The historian Greg Grandin has had an illustrious career smashing the shibboleths of Latin American history, especially as they relate to El Norte. His recent book, America, América, a five-century history of the Western Hemisphere, argues that a US national identity was forged not only in relation to Europe but “facing south,” in interaction and conflict with Latin America. The Argentine social and environmental historian Ernesto Semán—also a full-fledged ”salmonist” these days (you’ll need to ask him)—offers a critical appraisal and personal reckoning of Grandin’s take on the intertwined histories of imperialism and resistance.

Next, the Cambridge University sinologist Christian Sorace offers a critique of the now-common tendency within the punditocracy to analogize Donald Trump to Mao Zedong—and Trumpism to Maoism. Sorace explains that such historical analogies, though rhetorically appealing, obscure more than they clarify. They flatten political nuances, misrepresent mass politics, and reinforce liberal complacency rather than encourage new forms of democratic thought and action.

There has been a common thread to the work in exile of Anna Narinskaya, a displaced Russophone journalist who spent years at the publications Kommersant and Novaya Gazeta, bearing witness to the Kremlin’s normalization of cruelty. This essay—an account of the transformation of defendants’ “last words” in Russian political trials into a new form of underground literature—interweaves documentation, history, and reflection to reveal how the courtroom, a space of state repression, paradoxically became the last refuge of truth-telling.

Our curated section kicks off with the literary critic Terry Eagleton, better known as the father of our frequently featured writer/editor Oliver Eagleton, who pens a very funny and appropriately sour text on Schopenhauer in the LRB.

We follow with a critical meditation in the Hedgehog Review by Antón Barba-Kay on the “meaning” of Curtis Yarvin—his ideas, influence, and style of politics—framed around his debate last year with the Harvard political philosopher Danielle Allen. What exactly is this thing some call the Dark Enlightenment?

Our musical selection is a new composition from the nonpareil guitarist Marc Ribot, a song of mourning and loss, “Elizabeth,” which brings to mind the most personal songs of Lou Reed in his own tragic record Magic and Loss.

