Bernard E. Harcourt and Dylan Riley are two of today’s foremost social theorists, Harcourt at Columbia and Riley at Berkeley. We are privileged, in our Issue 39, to feature their essays, which respectively endeavor to develop a new framework and a new conceptual vocabulary to apprehend our dismal moment.

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins is a rising star in the world of intellectual history. In our interview, I was eager to get purchase on how the ongoing renaissance in intellectual history has influenced public debate, and whether this has benefited the reading public outside of the academy.

In our curated section, we lead with an interview with the incomparable Albie Sachs, the South African freedom fighter and former Constitutional Court judge. His biography establishes him as an archetype of moral courage. We then continue with another South African story, this one a dissection into the oft-forgotten radical wing of the long struggle (one wonders what Sachs would have said about the historical revisionism). Finally, we feature a riveting podcast on the esteemed British psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott, which covers considerable territory about many of your favorite analysts… and analysands!

Our musical selection for Ideas Letter 39 is from the tenor genius Albert Ayler and his stentorian, rip-roaringly aggressive, and beautiful version of the Gershwin classic “Summertime.” It’s from 1963 and was recorded in Copenhagen, a city that like Paris many American jazz musicians gravitated to fleeing racism and seeking cultural acceptance.

—Leonard Benardo, senior vice president at the Open Society Foundations

A Modern Counterrevolution

Bernard E. Harcourt

The Ideas Letter

Essay

The Trump II administration’s onslaught of executive orders and emergency declarations, and its effort to expand presidential power, is both extraordinary and in the lineage of U.S. governments past, Harcourt argues. It is less about the doings of one man than about much vaster forces at play worldwide. Its playbook is a more relentless expression of counterinsurgency warfare logic and strategies first developed at war, which for decades now, have been brought back and applied within the U.S. In this initial period, Trump II has deployed three main strategies: creating internal enemies, eliminating those internal enemies, and winning the hearts and minds of the American people.

