explored these arguments two decades ago in “Your Americanism and Mine” and “Off the Beach: The U.S., Latin America and the Cold War”—articles he has now developed into a comprehensive historical account.)

“Mexico,” the clear-eyed US ambassador, Josephus Daniels, once said, “is a laboratory for new economic and legislative ideas, most of which I regard as very good.” He was a diplomat who once even suggested in the 1930s to his boss President Roosevelt that the US might “care to copy Mexico’s radical constitution…Mexico is looking to do more for the forgotten man than you have been able to do.” For the most part, Roosevelt shared his ambassador’s outlook of the Mexican Revolution and, against the pressure of US companies, let Mexican President Cárdenas go ahead with the expropriation of the oil companies pretty much unobstructed.

But that wasn’t the rule. More commonly, the US exacerbated social conflict in the region, testing instruments of political control and economic liberalization. American elites backed the mercenary William Walker’s military incursion into Nicaragua in order to restore slavery in 1865; the government supported US companies’ competition with Europe to fuel militarization in the region (a third of all loans to the region in the years after World War I were spent on arms); American salesmen backed by the government furnished police forces and paramilitary groups with military weapons and training. After exacerbating regional conflicts, presidents like Theodore Roosevelt and officials in his administration routinely zoomorphized Latin American leaders: an “unspeakable, villainous little monkey” here, an “unspeakable carrion” there, “contemptible little creatures” everywhere. The Cold War codified the centuries-old American obsession with social order by providing local elites with the military, economic, and rhetorical resources to contain, suppress, or reverse struggles over wealth redistribution and political rights.

“Work, bread and a decent home” encapsulated, in the words of Daniels, the aims of the Mexican Revolution. The dreams of regional progressive forces were variations of the same ideas. But even that little was too much.

Few moments in the region’s history capture this political project of fused social and political rights better than the democratic transitions that emerged in the 1980s after decades of US-sponsored state terrorism. The generations involved in that process, myself included, embraced the mindset that Grandin rightly locates in the origins of the nation states, a project in which independence, political sovereignty, and material realizations coalesced into a unified vision of the democratic republic.

