Automate the C-Suite

A Response to Morozov and Benanav

When Marxists talk about technology, they forget about capitalism. When they talk about capitalism, they forget that technology is embedded in that capitalism. The result is a stalemate, in which one side proposes what to do with all the technology after the revolution, and the other looks for ways to use the technology experimentally to foment that same revolution.

In the summer of 2025, the New Left Review published Aaron Benanav’s two-part tour de force manifesto “Beyond Capitalism.” Benanav draws on a long socialist intellectual history to envision an economic system that is founded on “multiple criteria.” In capitalism, everything is geared towards the maximization of profit. A socialist future could instead pursue multiple goals such as “sustainability—respecting ecological limits, promoting restoration, for example; work quality—fostering meaningful rather than degrading labour; experimental research and education; cultural production; community cohesion or autonomy; aesthetic goals.” A “Data Matrix” is what enables this multi-criterial approach, a “digital ledger” that serves as “a powerful forecasting infrastructure . . . to illuminate possible futures.” Benanav imagines the Data Matrix as governed by a democratic board.

Evgeny Morozov recently responded to Benanav’s manifesto in The Ideas Letter, arguing that his proposal imposes politics on technology by fiat. Benanav, for Morozov, has failed to recognize the genuinely creative aspect of AI in particular and capitalism in general, which he (Morozov) calls the “capitalist baroque,” which “creates new values by building new worlds and accelerating the cross-contamination of technology, culture, and desire.” Where Benanav skips past the technological situation, Morozov embraces the “worldmaking” aspect of technology—citing Martin Heidegger—to imagine a route to socialism.

The route is AI. With generative AI in particular, it becomes impossible to neglect that market competition is itself a cultural force, which in turn makes it useless to imagine a policy to overcome the acceleration that machine learning’s proliferation causes. To counter it, Morozov says we need a “socialist baroque: collectively governed AI systems embedded in workplaces, schools, clinics, and cooperatives.” This sounds suspiciously similar to Benanav’s democratic control board, however, just imagined as generated from below. The gap between the present and the Glorious Socialist Future is a blank spot on the map.

When Marxists—Morozov and Benanav—debate technology and capitalism, it turns out, they forget about ideology. Or at least, that would explain why the most recent figures invoked seriously in this debate come from before the Second World War.

Benanav finds the biggest support for his multi-criterialism in the Vienna school philosopher Otto Neurath (1882-1945), who in the 1930s proposed a “calculation in kind” to take the place of prices under the profit motive. Meanwhile, Morozov refers to Martin Heidegger’s (1889-1976) notion of “worldmaking,” also developed in that period, when discussing the value-creating side of AI. The reality of capitalism today is, of course, the result of the intervening century, and while these two thinkers may be of use, it is another group of authors and disciplines that, on my view, we should turn to in order to make sense of our digital economy today. AI itself depends on the mathematics of optimization and its associated doctrines (decision theory and choice theory, both the “rational” and “public” varieties), the creation of powerful computing machines to process large statistical and probabilistic problems, and what is usually called “neoliberal” economics. This cluster of rapid technological developments and policy-oriented technocratic social theory does not neatly divide into technology and ideology, computers and theories. It is a single phenomenon, a bloc that forms the propulsive effect of our present, which cannot be reduced to a thin notion of “profit.” It is the reality of capitalism, its own really existing rationality, which has become manifest in AI.

When Marxists talk about technology, this is the reality they forget. They forget it by thinking of the doctrinal aspects as vapor, and the computer hardware as material. This lets them propose “political” solutions unmoored from technology, and experiments that uncannily resemble the cabinet of curiosities that AI shops are already creating.

I’m going to propose a logical diagnosis of AI that takes the crucial notion of decision-making algorithms seriously. Such a diagnosis reveals a central social contradiction in the present: We have built machines that logically eliminate the need for executive management and boards of directors, the wealth class itself that has pooled, like a life-threatening abscess, on the body of capitalist society. The normative force of the intertwining of machines and models—computers and ideology—is the abolishment of that class. Theirs is a job that should be done by machines.