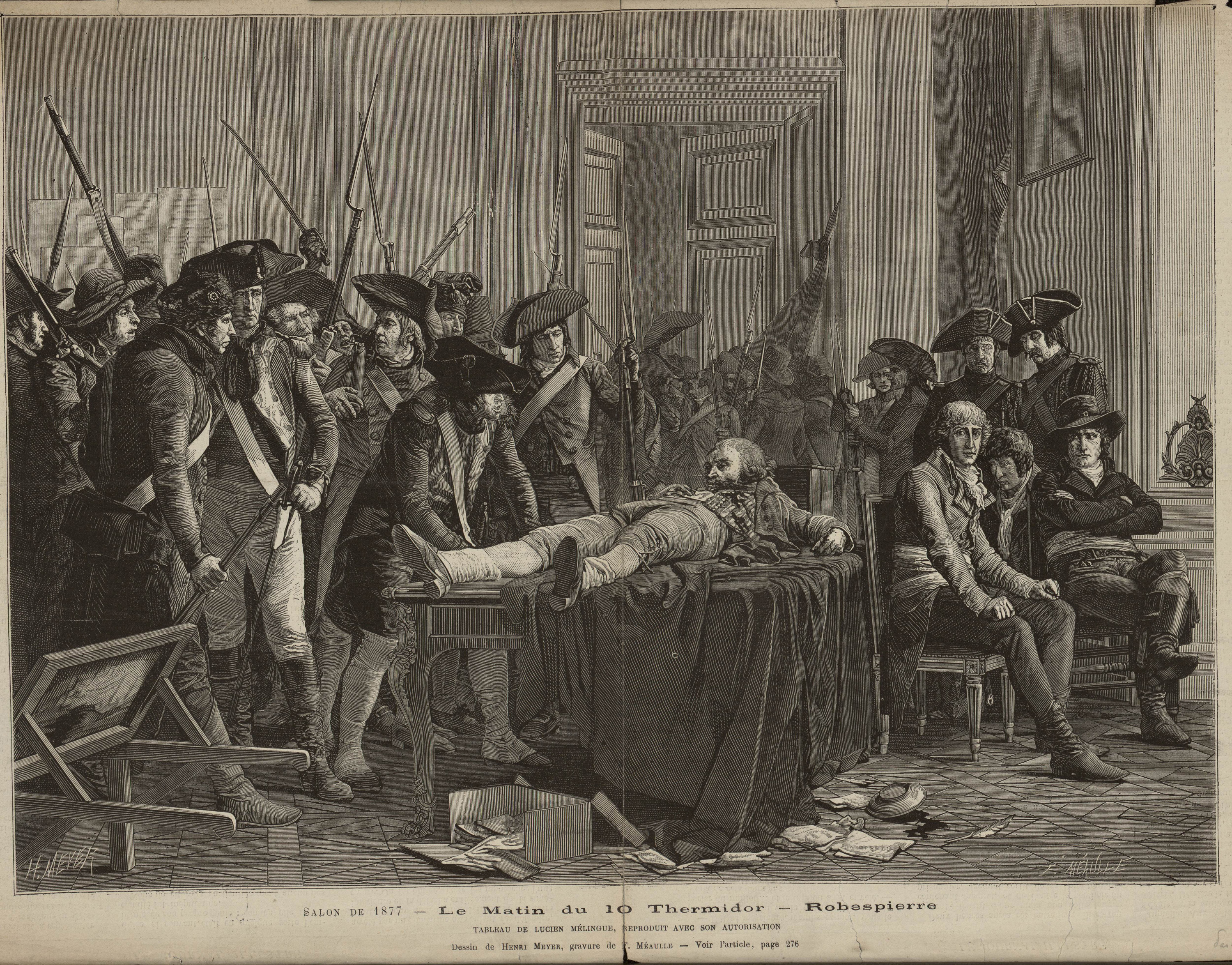

“In fact, the Trump II administration represents the demolition phase of a new offensive in a decades-long counterrevolution. … In effect, President Trump’s actions during the first hundred days of his second mandate are the latest episode in a vast and coherent modern counterrevolution with a longer historical arc and a broader global reach. … Consider Marx’s argument in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. The rise of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte in 1848, Marx claimed, was not simply a ‘great man’ story; instead, it demonstrated ‘how the class struggle in France created circumstances and relationships that made it possible for a grotesque mediocrity to play a hero’s part.’ The sentence’s humor should not obscure its theoretical thrust. Likewise, our diagnosis of President Trump today must focus on the broader social conflicts and economic forces that are propelling history at a global level, not on the rise of any one individual—even if he resembles a grotesque mediocrity.”

Reflections on an Inverted Revolution

Dylan Riley

The Ideas Letter

Essay

The U.S. extreme right has torn a page from Leninism and is carrying out a Bolshevik-style revolution with inverted values. The class state that Lenin and Gramsci believed must be smashed is, for the second Trump presidency, the administrative state that represents the interests of the “Left.” Riley argues that Trump II “must be understood sociologically as a conflict between a revolutionary movement that has seized the state and a still-strong Old Regime that is under severe attack.” But Riley emphasizes a difference that could point to a path of ideological resistance: MAGA’s intrinsic nihilism.

“What sort of ideological appeal can MAGA make: personal enrichment, smashing, plunder? Is the idea that the ‘base’ will participate vicariously in the orgy of self-dealing? Perhaps it offers the pleasure of vengeance or simply the joy of witnessing cruelty raining down on the weak and defenseless. But this is not a worldview: Nihilism, not ideology, is the glue. This is most evident from the rationalizations for the new tariff regime. In a vague echo of the various justifications of revolutionary violence offered by the Leninist tradition, we are told that they are the price that must be paid to reach the El Dorado of American Greatness. But no one can figure out even in theory how this is supposed to work. In understanding these policies, knowledge is a positive handicap for it leads the analyst to impute a rationality where none exists. The phenomenon of “sane-washing” is the latest iteration of Hegel’s Owl of Minerva: the attempt to impute a rationality to historical actions which escape the explicit intentions of their authors.”