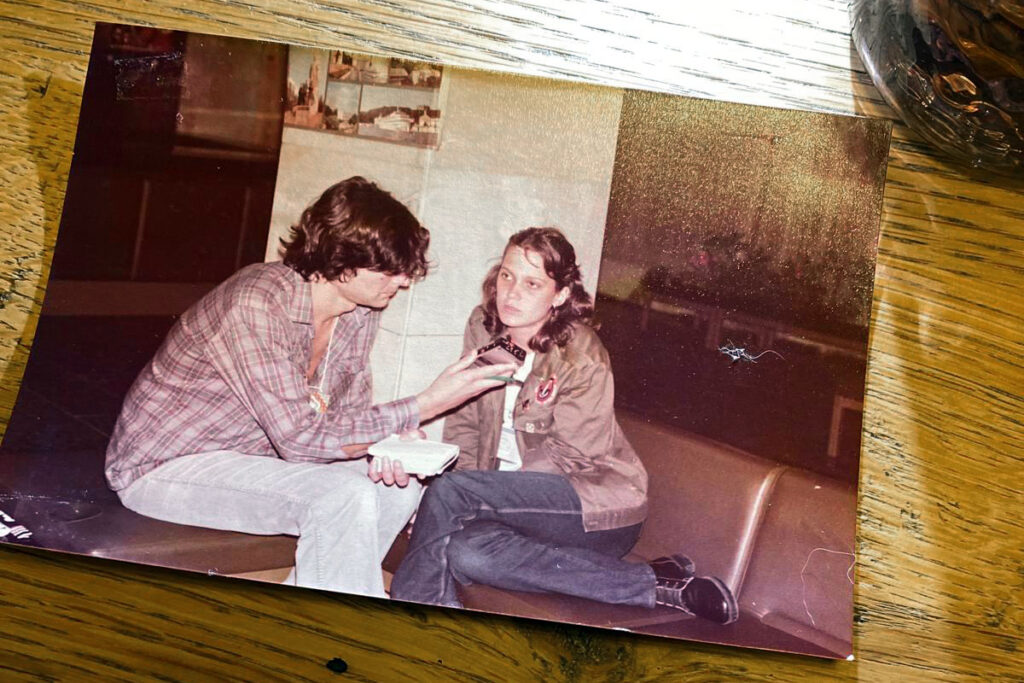

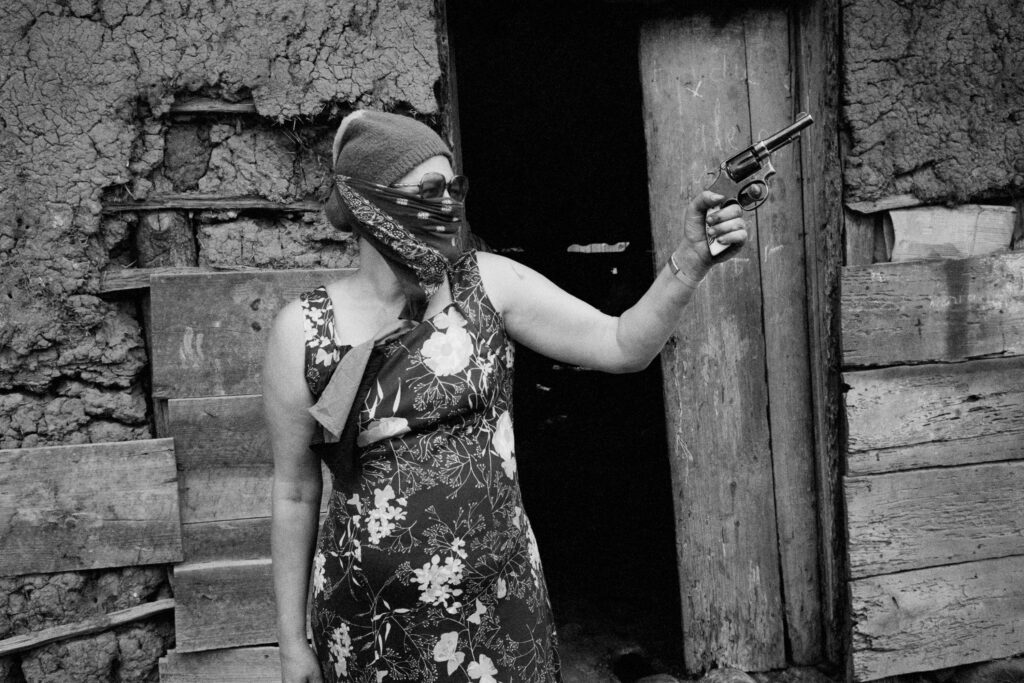

But our generation’s attachment to liberal democracy as the best way to achieve those republican ideals was not the whole story; part of our heart was somewhere else. I still remember in Moscow, August 1985, when groups of young activists from Latin America’s left and social democratic parties, some of them officials and representatives in parliaments, walked down Nikolskaya Street behind the GUM department stores on Red Square, following with deep devotion Josefina Vigil, whom we called Comandante Josefina Vigil, then 21 years old and a prominent member of the Sandinista National Liberation Front. She, like us, had joined tens of thousands of activists from all over the world to take part in the XII International Festival of Youth and Students.

We embodied a convoluted mix of ideology and hormones, Josefina Vigil was our Tania, but we also knew the Sandinistas had blown up the former Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza’s motorcade when he was in exile in Paraguay, and we venerated the activists involved in the attack. A young economic advisor of Argentine President Raúl Alfonsín followed the macroeconomic rules of an indebted country under rising inflation, but in his living room you wouldn’t find a picture of James Baker or Paul Volcker but of Fidel Castro, military fatigues and all. Future President of Uruguay José Mujica was a few months out of jail after an ordeal of more than a decade in Uruguay. Around the same time, the Brazilian dictatorship came to a negotiated end. In our countries, we did our best to reconcile revolutionary fantasies with the less fashionable tasks of slow economic reform and legal prosecution of human rights violations committed during the dictatorships. The region descended into neoliberal barbarism after those promises proved volatile.

Then, two things happened a year after we returned from Moscow. The Communist-controlled Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front (FPMR) concluded that only an arms-backed popular uprising would put an end to Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile. By mid-1986, they organized, in concert with Cuban intelligence, the largest arm smuggling in the region’s history, eventually moving 70 tons of weapons into Chile through Carrizal Bajo harbor. But the operation collapsed when a regular police inspection discovered the weapons of some activists disguised as fishermen. On September 7, another unit of the FPMR ambushed Pinochet’s armored car on his way back to Santiago from his weekend retreat in El Melocotón. In a battle that lasted just six minutes, the unit launched grenades and rockets with M72 Law, American anti-armor. One of the rockets hit the bulletproof window of the dictator’s car and bounced back on the street, unexploded. One of the explanations for this was that these rockets needed a certain distance to gather speed and explode on impact. A report by the Chilean Army later suggested that the rocket was launched from twenty yards: had it been launched from fifty, the car would have blown up in the air and Pinochet would have met the same fate as Somoza five years earlier. Was Latin America thirty yards shy from revolution?