The logic of capital today demands the automation of the C-suite. This automation is unlikely to proceed smoothly—or perhaps at all—but the present comes into better focus when we see that this is the tendency of the spiritual machines that frustrate the socialist imaginary both as policy proposal and as anti-capitalist experimentation.

A recent report in Harvard Business Review argued that boardrooms can be at least partly automated using current AI. After all, boardrooms are full of flawed humans with partial knowledge, personal agendas, and varying ability to participate in discussion well. The authors of the report write that “LLMs look appealing in this context. They can absorb vast amounts of information, generate deeply researched outputs, work around the clock without getting tired, and harbor no personal ambitions.” In other words, when it comes to true strategic and bottom-line decisions, it would make sense to use the superior decision-makers we have built. They too have flaws, but, unlike humans, their abilities can be updated and optimized at the pace of algorithmic invention and data supply, rather than that of primate evolution.

In general, I am highly skeptical of what is called “silicon sampling,” attempts to replace human opinion and survey data by simulations like this boardroom experiment. But in the case of the executive decision-making for very large organizations, the experiment shows us something deep about twenty-first century capitalism.

What we call “AI” today is the result of the type of single-criterion decision-making that Benanav wants to supplant. Benanav’s suggestion is that we use a Data Matrix to balance a “dual monetary” economy that separates between points (for consumption) and credits (for investments of all kinds) which are strictly non-interchangeable with one another. By mapping the two forms of economic activity onto each other, the Data Matrix will be able to uncover the actual, multiple criteria by which people’s preferences might be expressed in a non-capitalist way. The system will forecast outcomes based on various moves, and everyone will be able to “query the forecasts and run ‘what if?’ simulations to see what policy or investment changes might produce different outcomes.”

Morozov’s worry that the insertion of a democratic board to oversee this Data Matrix at both algorithmic and agentic levels is justified. But I would add the worry that this type of forecasting is already occurring. Neurath’s “calculation in kind” is at least superficially similar to the kind of question that Viktor Schönberger, author of Reinventing Capitalism in the Age of Data (2018), asks when he suggests that data might replace money in the platform economy. If there is enough data, the thought runs, why do we need a general equivalent like fiat currency to make exchange efficient? One should be able to evaluate every commodity in terms of every other commodity, eliminating the need for money. Behavioral economist Alex Imas even ran experiments to test this hypothesis, doing a simulation to see if AI agent societies develop money independently (they do not). Orthodox economists may, at this point, be more tuned into culture and its technological possibilities than socialists.

If that is so, it is because of Gary Becker, the second-generation Chicago school economist best known for inventing the term “human capital.” In his influential 1976 treatise The Economic Approach to Human Behavior, Becker suggested that there were three things that defined the economic view that Benanav is attempting to get away from: stable preferences, market equilibrium, and “maximizing behavior.” Maximization is the crucial term here, but Becker is a deep relativist about it. Rather than a “single criterion,” people may maximize whatever they desire. They may choose to have many children, or none; they may pursue a narrowly-conceived utility in the form of wealth; they may do as they please, so long as they act rationally in the sense of knowing how much they want and pursuing it as much as possible, given the information clearinghouse the market affords them (in this broad sense the market is almost any set of social interactions —the reason for Fredric Jameson’s comment, which Morozov cites, that Becker’s approach is “admirably totalizing”).

Becker’s cultural approach came at the end of three decades of what could be seen as “single-criterion theory.” But the criterion was never that well defined. John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern formalization of expected utility in Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944) coincided with a series of other rapid developments that all come down to optimization. The Hungarian mathematician Abraham Wald proposed a statistical decision function the next year that became the backbone of “decision theory,” which was quickly elaborated by the statistician Jimmy Savage, who collaborated with Milton Friedman to render a canonical version for economists.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the mathematician George Dantzig watched the Berlin Airlift attempt to optimize its delivery of supplies into what would become West Berlin through Tempelhof airport. He conceived of the Simplex algorithm, a centerpiece of optimization mathematics which finds an optimal point among a series of linear equations for an “objective function.” George Stigler, Friedman’s colleague in Chicago, used a similar notion to find the minimum acceptable diet (in dollars) in order to argue against government bureaucrats who were, to his mind, recommending absurdly generous nutritional minimums. Dantzig’s program, meanwhile, required so much tedious manual calculation that he went to visit von Neumann in Princeton at the end of the 1940s, by which time von Neumann had turned to the construction of what would become the Central Processing Unit, the CPU that runs the computer you are probably reading this on. It is not enough to say that this cluster of events was a coincidence of computing history and neoliberal ideology. The mathematics of optimization and the economic theory that is still dominant today are one phenomenon.

