Issue 42 of The Ideas Letter begins with a meditation on two recent books of consequence: Peter Beinart’s Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza and Pankaj Mishra’s The World After Gaza. Linda Kinstler, an uncommonly subtle and discerning writer, takes the measure of the texts and asks whether the catastrophes of the present can inspire learnings for the future.

Our spotlight then stays on Beinart as the writer Eric Alterman reflects on the reception of Beinart’s book and the complicated personal and intellectual journey Beinart has taken over the decades.

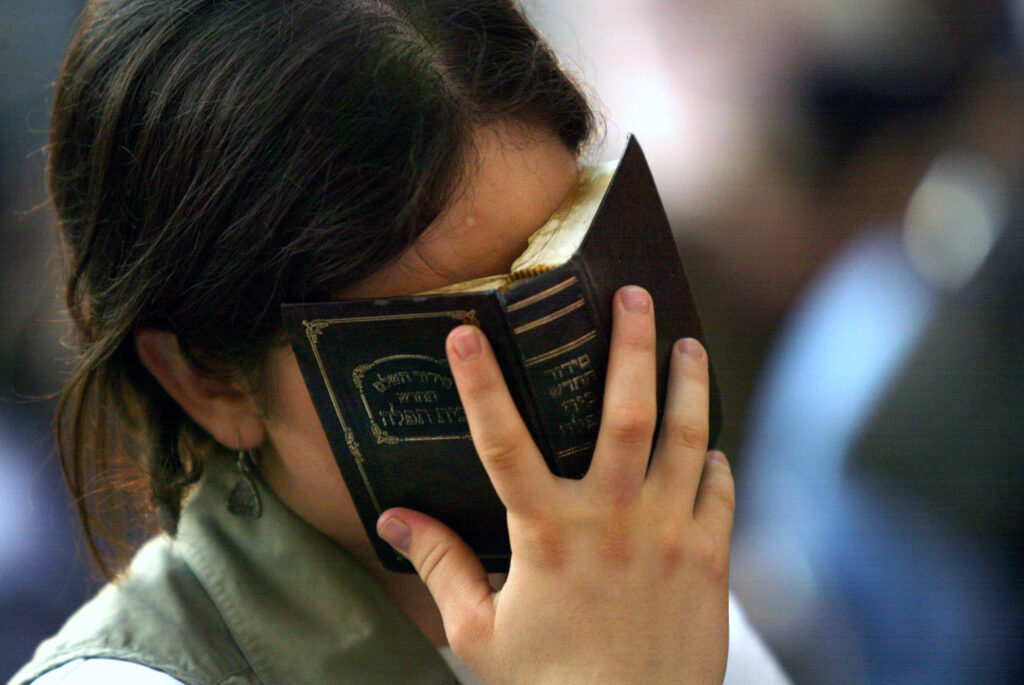

A searching essay from the writer and editor Celeste Marcus sustains this issue’s meditative register, as she imagines her own tradition of Judaism as a palimpsest, and all that this implies for the structuring of her faith.

Our curated section leads with an inspired interpretation of the Argentine made-for-TV science fiction series The Eternaut by Jordana Timerman, managing editor of The Ideas Letter. She writes about how ordinary people face existential dread, and how the adaptation of the classic reflects a society scarred by decades of dictatorship and economic crises.

Argentina stays in focus with scholar-activist Verónica Gago, who takes stock of the last decade of feminist organizing in the country and its turn for the worse under President Javier Milei.

We follow with a taped discussion with the writer John Cassidy on his masterful new doorstopper Capitalism and Its Critics: A History from the Industrial Revolution to AI. Cassidy covers essential ground in this conversation with the economist-pundit Doug Henwood.

We conclude with an interview with the historian Sandipto Dasgupta about his own new book Legalizing the Revolution: India and the Constitution of the Postcolony which focuses attention on the complicated road from anticolonialism organizing to the creation of a constitutional order.

Our musical selection could be from only one person: Sly Stone. Stone, who died this week at his home in California, fused funk, soul and rock to create a music like no other. He was a monumental figure in popular music and a harbinger of the unforgettable funk revolution. Here is the anthemic “Stand” from his 1969 eponymous record.