There is no room for counterfactual history; here is what actually happened. With Cuba still robust, the first half of the 1980s saw Castro exerting influence on the region’s left, the Sandinistas were still resisting the US-backed contras, and the Salvadorean guerrillas of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front were extending their revolutionary war throughout El Salvador. The Guatemalan sociologist Edelberto Torres Rivas once pondered why the democratic transitions started during these “years of revolution and social conflicts, taking place along the most radical methods.”

Torres Rivas’ reflections on Central America loom over the rest of the region. Embedded in the narrative of America América there is a theory of civil society that potentially answers this question. The establishment of liberal electoral systems and the embrace of moderate political projects that grounded the democratic transitions in the region was not overdetermined but the result of the remarkable effort of individuals and societies historically situated. I’ve always marveled at why, after years of state terrorism and when most of those accused of human rights violations roamed free, people didn’t just go and put a bullet in the head of those who had raped, tortured, and killed our loved ones. But they didn’t. Instead, people joined human rights organizations. They became members of political parties and exerted pressure over parliaments. They ran for office. They rallied in the streets. They sued criminals in lengthy processes through archaic judicial systems, many times still influenced by the very perpetrators of state terrorism. They litigated in international tribunals and learned about similar cases in other parts of the world. They opted out of violence and collectively bet on the boring and frustrating way forward. And in doing so, they helped to build robust civic principles and a more humane world.

But I digress. The point is that, as a historical construct, the story of Latin American democratic transitions reveals both the defeat of more radical alternatives and the unyielding project of achieving a fairer world. And a larger historical point related to America América emerges from this detour. The lesson Latin America offers from its centuries of struggle is not only that of the magpie of American liberalism. Many times, revolutionary political violence was embraced not against democracy and republican principles of equality, but as the only way to put those principles into practice.

Historian CLR James was one of the first to elucidate the transformative power of violence from below as a defining feature of freedom in the Americas. His description in The Black Jacobins of the 1791 slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue, leading to the abolition of slavery and the rise of the first black republic, is eloquent: “The slaves destroyed tirelessly. Like the peasants in the Jacquerie or the Luddite wreckers, they were seeking their salvation in the most obvious way, the destruction of what they knew was the cause of their sufferings; and if they destroyed much it was because they had suffered much. They knew that as long as these plantations stood their lot would be to labour on them until they dropped… From their masters, they had known rape, torture, degradation, and, at the slightest provocation, death. They returned in kind.”

Haiti paid a hefty price for the slaves’ successful efforts at expanding the French revolutionary ideas of equality and freedom beyond its tepid limits. But it opened the modern world to an experiment in radical democracy in ways that became evident from the very first moment. Those who embraced this new, experimental freedom, saw Haiti as a symbol: When slaves in Richmond in 1800 revolted, they looked to the example of Saint-Domingue as they planned on marching into the city, kidnapping the governor, and killing the plantations’ owners (Gabriel’s Rebellion was quashed in its infancy). In 1805, slaves in Río de Janeiro still wore necklaces bearing the image of Dessalines, who the previous year had declared Saint-Domingue independence and founded Haiti, a unifying symbol of political struggle.

Those who feared the experiment acted accordingly. Jefferson lived in terror that the slaves of Virginia would learn from the example set by Saint-Domingue. In 1800, the Norfolk Editor published a note reminding readers that “the firing of sky rockets is both dangerous and improper: To those who have resided in St. Domingo it is well known that the negroes at the Cape kept their communications with the plantations by means of sky rockets—we therefore hope the practice will be discontinued.” The paranoia of the slaveowners was not misplaced. Even in the 1970s, the Black radicals that led the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit travelled to Cuba in 1964 to meet with Che Guevara and learn about revolutionary violence. Back at home, they undertook a collective reading of The Black Jacobins as “an example of how seemingly impossible rebellions could be successful.” Mario Santucho defined in these pages the challenges faced by revolutionary projects today by quoting the Italian philosopher Franco “Bifo” Berardi: “Victims can emancipate themselves from their role as victims only if they transform themselves into executioners.”

Violence—and the threat of it. “War to the death” was Bolivar’s call in 1813 and it led to the executions of Spanish prisoners that he wrongly thought would tame the royalists. The specter of extreme violence surrounded Pancho Villa during the Mexican Revolution. Frustration with the shortcomings and tragic ends of postwar democratic reform projects, combined with the ensuing reactionary backlashes, pushed Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, and later hundreds of thousands of Latin Americans toward revolutionary violence as the only way to achieve not a radical form of democracy but the only form of democracy possible. “Violence, real violence, is unavoidable,” Roberto Bolaño lamented at the beginning of one of his short stories, “at least for those of us who were born in Latin America during the fifties, and were about twenty years old at the time of Salvador Allende’s death.”