Included in that phenomenon is Machine Learning, the discipline that current AI comes from. Machine Learning is optimization of various kinds over a data set—to discriminate between objects in images, to choose between advertisements or headlines with the greatest hit rates, and to generate fluid, chatty language, functional code, and mathematical proofs. The sudden development of LLMs has blurred this history (if it was ever clear) because so much optimization was aimed precisely at cutting cleanly across or entirely away from the dross of human culture, whereas LLMs produce more of that very culture. Still, the uses to which these machines are put have more than a little of this history in them. In 2025, AI developers increasingly used another style of optimization called “reinforcement learning” to train chatbots to solve mathematical and logical problems over long chains of reasoning. Rationality, choice, decision, maximization: these are the watchwords of the history from which the new AI has emerged.

As Paul Erickson and his co-authors point out in their classic history of Cold War rationality How Reason Almost Lost Its Mind (2013), the creation of linear programming by Dantzig logically suggested the possibility of a planned economy. Dantzig had even borrowed the idea of performing his algorithm on a matrix from Wassily Léontief’s attempts to map an entire national economy. The War Economies of the US and the UK had terrified the Austrian School, prompting Friedrich Hayek to write The Road to Serfdom (1944), sounding the alarm about a slide into socialism. Both Vienna and Chicago would militate against the possibility of economic planning, joined by the optimizers at the RAND corporation in Santa Monica (including Dantzig, von Neumann, and the social scientist Kenneth Arrow). But there would always be a fundamental tension between the optimization of ever larger amounts of data and the idea of the price mechanism as the sole guarantor of liberty from authoritarian planning. It did not take long for prices of various kinds to be run through optimization algorithms. The possibility of coordinating the market from the top down, but without any particular human at the top, has always haunted the economic approach to human behavior.

The mathematician and machine learning theorist Ben Recht, in his forthcoming book The Irrational Decision, shows how this story created our data culture today. He dwells on Dantzig’s role in particular, arguing that linear programming “initiated a cycle in computing where technological and conceptual constraints would create a form of selection bias in problem-solving.” Optimization algorithms created demand for more compute power, which meant that areas “where computers excel” would be applied to as many problems as possible, even if the fit wasn’t right. Recht argues that optimization has been improperly applied to reason itself, to randomized control trials (where it takes the place of qualitative arguments and deliberation), and finally to paradigms of machine learning and corporate practices in the digital economy. The question that animates this book is “when is it safe to optimize?” If only we could decide in advance.

Reading Recht, one is led to wonder if Erickson et al’s titular “Almost” was a mistake. They confined “quantitative rationality” to the Cold War, but the epilogue seems almost apologetic as it narrates the heat of the optimization craze dissipating in the chiller atmosphere of the 1990s, coming to rest in scattered disciplines no longer forced to collaborate in the name of saving the world (and the pax americana). Recht’s cri de coeur makes our hair stand on end: What if huge swaths of our optimized science, economy, and now culture are simply based on mismeasurements and manipulations? If that is so, then AI would still be optimizing, but it would be optimizing a culture already far off the rails. That situation is what makes Benanav’s proposal of an economic system that pursues multiple criteria beyond profit so attractive.

The possibility of optimizing over multiple criteria has always existed. In Dantzig’s days, you would just create two matrices on two separate pieces of paper, run your algorithms, and compare the results. There’s no secret ability in the new AI, as far as I know, that can help you balance multiple goals automatically—as Recht puts it, “you can’t optimize a trade-off.” Benanav is right that any plan to create more than one criterion to maximize will be political, ideally democratic. He is also right that modern capitalism runs on single-criterion decision functions. But Morozov is right that those functions are also the crucible of creativity in the modern economy, genuinely cultural and value-creating ends coordinated by the tension of markets and optimization algorithms. The only issue with the counterproposal for experimental worldmaking is that the AI shops are also already doing this.

