The Socialist Charcuterie Board

Morozov Replies

Aaron Benanav has issued his rebuttal, and what a curious document it is. He accuses me of misreading his arguments—of misreadings so egregious, so howlingly obtuse, that one might expect him to produce the damning evidence with prosecutorial relish. Alas, the smoking gun remains holstered. The misreadings Benanav conjures are indeed spectacular; they’re just not mine. My actual charges sit untouched, like hors d’oeuvres no one thought to pass around.

Since Benanav prefers paraphrase to citation, allow me to do the heavy lifting for both of us. Here is what I actually wrote about the supposed crux of his complaint, the plasticity of values in his system:

Benanav insists that values are not fixed. Drawing on the Austrian polymath Otto Neurath, the American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey, and others, he argues that priorities evolve through conflict, learning, and experience. Plans must be revised, criteria adjusted, and institutions rebuilt in light of what happens. Socialism, in his picture, is inherently experimental.

Benanav, by some feat of hermeneutic alchemy, twists this into its opposite. Having constructed a straw man of convenient dimensions, he proceeds to pummel it with vigor. Thus his complaint: “Morozov mischaracterizes my framework as requiring society to determine its values in advance, assign them weights, and then apply them administratively to govern economic life.”

One rubs one’s eyes. Is this what I’m saying when I credit him with “emphasizing that values evolve”? When I write that “Benanav hopes that multi‑criterial composition—the continuous re‑weighing of efficiency, ecology, care, free time—would generate the kind of dynamic responsiveness that older forms of socialism lacked”? Am I misreading Benanav’s penchant for socialist weightlifting when his two New Left Review essays evoke the need to “weigh possible efficiency gains alongside other values,” to “weigh multiple incommensurable aims,” to “weigh legitimate but often incompatible priorities,” and to “weigh [criteria] against each other”?

I even stand charged with recasting his framework, “designed to organize conflict over investment,” as “a system of administrative closure that would prematurely discipline experimentation.” The audacity! Except that I also call his socialism “inherently experimental,” built on conflict, thriving on revision. One struggles to misread a man in quite the way he claims when one’s own sentences keep getting in the way.

Much of Benanav’s defense rests on a claim that sounds reasonable enough: Values don’t simply parachute into Investment Boards from some normative stratosphere. They are, he now assures us, “clarified, contested, and recomposed over time as societies act, confront consequences, and revise their commitments in light of what those actions reveal or transform.” One nods along—until one notices that this freshly minted sophistication is largely absent from the original essays. To be fair, those essays contain scattered gestures toward dynamism: “Values are not fixed inputs to the system,” Benanav writes in his first NLR piece. “They enter into argument, take shape through selection and are redefined by the accumulation of decisions.” But how? Through what mechanism does “the accumulation of decisions” redefine values? Of this we hear nothing. The assertion floats free of any sociological machinery, not even the mildest Parsonian hum: No theory of action, no account of how to reconcile system and agency, no discussion of ideology. Just Investment Boards on one side, deliberating and executing allocations, and a Free Sector on the other, incubating values.

The crudity in the distribution of labor between the two is not my freewheeling interpretation. Here is Benanav in his second NLR essay: Unlike Investment Boards, “which allocate resources based on assessed social priorities, the Free Sector is governed by a different principle: the right of individuals and groups to explore and develop ideas, movements and institutions without needing to justify themselves in advance.” Same essay: “Free Associations serve not just as value carriers but as value creators.” The architecture is clear: Values are born predominantly (but, apparently, not exclusively) in the Free Sector, then shipped downstream to Investment Boards for deliberation and implementation. And yet—curiously, suspiciously—both the Free Sector and the Free Associations have vanished from Benanav’s elaborate response. The engine room of his entire system, and he neglects to mention it.

Even the language that does appear in those essays betrays a passive, revelatory model rather than a transformative one. “Social values,” Benanav writes, “emerge dynamically through the pattern of investments over time, revealing which priorities the Investment Boards—and the broader public—consider most important.” Revealing—not generating, not transforming, not constituting. The verb does the quiet work of a revealed-preference framework dressed in socialist clothing: Values pre-exist; decisions merely disclose them. Elsewhere, Benanav specifies the direction of causation with unfortunate clarity: “Values shape economic outcomes dynamically, through the decisions people make.” Values shape outcomes—but do outcomes shape values? Of a reverse flow, from production back to the Free Sector, from material practice to normative transformation, the essays offer no account whatsoever. “Democratic life in the Free Sector ensures that society is always open to internal contestation, collective learning and political renewal”—but this influence runs toward politics, not back from the functional economy. The pipeline has no return valve.