Of course, the recognition of revolutionary violence as a defining feature of Latin American democratic movements forces us to face the historical reality of revolution. During the twentieth century, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela were, in fundamental ways, the most powerful realizations of the Latin American rebuttal of American liberalism (and at the same time, an attempt to its full realization. For a generation like ours (and Grandin’s) that embraced Fidel, Ortega, and Chávez as representations of emancipatory politics, it is therefore not only a political but an intellectual obligation to explain how their regimes evolved into catastrophic failures for their populations, how the Josefina Vigil that hypnotized us in Moscow ended up prosecuted by Ortega, her relatives in jail, her words censured, how people from Venezuela and Cuba suffered poverty, political repression, and exile. How our dreams became their nightmares.

With regimes falling as you read this, it is worth asking how the book’s main arguments reflect on them. America América spends just a few lines in these failures. “Venezuela and Nicaragua are hard to defend, except historically, as the legacies of a long siege imposed by the most powerful country in human history,” Grandin says towards the end of this long journey through hope and carnage.

One thing is clear. Throughout the entire narrative, Grandin avoids like the plague any kind of moral equivalence that would equate “their” violence and “ours,” blurring an understanding of opposing visions and political actions, and their historical evolution. And rightly so. It would require a new book, even a new language, to convey how these revolutionary projects morphed into authoritarian regimes as a result, in part, of the triumph of the US’s emboldened confrontation against social unrest and collective emancipation. It is true, as Mateo Jarquín argues in his insightful book The Sandinista Revolution, that US policy makers “never enjoyed the level of control they would have liked” over Nicaragua. Indeed, the contras had their own local roots and their own demands against the Sandinistas. But as Jarquín also shows, it was their C.I.A.-backed muscle that made them powerful, “creating conditions that undermined FSLN popularity” and, more important, bolstering the more militarized and hierarchical aspects of the revolution. As with the other cases in the region, destroying ports, crippling economies, fueling paramilitary forces, invading sovereign countries, and sponsoring military coups hardly nourish the fresh stems of a democratic spring.

At the risks of simplification, the history that the region has lived, and the one Grandin tells, is more alive than ever. Published several months before Maduro’s abduction by US military forces, it would be impossible not to read the present crisis into Grandin’s brief description of President Cipriano Castro, Venezuelan president during the first eight years of the twentieth century. The strongman’s chaotic rule over the profitable tar production was overwhelmed by those much better and efficient than him in the arts of corruption and plundering: the American companies, policymakers, and journalists associated with the tar industry. In order to retain a large share of the country’s asphalt for a syndicated group in the US, they sowed chaos while mobilizing US battleships at sea and sympathetic judges on land. The Asphalt Trust funded from the US a revolt that led to thousands of deaths, testing every form of sabotage until a more compliant administration conceded to their demands.

Maybe the real magpie of the US empire is not so much Latin America itself but Grandin’s formidable theoretical apparatus, gathering an almost infinite array of events and plunging them back into the streams of history to make them intelligible. America América can also be read as the culmination point of the author’s intellectual project of several decades, driven by outrage at the role the US empire played in the atrocities of the region’s colonial and modern history and, equally important, at the ways in which the US refines its domestic barbarisms in the hemispheric arena. From his first book, The Blood of Guatemala, to The End of the Myth, Grandin has mapped out the hemispheric interactions that are the heart of America América, but he is increasingly irked by the ways in which US liberalism betrayed its promises, ravaged a region, and prepared the country for the arrival of today’s nihilistic fascism. His is not “national history” in the limited, old-fashioned meaning of the expression, but a history of the nation (the most powerful nation in history) dialectically built upon its neurotic tensions with the outside world, always offering limitless expansion and existential threats.

But if we venture into the history of the Americas not through the US fortified gates but through its southern entrance, Latin America might offer, unlike Grandin’s suggestion, a non-immanent critique to Anglo-Saxon liberalism: Revolutions showed that only violence from below, and not liberal democracy from above, has pushed the restrictive borders imposed by recalcitrant elites over the redistribution of wealth and the expansion of people’s rights, offering a form of truly contested democratic power. America América is a powerful engine to think about those revolutions. The book might not be a machine that kills fascists, at least not literally. But it’s an indispensable one to defeat them.

Ernesto Semán teaches Latin American history at University of Bergen, in Norway. His latest book is Acá falta alguien, a novel.