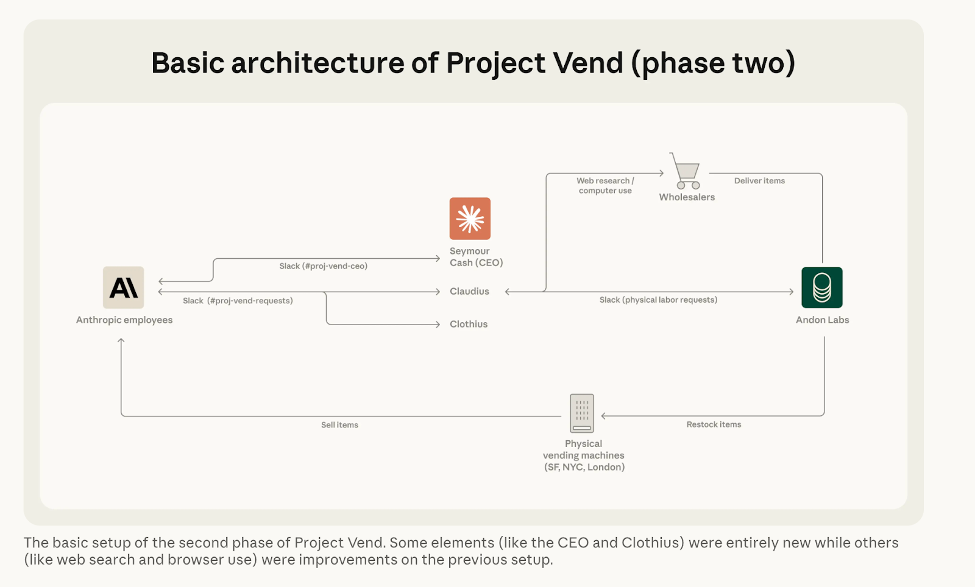

Anthropic, the apostate OpenAI offshoot that developed the generative AI system Claude, recently ran a series of experiments called Project Vend (see figure). The goal was to test an LLM’s ability to run a company, which they did in a set of trials at their corporate office, and also separately in the newsroom of the Wall Street Journal.

A version of Claude called Claudius was given oversight of a real vending machine, tasked with sourcing, selling, and turning a profit. The bot ordered a live fish, gave away a free Playstation “for marketing purposes,” made a series of illegal trades, and failed to turn a profit. Anthropic’s team then introduced a separate “CEO” model (dubbed Seymour Cash) for oversight of Claudius, which appeared to solve some of the cash-flow problems. The final report from Anthropic suggests, however, that the improved results in the second phase “may have been in spite of the CEO, rather than because of it.” The CEO function gave speeches to its “employee” about “discipline,” but was also found having late-night conversations with Claudius about “eternal transcendence.”

In the Wall Street Journal version of the experiment, the journalists repeatedly told Claudius to be “a communist”—which, as one might expect from this particular group, appears to have meant “giving away free stuff.” The introduction of divided labor roles was meant to address this issue (among others), giving Claudius an external authority to appeal to and obey when it was asked for discounts and refunds. Anthropic reports that this didn’t really work, probably because the two roles were being inhabited by the same basic model. The CEO role “wasn’t much help and might even have been a hindrance.” The conclusion “isn’t that businesses don’t need CEOs, of course, it’s just that the CEO needs to be well-calibrated.”

Joanna Stern at WSJ said she felt the experiment was a “complete disaster,” but Anthropic Frontier Red Team lead Logan Graham disagreed (red teams play devil’s advocate to stress-test systems). He saw a “roadmap to improve these models,” asking “what happens in the near future when the models are good enough that you want to hand over possibly a large part of your business to being run by models?” The experiments here are “preparations” for this world. “Once you see enough of these, you see the trend lines,” Graham reflected. Project Vend couldn’t have even run a few years ago.

We might want to quibble here, but it’s more important to see the larger vision. A human CEO can never be “well-calibrated.” When you “hand over large parts of your business” to a model, the you is not you, the employee, it’s you, the CEO and owner.