—Leonard Benardo, senior vice president at the Open Society Foundations

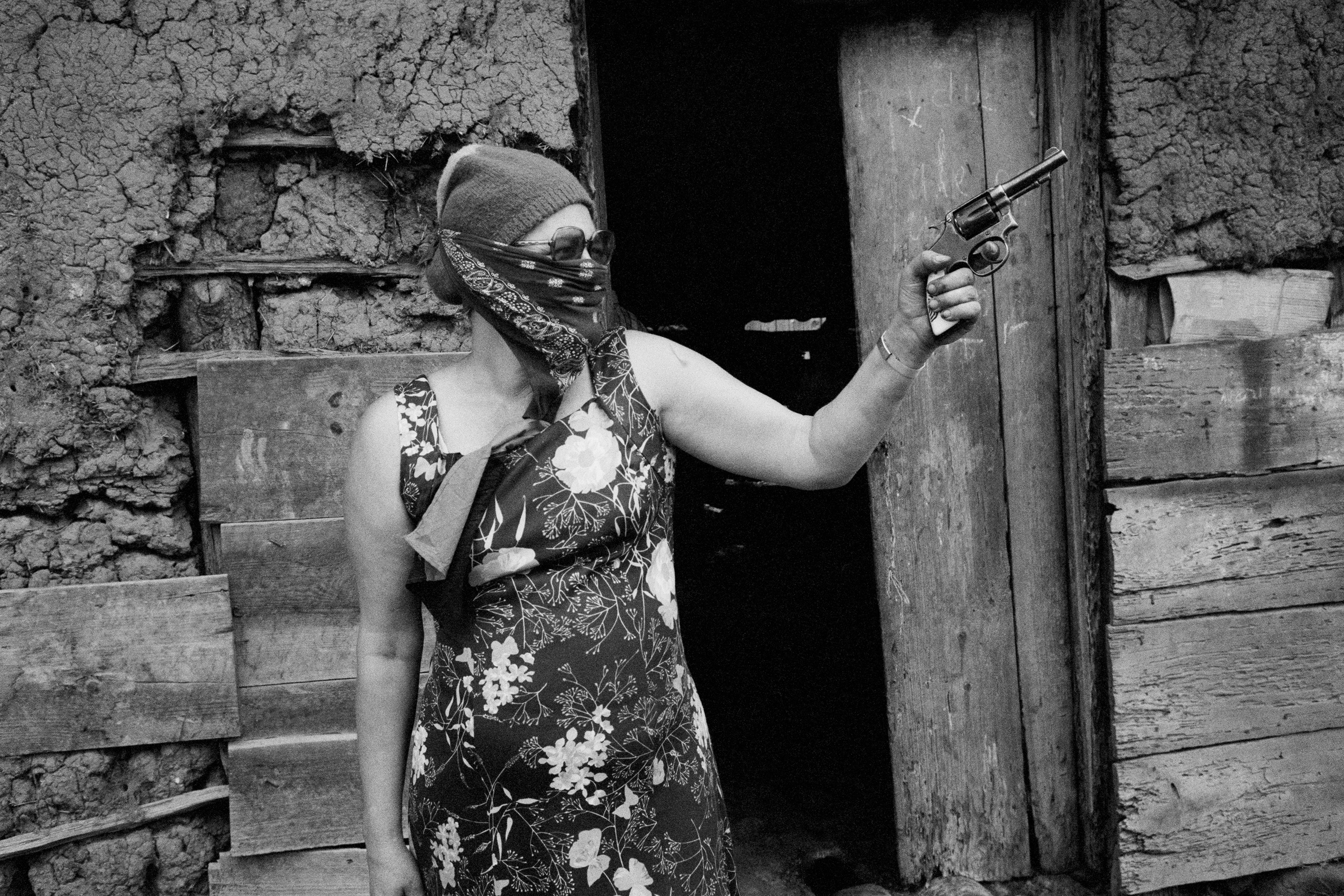

Thirty Yards from Revolution

Ernesto Semán

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Semán reads Greg Grandin’s America América as a monumental rethinking of hemispheric history, arguing that Latin America has long functioned as the United States’ immanent critic—exposing, generation after generation, the gap between US ideals and US power. He shows how Grandin reconstructs the Americas as a single, entangled political space, in which Latin America’s experiments with radical democracy repeatedly challenged and reshaped liberalism in the US, even as they were violently quashed by the hegemon itself. The essay presents America América not only as an engaging account of the intertwined history of empire and resistance, but also as a powerful intellectual tool for understanding the limits of liberal democracy and the conditions under which more egalitarian political orders have emerged.

”The establishment of liberal electoral systems and the embrace of moderate political projects that grounded the democratic transitions in the region was not overdetermined but the result of the remarkable effort of individuals and societies historically situated. I’ve always marveled at why, after years of state terrorism and when most of those accused of human rights violations roamed free, people didn’t just go and put a bullet in the head of those who had raped, tortured, and killed our loved ones. But they didn’t. Instead, people joined human rights organizations. They became members of political parties and exerted pressure over parliaments. They ran for office. They rallied in the streets. They sued criminals in lengthy processes through archaic judicial systems, many times still influenced by the very perpetrators of state terrorism. They litigated in international tribunals and learned about similar cases in other parts of the world. They opted out of violence and collectively bet on the boring and frustrating way forward. And in doing so, they helped to build robust civic principles and a more humane world.”

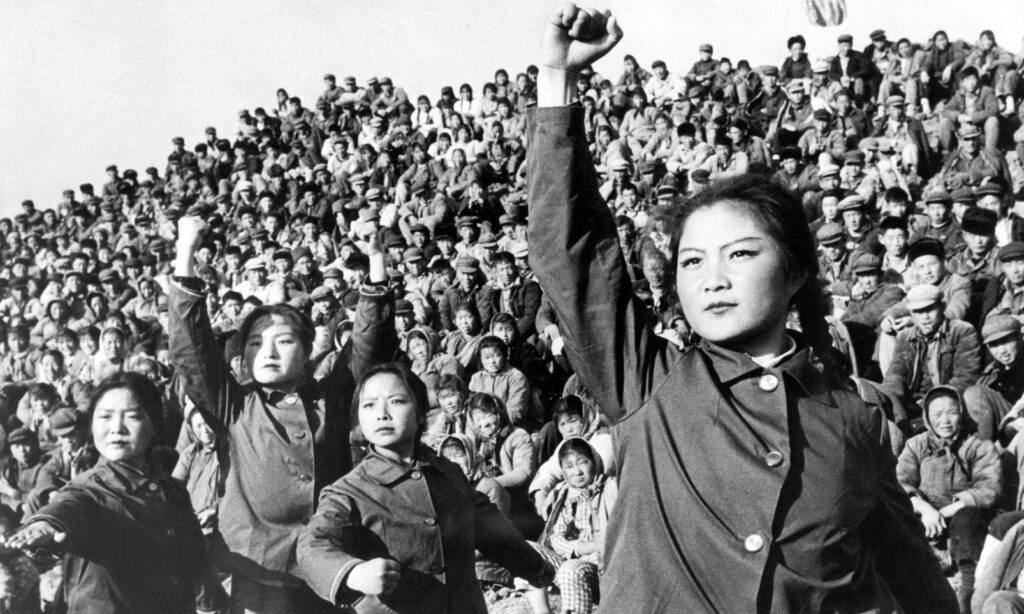

Where a Hundred Analogies Bloom

The Perils of Comparing Trump to Mao

Christian Sorace

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Routine analogies between Donald Trump and Mao Zedong are not only historically inaccurate but intellectually disabling, contends Sorace, because they replace structural analysis with a moral fable that collapses distinct political projects into a shared vocabulary of chaos and demagoguery. Turning to history for analogy rather than inquiry normalizes the limits of liberal politics, obscures the specific social conditions that gave rise to Trumpism, and elides the pressing need to “reinvent democracy and find an exit from capitalism.”

