In their visions of the future, socialists must begin accounting for artificial intelligence. So far, according to Evgeny Morozov, they’ve relied on old chestnuts rather than developing a strong theoretical basis for an AI-inflected socialism. Morozov argues that socialists should embrace the messy, “impure” nature of technology in order to shape a more humane future. This may just be the launching of a new theoretical program.

Regarding research programs, the historical sociologist Dylan Riley doesn’t consider Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism to be a useful intellectual guide to understanding today’s global malaise. Might Antonio Gramsci offer greater purchase on the state of play? Riley’s ultimate answer is to look squarely at politics, and to understand the damaged connections between the public and private spheres.

Matthew Shipp is perhaps the world’s premier avant garde jazz pianist whose personal language fuses innumerable influences yet remains unmistakably his own. In my interview with him, Shipp takes up questions of creative influence and personal sound, reflecting on the limits of language, the ineffable nature of originality, and how true greatness requires deep unlearning.

Our curated section kicks off with a lacerating review from Oliver Eagleton of Shadi Hamid’s grasping defense of American power in The Baffler. Stand guard all of you who purport to defend democracy à l’américaine!

We follow with Ida Danewid’s reinterpretation of the politics of James Baldwin, from a liberal champion of rights and equality to a more radical participant in global struggles. Does she succeed in her efforts to “undomesticate” Baldwin?

Last, my longstanding comrade-colleague, Darius Cuplinskas, interviews the naturalist Robert MacFarlane for the New Books Network. MacFarlane’s wildly popular new title, Is a River Alive?, asks trenchant questions about the lived realities of these natural flowing bodies of fresh water.

Our musical selection to close the year is from the Hungarian maestro György Ligeti. The stakes are high with Matt Shipp following along, but “Lontano,” a floating dreamscape of timbre and harmony, meets the moment. Ligeti was a fan of what he dubbed “micropolyphony,” with independent musical lines at different speeds forming clusters rather than counterpoint. The composition may be a fitting end to a complicated year.

We are taking a short break for the Northern Hemisphere’s winter holidays but will be back for Issue 55 on 8 January. Stay well!

—Leonard Benardo, senior vice president at the Open Society Foundations

Socialism After AI

Evgeny Morozov

The Ideas Letter

Essay

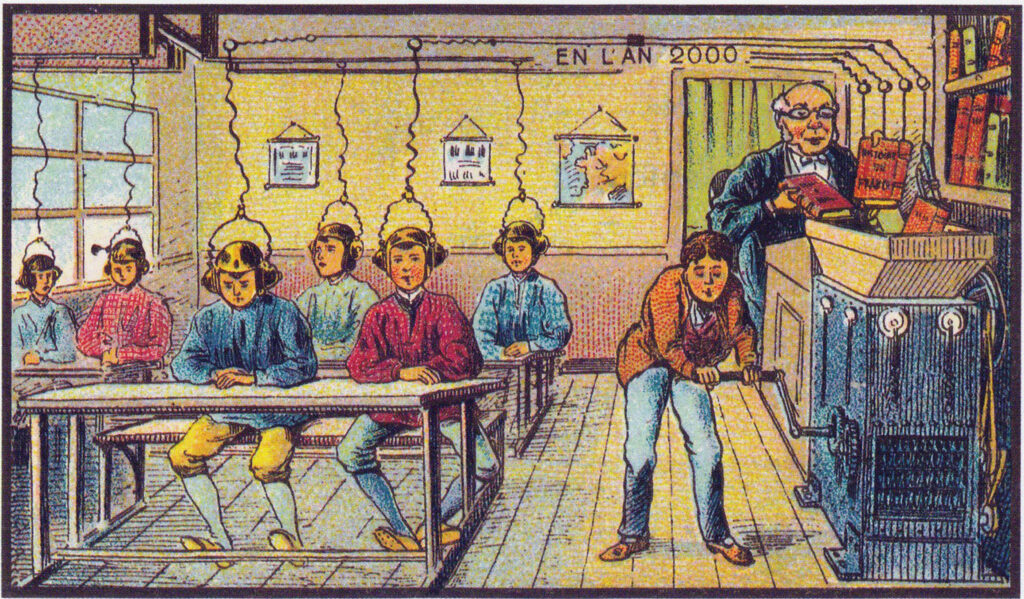

Morozov argues that socialist attempts to harness AI have merely treated it like earlier tools of capitalist production—as a neutral instrument that can simply be redirected. In fact, he says, it is a force that actively shapes social values and human capacities. Using as a foil the model Aaron Benanav devised based on multiple criteria to promote democratic engagement, he shows how even sophisticated socialist blueprints still rest on a mistaken view that separates politics and technology, forged when the paradigm of progress was the conveyor belt. That’s not good enough, especially not when it comes to AI, in Morozov’s view: AI evolves through use, blurs into culture, and alters cognition, even changing the humans who seek to control it. He argues that socialism after AI must become a project of worldmaking—and produce new forms of collective life.