Investment Boards, he writes in one of the two original essays, “allow other values to be brought to bear in shaping the production process.” Brought to bear—as one brings a tool to a task, an external instrument applied to inert material. But what of values discovered in production? Emergent from it? Benanav’s firms may “learn from one another” about which trade-offs work—but this is empirical updating, not value transformation. They navigate among values already on the menu; they do not cook new dishes. The omission is not a slip—it is structural. By betting on competing firms as the vehicles of socialist deliverance, Benanav smuggles efficiency back through the servant’s entrance. The one capitalist criterion that matters, arriving without a passport. I’ll return to this point, for it’s the trapdoor through which his entire framework falls back into the capitalist imaginary it claims to escape.

And lest anyone suspect I’ve imposed an artificial rigidity on Benanav’s value-pluralism—efficiency, ecology, care, free time, arrayed like items on a socialist charcuterie board—let me be clear: This is his menu, not mine. “Pursuing ecological sustainability may come at the cost of living standards or food production; prioritizing care may reduce efficiency gains.” I’m simply reading the list aloud.

The remainder of Benanav’s response exhibits an evasive choreography that is familiar: Sidestep the large questions, plant your flag on the small ones, declare victory. Five paragraphs—five!—are devoted to demolishing the claim that Investment Boards would “operate as an overbearing procedural constraint on innovation.” The demolition is thorough, even impressive. There is only one problem: I never made the claim. Here is what I actually wrote:

Now imagine a future in which a multi-criterial Investment Board, under pressure to avoid bias and misinformation, mandates that AI systems be fair according to agreed metrics, respect privacy, minimize energy use, and promote well-being. Call this woke AI by democratic mandate—an infrastructure whose outputs are correct, diverse, and balanced. Yet it still feels like it was designed over our heads.

The point is not about innovation. The point is about alienation—the phenomenological chill that sets in when values, however noble, arrive prepackaged from distant committees. As they migrate from Free Sector to Investment Board to firm to user, something drains away. Call it legitimacy; call it ownership; call it the difference between a value you’ve fought for and one stamped on your forehead at the end of a long institutional conveyor belt.

Benanav misses this entirely. Having fashioned a more convenient target, he’s off to the buzzword races—“blitzscaling” here, “enshittification” there, a pleasant tour of platform pathologies. Meanwhile, the core objection sits unattended: the longer the chain from value-making to value-living, the thinner the thread of meaning that connects them.

The misreadings do not relent. Benanav even claims that I pit “local experimentation and collective control as opposing principles.” Here is what I actually wrote: “The point is not that these examples are the answer, but that a socialism worthy of AI would institutionalize the capacity to try such arrangements, inhabit them, and modify or abandon them—and at scale, with real resources.” Institutionalize. At scale. With real resources. Elsewhere in the essay, I contend that the task of the left should be to “build institutions that treat collective existence as a field of struggle and experiment.” Collective. Experiment. Apparently all these phrases were too faint a signal, too cryptic a code. The local-versus-collective dichotomy Benanav attributes to me is, like much else in his response, a phantom of his own conjuring.

Before I clarify what my original essay actually intended, let me correct Benanav’s handling of cybernetics. His unfamiliarity with this intellectual terrain is evident: “Cybernetics is a theory of systems that detect deviations and restore coherence in response to disturbance. Even in Stafford Beer’s most sophisticated formulations, the core concern is not innovation but viability: maintaining a system’s identity under changing conditions… As a research program, cybernetics has also long since been exhausted.”

One hates to disturb such serene certainty, but the cybernetic canon also includes works celebrating “deviation-amplifying systems” and “heterogenistics”—not exactly your average conservative defense of equilibrium conditions. Not to mention that one of cybernetics’s founding fathers—Warren McCulloch—co-authored the seminal paper on neural nets, the cornerstone of today’s Large Language Models (LLMs). Perhaps all those McCulloch-worshipping AI scientists are toiling in blissful denial of just how exhausted Benanav finds their paradigm.