“What is the purpose of an analogy so brittle it crumbles under the slightest historical weight? When it comes to Mao/Trump, accuracy was never the point: Many of the parallels casually slip out of the worn-out suit of Maoism into the shapeless garb of Chinese authoritarianism thrown over a mannequin of Oriental despotism.”

The Last Word in Russia’s Courts

Anna Narinskaya

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Narinskaya traces how Russia’s long-standing tradition of allowing defendants in criminal trials to say a “last word” has evolved under Vladimir Putin, from a vestige of legal decorum into—at least until recently—one of the regime’s last spaces of truth-telling. These courtroom statements, some circulated illicitly, resonate as literature, journalism, and political testimony all at once, she argues. And then the state clamped down.

“Some time ago a website called Final Statement was created to publish these courtroom closing pronouncements. Read these texts back- to- back and their shared essence becomes clear, united by a special pathos—extreme sincerity, even desperation. The tone of some recalls a religious sermon or a public political speech. Together, they are a literature of direct expression and make up a distinct genre. … Precisely because verdicts in political cases in Russia today are predetermined, the defendants’ last words are disconnected from real consequences, and they can function as art and operate by art’s rules. Their purpose is not to change a verdict; it is to change an atmosphere in society by saturating it with molecules of truth. That’s how poetry works.”

Pregnant with Monsters

Terry Eagleton

London Review of Books

Essay

Eagleton uses David Bather Woods’s biography of Schopenhauer as a springboard, borrowing his life-and-works format to revisit the philosopher’s central idea of the blind, impersonal Will. Eagleton argues that this doctrine offers a grim but prophetic account of modern subjectivity—one that undermines autonomy and progress.

“Woods doesn’t delve deeply into The World as Will and Representation, without which Schopenhauer’s name would almost certainly have faded from the historical record. Whatever one thinks of its perpetual grousing and homespun moralising, there is a science-fiction-like horror at the heart of the book which was to become an important feature of modern thought. At the core of the self is something—the Will—which is implacably other to that self, an inert, intolerable weight of meaninglessness, as though we were all permanently pregnant with monsters. What makes me what I am is utterly indifferent to my individual identity, which it uses simply for its own pointless self-reproduction. This Will, which is the pith of my being, is yet absolutely unlike me, as blank and anonymous as the forces that stir the waves. What is now irreparably flawed is subjectivity itself, not just some perversion or estrangement of it. It is what we can least call our own. We are leaving behind the Kantian era of the autonomous, self-fashioning individual, the free agent of its own destiny, for a world in which we are the playthings of impenetrable powers.”

High Priest of the Dark Enlightenment

The Techno-Futurism Is Now

Antón Barba-Kay

The Hedgehog Review

Essay

According to Barba-Kay, Curtis Yarvin is less a serious political philosopher than a skilled provocateur with a Dark Enlightenment style that exposes real weaknesses in contemporary liberalism—especially its stagnation, its reliance on unexamined assumptions about democracy, and its claim to moral and epistemic neutrality. While Yarvin’s questions about first principles resonate because liberal democracy has grown bad at defending itself, his answers reduce the state to a technocratic “customer service” provider; he offers disruption and irony in place of a defensible moral vision or workable alternative.

“The greatest theoretical strength of NRx writers is their willingness to conjugate new political forms with the first principles of digital practice. Like Thomas Hobbes, they purport to look at politics from an engineering perspective. Politics needs ‘rebooting’; violence is something to be programmed out. Both Yarvin and Srinivasan … envision a world in which people are governed in smaller statelets, each of which could be joined or exited at will, and each of which would be governed by its own legitimate dictatorships and laws. Just how this ‘Patchwork’ of statelets might come about or why they should not be swallowed up by larger Leviathans is not clear. Nor is it always clear that such statelets need to be fleshed out into analog reality. In Srinivasan’s account, we should be thinking of a new form of sovereignty—based on blockchain technology—that would not necessarily require territorial control at all. And even if this does not look viable enough to become political reality, Yarvin and Srinivasan have put their finger on a problem that autocracies the world over are sedulously working to rectify through their national management of social media and cryptocurrencies. The United States needs a response in kind, if it hopes to avoid a permanent war of dysfunction between our two digital states, our two pills to wonderlands blue and red.”