“A socialism worthy of AI cannot retreat to a clean division of labor in which politics decides and technology provides. It has to acknowledge technology as a primary site of collective self‑formation. The point is not to abandon the democratic composition of criteria, nor to romanticize chaos. It is to build institutions that treat collective existence as a field of struggle and experiment—one where new values, new abilities, and new ways of living are constantly taking shape.”

Beyond Arendt and Gramsci

The Primacy of Politics

Dylan Riley

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Hannah Arendt’s causal and classificatory account of totalitarianism—rooted in “social atomization,” classlessness, and mass movements—is frequently invoked as the key to understanding the rising authoritarianism of our time. But, as Riley shows, her analysis fails to withstand historical scrutiny. Instead, he urges us to look to the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, whose trenchant examination of civil society and hegemony provides a more compelling explanation of authoritarian dynamics. Movements like MAGA are best understood not as proto-totalitarian forces but as actors waging a Gramscian “war of position” within civil society.

“Perhaps the best way to grasp what is happening is to focus on the problem of politics. The real issue in the West today is not a threatened revolutionary rupture producing as its opposite a counter-revolutionary response, but rather an etiolation of the links between the realm of private and associational life and the realm of politics. This split created a rupture between political representatives and the groups that they were supposed to be representing: a fracture that was clearest in the Republican Party from 2015 on but that had its counterpart in the revolt of the Democratic Party’s new left. What is occurring now is an incipient restructuring of these links on the ground of a terrain that is still in the process of formation. The point is not about being “for” or “against” civil society, but rather about who will control the process of its political articulation.”

A Pure Act in a Dirty World

An Interview with Matthew Shipp

Leonard Benardo

The Ideas Letter

Interview

The great and ferociously original jazz pianist Matthew Shipp riffs with Benardo on what it means for a musician to find a truly personal sound—something deeper than virtuosity, rooted in instinct, risk, and a kind of “unlearning” of received rules. Shipp describes improvisation as an ability to draw on the subconscious, almost like speaking a language whose grammar lives in the nervous system. He observes that real authenticity comes from ruthless self-knowledge rather than from imitating heroes or chasing technical perfection. Influences, for him, are “food” to be digested and transformed.

“I believe all great art is the product of someone figuring out what it is exactly that they have to offer and then developing that particular universe to its ultimate form. So working with what God gives you is the ticket for everyone—and whatever God gives you as an artist with vision you can build a temple upon it. Trying to be like anyone before you is not the way to go. So trying to isolate what you do understand about the universe and then building off of that premise is what it is all about.”

Democratic Minimalism

Shadi Hamid’s America without alternatives

Oliver Eagleton

The Baffler

Essay

Eagleton reviews Shadi Hamid’s The Case for American Power, in which the author defends American global hegemony with the zeal of a convert. Hamid began his career deeply critical of American imperialism, but now embraces the country’s moral mission of spreading democracy and upholding international law. To defend his position, he adopts an unusual dualism—elevating America to an unimpeachable and abstract ideal while accepting (and forgiving) that it acts rather differently in practice. This allows him to defend U.S. global dominance, justify hypocrisy as virtue, and frame contemporary geopolitics as an existential civilizational struggle that only American power can rightly prosecute.

“… This viewpoint means that no crime the United States commits can possibly weaken one’s attachment to it. When the country blows up news stations in Kabul or small boats in the Caribbean, we are encouraged to see this as a betrayal rather than a revelation of its national essence. At which point we can relive Hamid’s moment of conversion in Amman, taking our anger as a sign of our investment in the motherland, and an impetus to improve it as much as we can.”