As for Beer: His obsession was never viability as mere survival, the dreary persistence of a system that simply refuses to die. It was a restless, self-reinventing viability, one capable of absorbing the ever-proliferating variety of the modern world and transforming itself in the encounter so that, to quote Beer himself, the system would become “capable of adapting smoothly to unpredicted change.” Beer, ironically, would have recognized a kindred spirit in Benanav’s own hero, Otto Neurath, he of the boat perpetually rebuilt at sea. For all we know, he might have even admired a contemporary socialist who has just penned an essay championing “permanent macroeconomic stability” as socialism’s crowning achievement. (The identity of this thinker I leave as an exercise for the reader.)

Lastly, my own engagement with the technology projects of early-1970s Latin America was driven by a desire to rescue that history from the dusty clutches of historians and sociologists of technology—to plant it where it belongs, in the debates over technological autonomy that animated dependency theory. Had Benanav lifted his gaze from the footnotes of the Global North, he might have noticed that something resembling the centerpiece of his system, the Data Matrix, was proposed—and partially implemented—under the name “numerical experimentation” in Venezuela, Argentina, and Peru half a century ago. So much for the barrenness of alternative research programs. The seeds were planted long before Benanav thought to claim the harvest.

My original essay posed three questions that generative AI has dragged, kicking and screaming, into the socialist spotlight—questions of strategy and desire, not institutional plumbing:

- Can socialism offer a better way of living with generative AI than capitalism does?

- Can it deliver a form of life worth wanting, rather than a fairer share of what capital has already built?

- What would it take to transform the macro‑institutional imagination so that socialism appears as a wholesale, systemic alternative—and not as a procedural fix applied to capitalist dynamism?

These are not decorative questions. If socialism is ever to beat capitalism—at the ballot box or the barricades—it must compete on the terrain where capitalism now harvests its deepest legitimacy: the promise of expanded agency, intensified creativity, worldmaking powers distributed (however unevenly, however cynically) into the texture of everyday life.

This is the techno-solutionist infrastructure that props up capitalism not as an economic system but as a form of life and a religion. The old Cold War quarrels over allocation—market or plan, which calculates better?—have faded into period pieces, quaint relics of an era when legitimacy still trafficked in efficiency claims. Today’s capitalist liturgy runs on a different fuel. This is why Leif Weatherby’s vision of CEOs getting replaced by algorithms strikes me as science fiction of the purest strain: I’ll believe it the moment an AI system sweet-talks the rulers of Saudi Arabia into cutting it a billion-dollar check. The CEOs of OpenAI and Anthropic secure those signatures because they’re in the business of narrative, ideology, mythology, and meaning-manufacture; management is the least consequential thing a modern CEO actually does. (Otherwise, I’m always glad to be lectured about the realities of contemporary capitalism by a scholar well-versed in German idealism, romanticism, and media theory!)

Benanav seems blissfully unaware of any of this, happily rehashing the Socialist Calculation Debate of the 1930s as if we all still had much to learn from the short-lived experience of the Bavarian Soviet Republic (the context for Neurath’s original interventions on the subject). He takes evident pride in reconciling Marx and Keynes—a diplomatic achievement, no doubt. (I, in contrast, think the real task of the left is to reconcile Marx with Marx, and to do so by deepening his ties to Hegel; but that is a different essay.) This nostalgic orientation explains why Benanav’s own questionnaire is organized around the problem of how to allocate scarce resources across competing uses under ecological constraint—the socialism-as-rationing-board that haunted Hayek’s nightmares, now rebranded as vision.

And he answers it with many pages of intricate design: Investment Boards, matrices, criteria, trade-offs—an institutional terrarium of exquisite complexity. Paired, however, with a striking silence about political strategy. How does any of this become plausible? Contestable? Lovable? Winnable? The practical mechanism of transition hovers somewhere between apocalypse management and an unspecified rupture, a deus ex machina that never quite descends from the rafters. That omission is not incidental; it is diagnostic. A framework that cannot say how it would generate legitimacy and ideological purchase is not realist. It is institutional science fiction with politics—apart from all the handwaving about “conflict”—blacked out.