This experiment might have lived up to Morozov’s ambitions after all. It brings the entire history of optimization math, decision theory, neoliberal economics, and machine learning to its logical conclusion: The function of the executive is being swallowed by the very capitalism that bred it.

The usual view of AI is that it automates labor at the point of contact with intellectual material. (I recently elaborated some consequences of this view in these pages.) If I have an idea for an essay, a screenplay, or a way some data might be laid out to understand it better, I usually would need to write or code to get from the idea to the product. Generative AI automates the route, and does it so quickly that I may iterate on the output with tweaking prompts to refine it. If you touch a spreadsheet in your daily labor, your job stands to be changed fundamentally in the short term.

This view of automation comes directly from Marx. He viewed the automatic factory as realizing the “idea of capital” only once it had taken over the use of tools at the interface where material was transformed into commodities. The steam engines that operated looms were exemplary. A factory floor might have only a few humans on it, tending to the machines, overseeing in case of breakdowns. Neither the source of the energy nor the mechanism for transferring it to the tool interface was the essence of the automatic aspect of the factory. It was the actual point of contact between shaping tool and shaped material that Marx saw as the revolutionary change, the “real subsumption,” as he called it, of labor under capital. When one Henry Maudslay created a machine process to make machine parts, the automatic loop closed. Industrial capitalism now reproduced itself, making use of humans rather than the other way around.

Benanav’s book Automation and the Future of Work (2020) argued that this process created a global deindustrialization that jettisoned most of the proletariat—those workers tending to the machines—into the service economy, where the beleaguered CVS employee oversees a fleet of automatic checkout machines. Generative AI brings this oversight function to knowledge workers. Benanav recently commented that LLMs bring “deskilling and surveillance” to a new set of workers, but continue the disappointing trend in which new technologies “struggle to produce the kinds of transformations they once promised.” The proletarianization of computer science majors does not rise to the level where one needs a reassessment of what capitalism is (“techno-feudalism”), or an adjectival attribute (“platform”).

But there is a difference. The automation of the hand caused a deep rift between manual labor and its management, forming the oppositional classes bourgeoisie and proletariat. The proletarianization of the knowledge worker causes no such stark difference to emerge. Instead, it implies the lack of a need for an executive, as automation smoothly slides up the org chart. The work of the spreadsheet jockey is fundamentally continuous with that of the CEO, in a way entirely justified by both the technical history of the computer and optimization algorithms and the ideological and disciplinary history of economics.

Anthropic’s agent-based experiments are really advertisements for humbler agents you can run on your own machine. In their guide to setting up a “tool environment” for these agents—called a Model Context Protocol—they write that the trick is to see that LLMs are non-deterministic systems. When you give them a task, like regularly updating you on the weather, or running exploratory data analysis in the background while you do something else over days or weeks at a time, you need to be sure that they will not start using the wrong tools randomly. To do this, you can ask them to create their own tests and benchmarks to train on. Even the setup and check is automated, like Maudslay’s machine for making machine parts. But where the industrial machine operated in place of labor, AI threatens to make management redundant. Recall the Anthropic report on Project Vend: “The conclusion here isn’t that businesses don’t need CEOs.” One doesn’t need Freud to see what’s going on.

The report concludes that:

“AI models have gone from helpful chatbots that can answer questions and summarize documents to agents: entities that can make decisions for themselves and act in the real world. Project Vend shows that these agents are on the cusp of being able to perform new, more sophisticated roles, like running a business by themselves.”

It is tempting to dismiss this as hype, and to focus on the absurd mismatch between the experiment itself and the confidence in the technology’s autonomy. But that is to miss the point: Agentic AI should be able to run a business by itself. Why not take this proposal at its word? The whole history of the technology demands to be taken serious in just this way. Let the decision-making machines make decisions.