—Leonard Benardo, senior vice president at the Open Society Foundations

A Measure of Things Human

Linda Kinstler

The Ideas Letter

Essay

In Kinstler’s reading, recent books by Pankaj Mishra and Peter Beinart grapple with the moral and historical implications of Israel’s war in Gaza by arguing that it marks a rupture comparable to past foundational traumas like the Holocaust or apartheid. Both authors challenge the continued use of Holocaust memory to justify Israeli violence, urging a redefinition of Jewish identity and global moral narratives in which victimhood can no longer excuse domination. Yet Kinstler questions whether this moment truly heralds a new era or merely adds another layer to the ongoing devastation.

“In their conviction that the world after Gaza will be fundamentally different than the one we have previously known, these authors convey a dim hope. Mishra asks whether we may yet free ourselves from the ‘Manichaean historical narratives’ that have for so long entrapped us and abandon ‘strange quests for guiltlessness’—although, phrasing these as merely questions for consideration, he seems slightly unconvinced that we can or will. Beinart underscores his belief that change will come for Palestinians just as it did for Black South Africans. … One very much wants to believe that they are right, that one day we will look back upon the present and see it clearly as a time of incontrovertible epochal change, a moment when the mass slaughter of innocents was answered by serious legal and political shifts.”

As Witness and Prophet

Eric Alterman

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Beinart, a prominent Jewish critic of Israel’s policies, argues that the moral identity of American Jewry must reckon with Israel’s actions, which he views as genocidal and incompatible with Jewish ethical teachings. Though Beinart’s call for a binational democratic state is widely viewed as politically implausible, it still receives astonishingly histrionic responses. Yet the book’s respectful treatment in the mainstream press evinces a marked shift in U.S. public discourse regarding Israel over the past two decades, according to Alterman.

“In many ways, the reaction to Beinart’s recent book … demonstrates important truths in his argument: He relies on his religious training and beliefs to show that many American Jews’ ‘idolatry’ of the state of Israel is actually contradicted by many teachings in both the Torah and the Talmud, and by the rabbis who, for centuries, have interpreted those texts. In one of the more sensitive discussions of the book, the much-admired Jewish historian David N. Myers … accurately described it in The Markaz Review as a cri du coeur and ‘an expression of Beinart’s deep pain and exasperation that Jews have failed to acknowledge the monumental devastation and suffering that Israel has wrought in Gaza—which he has publicly described as a genocide.’”

Confronting Words

Celeste Marcus

The Ideas Letter

Essay

In this deeply personal essay, Marcus plumbs the contradictions and paradoxes of her Jewish faith. God, as she writes, seems to change color and shape from one prayer to the next. What do the ancient tensions that constitute Jewish tradition mean in the 21st century? She finds her faith is best thought of as a palimpsest, marked by the needs and hopes of past generations – and the generations that have yet to come.

“One way of describing the porousness of Jewish faith and the elasticity of Jewish practice is toleration. The tradition is tolerant of many different iterations of itself. This toleration was a mechanism of self defense: it is what facilitated the perpetuation of the religion. But for a young person keen to find a formula for expressing religious fervor, this laxity was maddeningly unhelpful. I was scrutinizing the text with such zeal, trying vainly to discern within it a framework for relating to the infinite. I recognize now that the appetite I was trying to sate was not philosophical at all but spiritual. I wanted God. And God was everywhere and nowhere. In our texts, in our rituals, God is constantly invoked but never concrete – every time He comes into view, every time one text expresses a theology, some other, equally authoritative document or practice offers a competing vision. What is the Jewish God? How can we love Him?”

The Eternaut Speaks To Our Uneasy Times

Jordana Timerman

The Guardian

Essay

Aliens almost always destroy New York, but in Netflix’s The Eternaut the invasion comes to Buenos Aires – a powerful geographic shift to the global south that frames a different take on the usual science fiction tropes. The story, based on a 1950’s cult classic comic, isn’t about a lone cowboy who saves the day – it’s about how ordinary Argentines face existential threats together. There is no single savior in the story, according to the comic’s author, Héctor Germán Oesterheld, who celebrates the “collective hero.”