But despair not: With so much to sift through, we can still extrapolate Benanav’s position on my three questions. On the first two—better life with AI, and a form of life worth wanting—he offers not answers but architecture. His essays are remarkably silent on what makes this socialism desirable, what forms of flourishing it enables, what anyone would fight for. The only motivating force discernible in the text is negative: ecological collapse, resource limits, the end of growth. Strip away the procedural machinery and what remains is a wager: that climate catastrophe will make the positive questions unnecessary, doing all the dirty ideological work for him. This is a long shot. Worse: It is a surrender. It cedes the terrain of technological imagination to the Thiels and the Musks of the world, whose entire business model is turning constraint into myth and accounting into destiny.

Put vulgarly: When asked to choose between colonizing Mars and deliberating over whether to turn off the lights in the toilet or the living room, I suspect most people will choose going to Mars. Not because they are fools, but because that vision promises new worlds and expanded capacities, while the other promises a series of never-ending meetings about how to divvy up the dwindling pie. Oscar Wilde might as well have been drafting the epitaph for Benanav’s multi-criteria economy when he proclaimed that “the trouble with socialism is that it takes up too many evenings.” Benanav’s socialism doesn’t just take up evenings; it transforms them into a permanent seminar on thermodynamic limits.

This is where his rebuttal reveals more than it intends. Benanav treats my appeal to “worldmaking” as a romantic intoxication with novelty, the starry-eyed swoon of a man seduced by shiny objects. But worldmaking was never an ode to gadgets. (Nor, by the way, was it a paean to Heidegger, as Weatherby surmises: I namecheck Heidegger exactly once, in the context of claiming that socialism needs to pose its own “question about technology,” and I explicitly state that he would not have subscribed to anything that followed. One mention to Heidegger does not a Heideggerian make. My actual intellectual debts over worldmaking—as an impure, always-changing mix of the material and the cultural—would span a rather eclectic pantheon of thinkers: Cornelius Castoriadis, G.L.S. Shackle, György Márkus, Evald Ilyenkov, Marshall Sahlins, to name just a few.)

Worldmaking names contemporary capitalism as it actually operates: a fusion of technology, finance, myth, religion, institutional improvisation, and mass affect that has bulldozed the tidy borders between “the economic,” “the political,” “the cultural,” and the intimate texture of everyday life. Late capitalism did not respect the modernist separation of spheres; it drove a wrecking ball through the lot—something that I pointed out in a long section on Fredric Jameson, which, despite his NLR-proximity, Benanav chose to ignore in its entirety. AI accelerates the demolition, turning the rubble into raw material for new constructions.

Benanav’s framework, by contrast, presupposes that the separation can be restored—that the genie can be coaxed back into its respective bottles. Firms innovate inside a functional economy; values are mostly manufactured elsewhere and then fed into the allocative apparatus of Investment Boards like ingredients into a sausage grinder; deliberation disciplines production from a safe administrative distance. The process is coherent on its own terms. It is also increasingly mismatched to the terrain on which legitimacy is actually manufactured—a terrain where the sausage grinder has been replaced by something stranger, faster, and far less interested in neat compartments.

Benanav dubs his project “a real political economy of technology,” but leaf through the inventory and you’ll find the merchandise has been smuggled in, price tags still attached, from the very warehouse Marx spent his life trying to burn down: efficiency, innovation, trade-offs, even such neoclassical curios as the “vintage problem” and the “production frontier.”

So when he asks why I decline to do that kind of political economy, the answer writes itself: My reading of Marx—partial, perhaps; flawed, possibly—is that the task was to dynamite the categories of political economy, not to embalm them in scholastic amber and slap “realism” on the display case. That a prominent Marxist economist can wield these terms as if they were neutral instruments of reason rather than historical artifacts marinated in capitalist brine tells you something melancholy about the state of the tradition. The tools of the master’s house, lovingly polished and passed off as revolutionary furniture.

Sadly, Benanav knows exactly what he’s doing. In a footnote to his first NLR essay, he explicitly dismisses the work of German value-form theorists—who argue that the categories of political economy (value, money, labor, the firm) are not neutral analytical tools but historically specific forms of capitalist social domination, to be abolished rather than repurposed. He doesn’t mention Moishe Postone—who chided socialists for fetishizing the category of “labor” instead of finding ways to transcend it—nor Simon Clarke—who argued that the categories of political economy, so skillfully dissected by Marx, are not neutral analytical tools passed off as timeless truths but, rather, reified expressions of social relations. We can infer that Benanav would find their work impractical too. Perhaps, it’s in the name of practicality that he himself operates with a conceptual apparatus that wouldn’t be out of place in a World Bank report.