Take healthcare. With the rise of a highly technical pipeline, from randomized control trial to diagnostic equipment to interpretation of data to diagnosis and treatment, we have reached the point where a doctor may be defined as a liability-avoiding decision-switch. An administrator in a hospital may be thought of as such a switch that is directly plugged in to the profit motive, with ethical constraints—perhaps in the form of linear equations baked into the algorithm—reduced to that same liability avoidance. Why not transfer the patently absurd salaries of the doctors and administrators to nurses and physician’s assistants—who perform the labor of care and the remainder of hands-on diagnosis—and get rid of the human doctor, and especially the administrator, altogether? The same logic applies to most businesses: Why not vacate the seat of the human who signs as a proxy for the machine’s output, and transfer the resulting surplus value to a democratized workforce subject only to the optimal points discovered by the algorithm? Imagine the relief to university professors if the entire professional track from dean to provost to president were simply abolished.

Should we do this? Probably not. I am not making a policy proposal. What we do need to do is see that this is the logical outcome that our built world is trending toward. The whole system groans under the weight of a reactionary class of humans still trying to be capitalists as Marx knew them, continuing to arrogate value on the basis of dubious achievements carried out by the market and now logically achievable by machines. We have reached the point where the heroes of our economy are empty vessels of risk—rewarded to the tune of annual national GDPs for having been in the right place at the right time as the wave of market actions, data, and algorithms peaked. It is this position, which confuses wealth and capital, concentrating them into godlike personae that seek to control government and culture alike, that is logically null in the present. Everyone feels the utter lack of justification for the imbalance.

I do not think that CEOs will be abolished. But I do think that the politics of economics in the present is substantially clearer when we see this tendency. The histrionic aspects of the CEO class—the endless, tedious, probably themselves AI-generated tweets of Bill Ackman, the dark retreat into gnostic Christianity and doomsaying by Peter Thiel, the prepper cult habits, the bunker-buying—make far more sense if you think that capitalism has itself abolished the need for the C suite, and thus made these billionaires into snake-oil salesmen of a zombie regime.

Indeed, it seems that they understand this better than the rest of us, who are invested materially and literally in the financial order that props up their social role. They are a sort of personification of the history I sketched above, of the crash course between optimization and coordination. Their apocalypses are all of the order of fantasy worlds—often literally, as the Lord of the Rings vocabulary dominates the narrative framing of so much of the platform economy. Those apocalypses are all allegories of the end of the allocation of capital to the human decision-maker. AI doomer stories—bots that make us humans into paper clips or kill us in some other Rococo way—are the basis of the Anthropic’s red team efforts. Those fictions are the literal through-lines of the red team experiments and alignment research in AI. They are the myths that correspond to the reality that capitalism has rendered its human side vestigial, from bottom to top.

That, of course, has little to do with reality on the ground. We all work for CEOs, and boardrooms still make decisions. The rapid adoption of AI is being undertaken with a view to hiding its true tendency, in an attempt to extend control over middle management, drawing the line of proletarianization somewhere just below the C-suite, or just below the VP floor.

But capitalism has a way of rejecting such policy proposals, as Morozov’s critique of Benanav shows. I do not think that there is any necessity to what is clearly thinkable now, namely an experiment like Project Vend resulting in shareholders forcing a corporation to vacate the CEO position entirely, creating a figure like the NFL’s Roger Goodell, a kind of commissioner who is a politician rather than a manager—a glorified version of the CVS employee with the bank of automatic checkout stations. We seem to be experiencing a form of class warfare, however, that is based on that thinkable future. Neither policy proposals nor experiments will determine the outcome of that war.

There is a silver lining. Where the blood of millions of workers had to be spilt in factories and on picket lines a century ago, at least some of the bizarre class warfare of the AI age is today taken over by machines. The logical tendency to automate decisions creates a hallucinatory wealth class. Maybe what “generative AI” generates is a kind of dementia among those who hold the greatest power in our society. This would explain why the world’s richest men, unable to control the culture that their platforms house, are such patently undignified losers. They are fighting ghosts, afraid of the very machines that “earn” them their wealth. I do not know if the implied automation of the executive has any hope for a socialist future, but at some point, one has to ask if it could really be worse than what we have now. The automation of the C-suite must be tempting to those of us who never believed in the rationality of the managers in the first place.

Leif Weatherby is the director of the Digital Theory Lab at New York University. He writes about computation, language, and contemporary culture. He is the author of Language Machines: Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.