Intellectual Historians Confront the Present

An Interview with Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

Leonard Benardo

The Ideas Letter

Interview

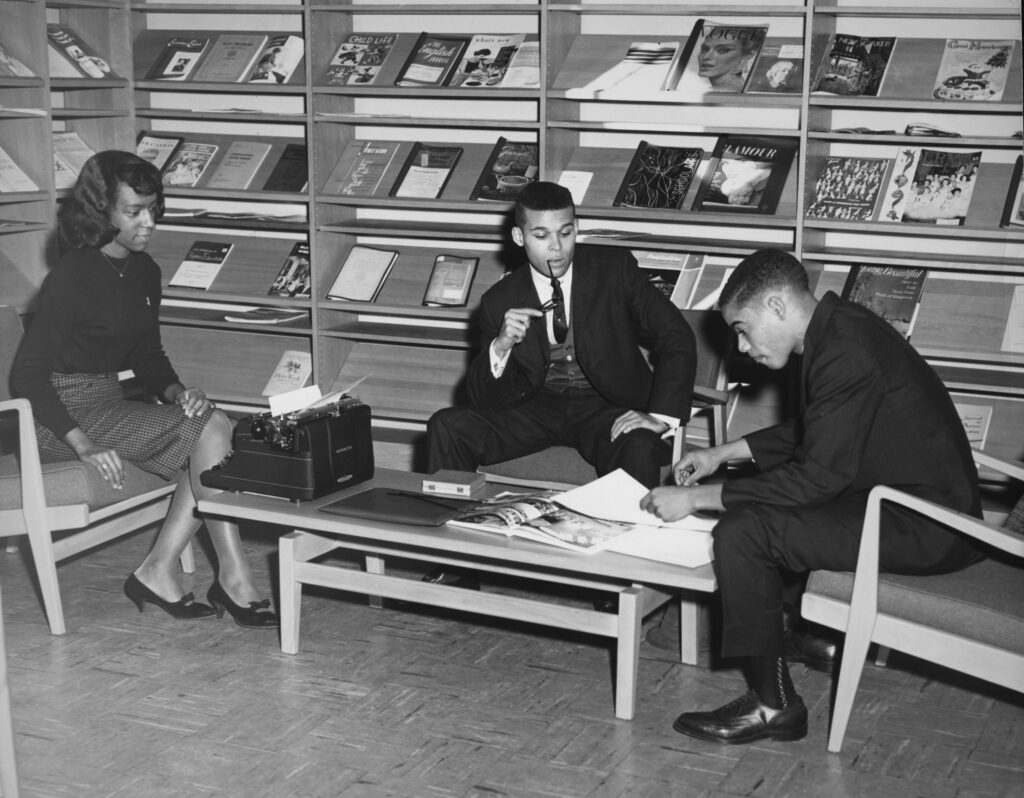

Intellectual history is having an unanticipated resurgence—and that resurgence is taking place largely outside academia. A newer generation of historians is responding to job precarity by publishing in magazines, podcasts, and Substacks. They are applying their skills to address the crises of our time for a general audience desperate for answers, according to Steinmetz-Jenkins. But he is concerned that these so-called “resistance historians” are not only preaching to the choir but also failing to articulate productive responses to the extreme right.

“I am an advocate of using history to understand the present—I teach a class on it, have written about it, etc.—primarily because looking to the past is simply an unavoidable existential need that humans have when trying to make sense of their times. However, I have grown in my concerns about presentism, and especially because of the overly political way it has been used to resist Trump, which has led to some rather poor history, in my opinion. When making historical analogies it is essential that they be accompanied by disanalogies since no era is exactly the same. As Samuel Moyn puts it, ‘The past is not simply a mirror for our own self-regard.’ Of course, the present is, in a sense, a product of the past. Holding these together in tension can do much to avoid crude forms of presentism.”

What Comes After Liberation?

An Interview with Albie Sachs

Riason Naidoo

Africa Is a Country

Interview

In this broad-ranging interview, the freedom fighter and former Constitutional Court justice Albie Sachs, now 90, reflects on law, liberation, and the unfinished work of building a just South Africa. The topics he covers range from his survival strategies in solitary confinement to his deep valorization of culture.

“I’m in New York, and I’m invited to speak at the House of Culture in Stockholm. Eventually I’ve flown all across the Atlantic, and finally I’m only given five minutes to speak. Speakers before me were all saying the same thing, ‘Art is a weapon of the struggle.’ So, I thought, I’ve got five minutes; I am going to make two points. The first thing I say is, ’We don’t want your solidarity criticism. We want real criticism.’ There is stunned silence. Even though I don’t believe in censorship, I said, ‘I believe we should ban the statement “Art is a Weapon of the Struggle” for five years.’ Conservatives thought, Albie has seen the light at last. What I meant is that art is much more profound. We need to see the good in the bad, the bad in the good. As revolutionaries do we never make love? At night when you go to bed do you discuss the role of the white working class?”

South Africa’s Radicals

The Anti-Apartheid Movement’s Forgotten Wing

Marcel Paret and Zachary Levenson

Souls

Journal Article

Contrary to the dominant narrative portraying South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement as an ANC monolith, Paret and Levenson seek to rescue the movement’s radical tradition, which insisted that the struggles for socialism and a racially inclusive democracy were intertwined and should not be understood as successive stages of a political trajectory. And they still are that, as well as a framing relevant for activists fighting racial capitalism today, both in South Africa and around the globe.

“Developing their strategic critiques within the ‘context of struggle,’ the movement’s radical wing dismissed the two-stage approach as insufficient, toothless, and above all, ineffective in actually confronting the racist inequalities unleashed by centuries of apartheid and colonial rule. As an alternative, South Africa’s radicals offered approaches that prioritized a Black working-class struggle against both apartheid and capitalism simultaneously—or what some members of this wing termed ‘racial capitalism.’ Indeed, in some circles, the idea of racial capitalism symbolized precisely the interconnectedness of racial and class domination, and the necessary linkage of the struggles against them.”

D. W. Winnicott

Dialogue with Abby Kluchin and Patrick Blanchfield

Sam Kelly

Red Medicine

Podcast

The hosts of the podcast Ordinary Unhappiness, Kluchin and Blanchfield, discuss the legacy of Donald Wood Winnicott, one of Britain’s most influential psychoanalysts, including his work about the construction and the destruction of the welfare state and how it can contribute to an analysis of care. One of Winnicott’s best-known theories is that of the “good enough” mother, in contrast to the impossible standard of the “perfect” mother, and he delves into the hatred some mothers feel toward their babies, in addition to love.

Blanchfield says: “But this notion of, not only the necessity, but the sort of generativity of hate, I think was interesting for us to explore, especially at a time when it feels like hate is the thing that has us deadlocked rather than is the thing that can provide some sort of impetus for change, right? And in that way, what if we thought about hate not necessarily as maladaptive, but actually as adaptive in terms of not only individual, but also political dynamic change?”