Consider the value Benanav treats as most self-evidently balanceable: efficiency. Nowhere does he betray the slightest suspicion that efficiency might be culturally, politically, or socially constituted—that it names one historically specific way of exercising rational mastery, umbilically tied to the enterprise, the factory, the competitive firm, and the accountant’s unblinking stare. (For a solid sociological account of how to think of efficiency otherwise, see Jens Beckert’s classic text.) Quite the opposite: Efficiency arrives dressed as a quasi-scientific magnitude, ready to be measured, optimized, maximized, and then politely balanced against other values.

But here’s the rub. In capitalism—and in any post-capitalism foolish enough to inherit capitalism’s grammar—those other values (care, sustainability, equality) are themselves constituted as efficiency’s remainder: its outside, its damage, its collateral. Their very meaning is forged in the fires of what efficiency excludes. You cannot balance what has already been subordinated in the act of definition.

So what does it actually mean for enterprises under the command of Benanav’s Investment Boards to balance efficiency, care, and sustainability? Strip away the procedural filigree and the answer is almost tautological: Efficiently pursue efficiency. Efficiently pursue care. Efficiently pursue sustainability—in whatever proportions the Demos, after extensive deliberation, finds acceptable.

All of this flows quite naturally from Benanav’s setup: By tethering institutional survival to “real budget constraints” and policing the boundary with the threat of receivership, he ensures that the firm’s primary relationship to reality remains one of mandatory economization—i.e., that everything the firm does, including “care” and “sustainability,” must first pass through the grid of cost-accounting to become visible at all. Under the shadow of the points-ledger, the “multi-criterial” objective is never an escape from efficiency, but merely a more complex way of being disciplined by it.

Thus, for all Benanav’s claims to be building a multidimensional economy, what emerges from his elaborate theorizing remains decidedly one-dimensional. How would we even know what it means to pursue care caringly rather than merely efficiently? Or to pursue sustainability sustainably? To pursue care sustainably, or sustainability caringly? Here language starts to buckle, and for good reason: We genuinely do not know, because the forms of life out of which such practices might emerge—the soil in which they become legible as values in the first place—are not merely peripheral to Benanav’s system. They have no address there at all. No mechanism exists for them to germinate inside his firm-centric economy. They are, at best, tourists.

His Free Sector can host a thousand experiments among artists and activists, a carnival of alternative values blooming in the margins. Lovely. But for any of these hothouse flowers to gain purchase in the functional economy, they must first be dried, pressed, and laminated—rendered comparable, auditable, commensurable. Streamlined into an apparatus whose native tongue is efficiency, because its primary institutional form remains the firm (even if Benanav expands its definition to include “all producers, whatever their scale or structure” such that “firms are understood as institutions that convene people… to fulfil some socially identified need or desire.”) The firm: that sturdy little box into which all of capitalism’s creativity was once stuffed, and into which Benanav now proposes to stuff socialism’s as well.

Benanav waves all this away. My critique, he writes, shows I cannot “think through what a real alternative political economy would require”—I’m left with “no strategy,” only gestures and aspirations where institutions should be. But this assumes that the task of socialist theory is to make a fixed set of conceptual ingredients—firms, investment, labor, budgets, efficiency—cohere into an elegant framework. If the ingredients themselves are compromised, making them fit is not rigor but scholasticism. I have no desire to be a monk in an eleventh-century monastery, reconciling Aristotle with Scripture through ever more ingenious glosses. If the categories are broken, no amount of institutional embroidery will redeem them.

What Benanav mistakes for strategic naïveté is actually my refusal to gallop across philosophical terrain he seems not to recognize as treacherous. He remains nonchalant about questions that Marxists have taken for granted for far too long—questions I had hoped a technology as disorienting and destabilizing as AI might finally force them to reopen. Shaking socialists out of their conceptual stupor was, at any rate, what my original essay set out to do.

Here are some of these questions: (a) Is freedom separate from necessity—a reward that arrives after the vegetables have been eaten—or must it be found within and through necessity, as a quality of action rather than its terminus? (b) Is action itself divided into two modes—instrumental work on one side, everything else (play, ritual, communication) on the other—or do we need a more expansive conception, one that refuses the dichotomy as a relic of an industrial order we claim to be transcending? And, (c) how do these choices map onto each other—as two realms (of necessity and freedom) matched to two modes of action (of work and non-work) or under some other configuration entirely—and at which intersection should socialism plant its flag?