“In the series, that appreciative perspective has shifted to Argentina’s besieged middle class, once the pillar of the country’s exceptionalism, now eroded by inflation and austerity. This too is tacitly political. In Milei’s Argentina, where public universities are defunded, cultural institutions gutted and social programmes under attack, the show’s message of collective survival, of interclass solidarity, is its own quiet rebellion. Though filmed before Milei’s election, its ethos cuts against the libertarian gospel of radical individualism. Even the tagline – Nobody is saved alone – feels like resistance. The symbolism has been adopted by scientists protesting against austerity budget cuts who recently demonstrated against ‘scienticide’ wearing Eternaut-style gas masks.”

The Reinvention of the Strike

10 Years of Feminist Uprising in Argentina

Verónica Gago

NACLA

Essay

Ten years after the women’s rights movement Ni Una Menos took Latin America by storm, Gago, a founding member, reflects on how feminists in Argentina have reshaped the meaning and function of the strike, transforming it into a tool of mass political pedagogy, transnational solidarity, and collective reorganization around social reproduction. This decade-long cycle of transfeminist mobilizations confronted neoliberal and patriarchal violence through expanded demands around care work, debt, housing, and bodily autonomy—only to face an intense counterrevolutionary backlash culminating in the rise of far-right governments like Javier Milei’s, which institutionalize anti-feminism as a pillar of authoritarian neoliberalism.

“It is no longer enough to speak of a ‘crisis of social reproduction’ in order to explain the dynamics of neoliberal capitalism. We’ve witnessed a veritable war against social reproduction, of which the pandemic and the victories of the far right are both cause and symptom. These forms of war are exacerbated to produce what we might call, following Silvia Federici, the ‘fascistization of social reproduction.’ … In Argentina, the crisis-war-fascistization sequence can be read as a counterrevolutionary response to forms of politicization of social reproduction that emerged in response to the crisis of legitimacy of neoliberalism in the early 2000s, as well as with the massive growth of the transfeminist movement.”

Capitalism and Its Critics

John Cassidy

Center for Brooklyn History

Video

New Yorker writer John Cassidy discusses his new book, which traces 200 years of capitalism through the perspectives of its critics—from Adam Smith to Marx, feminist thinkers, and contemporary voices—highlighting the economic order’s constant cycles of crisis, adaptation, and resistance. While capitalism has shown remarkable resilience and innovation, it is now facing a convergence of existential threats—AI-driven labor disruption, climate change, rising inequality, and authoritarian populism—that expose the system’s deep contradictions and unsustainable trajectories.

“I don’t think it’s that the system thrives on crisis, it’s that its inner contradictions, to get Marx in about it, lead to crisis. The system is built on innovation and the profit motive and that combination of factors has proven incredibly durable and sort of innovative. I mean you have to recognize the sort of creative power of capitalism, which Marx did… So the early critics of capitalism recognized its incredible sort of productiveness, how could you not, but allied to that are sort of you know tendencies to destruct that obviously on the long term generates class conflict, generates financial crisis. Now we find it’s always generated pollution and externalities and … Bad noxious outpourings of all types that they seem manageable for a long time. Now it turns out they may be burning the planet. So that in itself is an existential threat of capitalism. So I don’t know if it thrives on crisis, but it’s certainly integral to the system.”

From Anticolonialism to Constitutional Capture

An Interview with Sandipto Dasgupta

Zainab Firdausi

Journal of the History of Ideas Blog

Interview

India’s postcolonial constitution was shaped less by popular revolutionary ideals and more by the inherited apparatus and logic of the colonial state, privileging administrative over democratic modes of governance, argues Dasgupta. He contends that concepts like democracy, property, and constitutionalism were reconfigured through anticolonial struggle, but ultimately constrained by technocratic and elite decision-making that sidelined mass political participation.

“To be successful, anticolonial movements had to become popular movements—that is, they had to mobilize the masses. Yet, as I mentioned earlier, the very success of that mobilization generated anxiety among the elites. As a result, there was a deliberate distancing of the postcolonial institutions from the popular political expressions of the anticolonial cause. This separation of the popular from institutional politics was, to my mind, a separation of the anticolonial and the postcolonial, and it shaped postcolonial political life.”