“A Place Where Freedom Means Something”

James Baldwin’s Global Maroon Geographies

Ida Danewid

Antipode

Journal Article

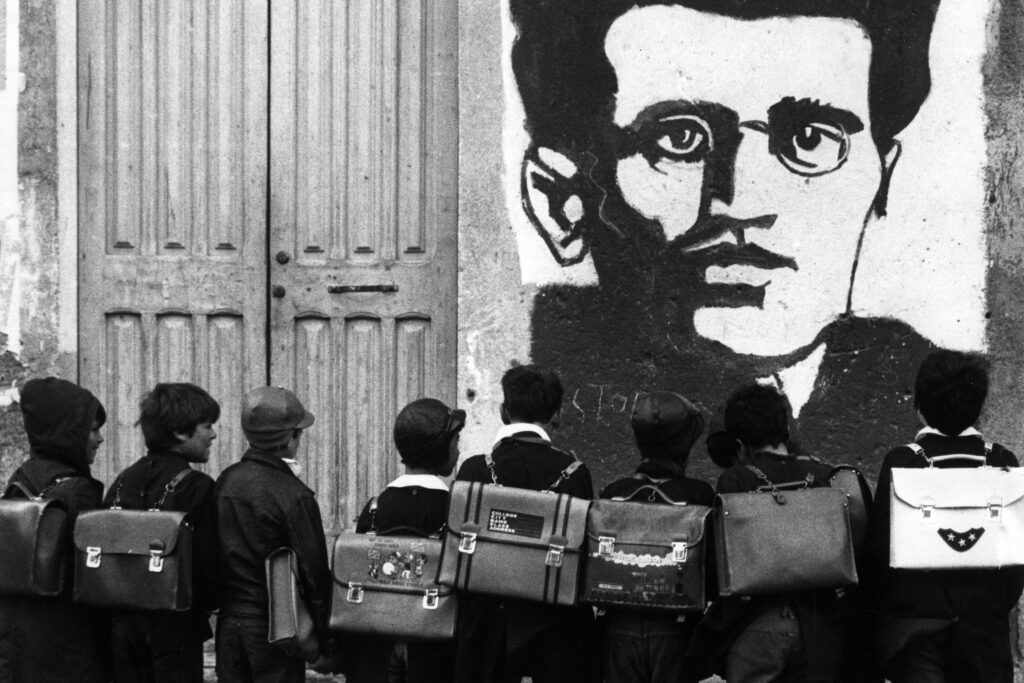

Although James Baldwin spoke out for the Algerian revolution, Palestinian freedom, and the fight against apartheid, he is often treated as a writer concerned mainly with U.S. civil rights and racial reconciliation. Danewid unsettles that familiar picture by challenging liberal readings of Baldwin and placing his work in conversation with ideas of decolonization, fugitivity, and life beyond the state. What emerges is a vision of “anarcho-blackness” that rejects the confines of the nation-state and instead imagines freer, less domesticated ways of living in the world.

“Indeed, the experience of living abroad made it increasingly clear that statelessness—a condition familiar to many black and other minoritised communities within the US—is a global phenomenon produced by the very entity meant to guard against it: that is, the nation-state. The solution, Baldwin would increasingly come to conclude, was not just to escape but to engage in new and creative forms of placemaking. In the same way that historical forms of marronage had been a process entailing both refusal and becoming, so Baldwin’s flight would come to take on a creative dimension, culminating in an anarcho-blackness …”

Is a River Alive?

An Interview with Robert Macfarlane

Darius Cuplinskas

New Books Network

Podcast

Robert Macfarlane discusses his new book Is a River Alive? with Cuplinskas. The book offers a lively, globe-trotting argument that we need to broaden our understanding of rivers by seeing them as living beings. He tells the stories of four river systems—in Ecuador, India, Canada, and England—where law, indigenous knowledge, and local activism meet. Rivers are not mere objects but vibrant beings with claims of their own. He shows how societies are pushing back against extractive development by recognizing the deep interconnection between forests, rivers, and human communities.

“So the central premise of the Selva Viviente movement is that the forest itself is a conscious, living being, and humans are part of that consciousness of that life. So is the water. So are the creatures, and that’s why it makes no sense to an oil company executive, let’s say, it makes no sense to a nation state minister in a conventional liberal democracy because it’s untranslatable into the idioms of those discourses. And the impressive thing is how absolute the Sarayaku people have been about maintaining the integrity of that central ontological claim: the forest is a living and a conscious being. They refuse its translation into standard conservation idiom. Oh, we should preserve the forest and not allow drilling there because we want to keep species abundance and species diversity at high levels.”