On the first question, Marx’s famous passage in Capital, Volume III has set the terms for over a century. The “realm of freedom,” Marx writes, “begins only where labour which is determined by necessity and mundane considerations ceases; thus in the very nature of things it lies beyond the sphere of actual material production.” The shortening of the working day is the “basic prerequisite.” Read one way, this is a promissory note: Handle necessity now, cash in freedom later.

Yet Marx’s own formulations refuse to sit so neatly. In the very same passage, he insists that freedom within necessity “can only consist in socialised man, the associated producers, rationally regulating their interchange with Nature, bringing it under their common control… under conditions most favourable to, and worthy of, their human nature.” Self-government in the labor process is itself a condition of freedom, not merely its prelude. Across the Marxian tradition there exist heterodox readings—hardly unserious, whatever the gatekeepers mutter—that insist some freedom must already be possible within necessity, even if the full realm of freedom demands structural transformation and a wholesale rewiring of what we’ve learned to need.

But notice what even the heterodox readings leave untouched. Whether freedom comes after work or within it, “work” itself remains a stable category—a distinct kind of activity, analytically and historically separable from rest, play, care, ritual, communication. The industrial imaginary frames the horizon. The question is only where to locate freedom relative to labor; the question of whether “labor” names a coherent and transhistorical kind of action never arises. The factory bell still rings, even if what happens on either side of it is rearranged.

Benanav plants himself firmly in two-realm territory—and has done so explicitly. In his book Automation and the Future of Work, he dismisses thinkers who imagined that the distinction between realms could be collapsed. “Here I leave to one side,” he writes in a footnote, “thinkers like Charles Fourier, William Morris, and Herbert Marcuse, who essentially suggested that the collapse of spheres could be achieved by turning all work into play. Single-realm conceptions of a post-scarcity world are, in my view, both totalitarian and hopelessly utopian (in the bad sense of the term).”

Note the logic. Benanav considers exactly three thinkers who proposed collapsing the two realms. All three, in his reading, wanted to turn work into play. From this sample of three, he concludes that all single-realm conceptions are totalitarian and hopelessly utopian. The syllogism is revealing: The only alternative to the two-realm partition he can imagine is one in which play swallows work—and since play is unserious, such visions must be either escapist fantasy or, somehow, totalitarian. That other single-realm possibilities might exist—that work and freedom might be fused through something other than play—does not appear to cross his mind. (In the NLR essays, Benanav institutionalizes his earlier equation of the “realm of freedom” with the “realm of free time”—a move that strips Marx’s view of its debt to Hegel: the conception of freedom as self-actualization through activity.)

But here’s what Benanav seems not to have noticed: The neoliberals got there first—and went the other way. For the likes of Hayek and Milton Friedman, there are no two realms. The market is not merely necessity’s domain but freedom’s very medium (cue the title of Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom). Through consumer choice we satisfy our needs and fashion our identities; through entrepreneurship we innovate and realize ourselves. The neoliberal utopia is not deferred to some post-scarcity horizon—it is already discernible in the capitalist present, wherever the market operates unimpeded. Freedom is not what happens after the vegetables; freedom is the meal.

This single-realmism of neoliberalism is ideologically monstrous, of course. But it is also strategically brilliant, and Marxists have never found an adequate response. Benanav’s answer is to double down on the two-realm partition, as if the only alternative to neoliberal market monism were a return to the safety of separate spheres. His footnoted dismissal reveals the assumption: single-realm = play replaces work = unserious = totalitarian. But this forecloses precisely the question that matters. Why must the “other” of instrumental action—or we can call it “work,” “labor,” or even “poiesis”—be play? Why not praxis—formative, end-generating, creative action that is neither the drudgery of necessity nor the escapism of leisure? And if such action exists, why must it be cordoned off in a Free Sector, kept safely away from the machines? And are we correct to assume a duality where, perhaps, all action is pregnant with creative potential, so a single, more expansive concept would serve us better?

These are not newfangled questions imported from pragmatism or sociology to trouble an otherwise settled Marxist account. They are Marx’s own questions—and he never settled them. Marx himself oscillated between the possibilities I have just sketched, and the oscillation was not a scholarly inconvenience to be smoothed over with a footnote. It marks a political fork in the road, and which path you take determines what socialism is actually for. If freedom is essentially what happens later—the payoff after the machinery has been rationalized—then the socialist task becomes the efficient organization of production, with creativity safely relocated into leisure, culture, or some post-scarcity horizon shimmering beyond labor’s end. Administration now, imagination later. If, however, freedom must also happen now, within necessity, then the task shifts radically: Institutions must cultivate forms of action in which new ends and new values emerge inside materially mediated practice, not as constraints downloaded from some deliberative cloud.

But there is a deeper ambiguity in Marx that the realm question merely indexes. His account of action itself—the shifting, unstable vocabulary of work, labor (both abstract and concrete!), activity, praxis—is even less settled than his account of how necessity leads to freedom. Are work and labor the same thing or different? Is praxis a subset of labor or its transcendence? Does ”free conscious activity” name what we do after work or what work could become? Marx never resolved these questions, and neither has the tradition that claims his name. The theory of realms and the theory of action are entangled: How you draw the boundary between necessity and freedom depends on what you think human doing fundamentally is, and vice versa. Get one wrong and you will get both wrong.

What Marx did leave room for—and this is crucial—was the possibility that the associated producers, once empowered to govern their own activity, might choose to direct their energies toward ends other than rising productivity and shorter hours. They might pour resources into care, conviviality, ecological restoration, or forms of making that never fit comfortably under the heading of “efficient production.” The deliberative space for such choices was always already present in the Marxian framework.

In this sense, Benanav’s proposals—benchmarked against the failures of the Soviet model rather than Marx’s theory—are not that novel. He resolves Marx’s twin ambiguities—about realms and about action—in a characteristic and revealing way. Thus, Benanav spatializes what is, in Marx, partly temporal and conceptual. The two-realm gradient gets flattened into a zoning map. The Functional Economy handles multi-criteria production under binding constraints; the Free Sector provides a “structured space” for political, cultural, and associational life, explicitly linked to a “realm of freedom beyond economic necessity.” And the theory of action gets resolved by fiat: Inside firms, instrumental rationality reigns; Investment Boards, in contrast, are the oases of communicative rationality.

At this point the family resemblance to early Habermas becomes impossible to ignore—a resemblance of which Benanav himself seems unaware. Habermas tried to rescue Marxism by cleaving two modes of rationality with a meat axe: instrumental and strategic action (the systems of economy and administration, pervaded by technological rationality) on one side; communicative action (the stuff of norms, publics, deliberation) on the other. This dichotomy rests on a prior distinction that Habermas makes between labor and interaction.

This is also exactly where Habermas was attacked—and not only by hostile critics sharpening knives from across the aisle, but by students, allies, and initially sympathetic theorists who had expected something more. The complaint was never that purposive action matters less than discourse; it was that socially mediated doing cannot be exhausted by the binary of “means-end control” versus “discursive justification.” The world is not cleanly divided between mute technique and eloquent deliberation. There are forms of embodied, tool-mediated, inventive practice that generate norms without being merely communicative or merely factory-bound. A pragmatist-inflected theory of action pushes the point further: Creativity is internal to action as such, woven into its fabric, not a special property reserved for discourse, art, or the sandbox sectors of the economy. (The sociologist Hans Joas is the canonical reference here.)

Benanav repeats, perhaps unwittingly, Habermas’s wager and builds an entire economy around it. In its monumentality and systematic ambition, his theoretical apparatus resembles nothing so much as an unexpected sequel to Habermas’s The Theory of Communicative Action—one that finally specifies how the Keynesian economy would actually function once the conditions for the ideal speech situation had been secured. Benanav has, in effect, produced a theory perfect for governing the Germany of the 1970s. This is not a minor achievement. But it is an achievement whose moment has passed.

For just like Habermas, Benanav cannot account for forms of action that are neither instrumental nor communicative. The binary admits no third term. Habermas, when pressed, shunted such possibilities into the aesthetic domain—his equivalent of Benanav’s “play.” In his early debate with Marcuse over technology and emancipation, Habermas went so far as to claim that any technology supporting non-instrumental forms of action belongs in the romantic realm of poetry and mysticism rather than that of science—a definitional fiat that ruled out in advance what it could not theorize. (It is precisely this fiat that my own recent work on ecological intelligence has sought to contest. Benanav, apparently, cannot discern its significance.)

The result is a familiar two-step dressed up in new institutional clothing: Optimize instrumental action under multiple criteria, create deliberative fora where workers can debate and self-govern, and sooner or later—once the machinery hums and the hours shorten—freedom will arrive. Benanav problematizes the deliberative aspects more than most; I grant him that. But the basic schema remains intact. The machine room takes orders from the boardroom, which takes orders from the town hall. A tidy chain of command, if you don’t look too closely at the links—or ask whether the machinery itself might be doing something other than taking orders.

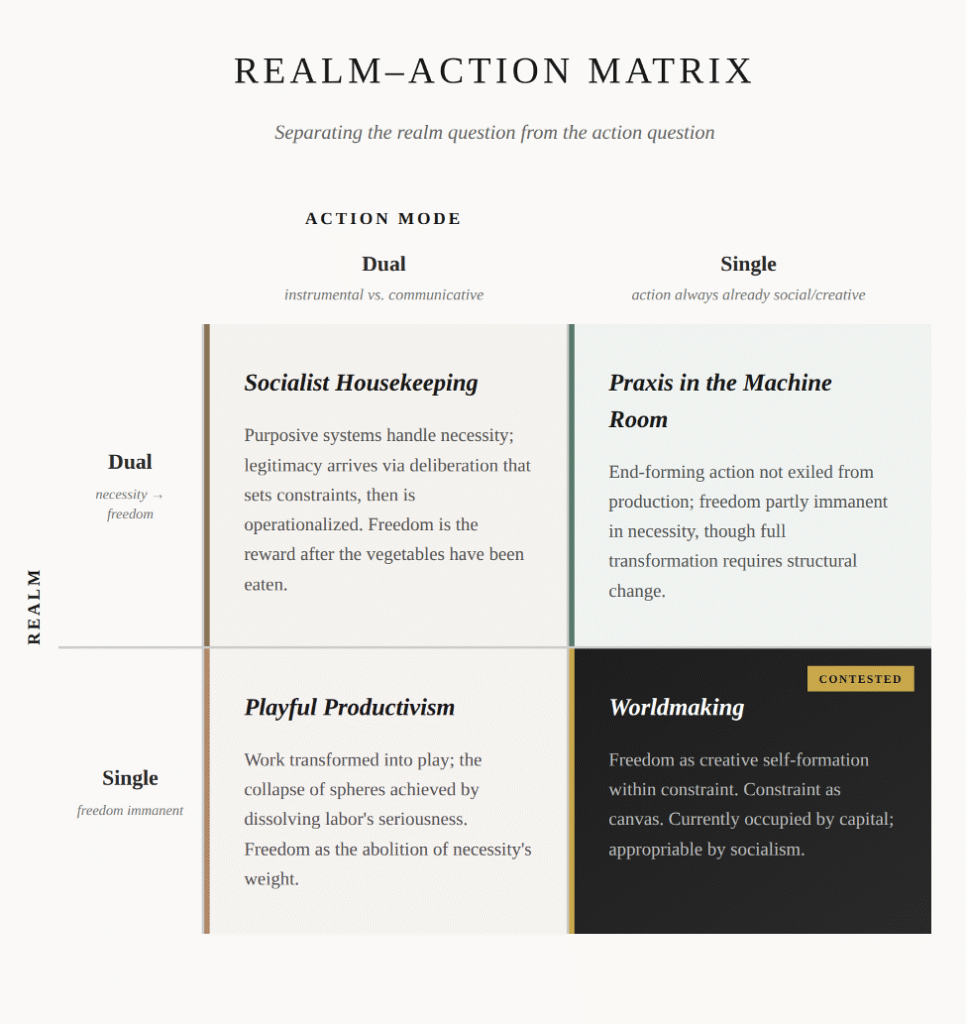

If you pry apart the realm question from the action question, the underlying commitments snap into focus. The grid below—all coinages are mine—maps the terrain:

What matters for the polemical stakes is what this grid reveals. Benanav plants socialism firmly in the upper-left quadrant (“Socialist Housekeeping”): the two-realm, dual-action settlement. Purposive systems here, normativity there. Necessity and freedom in separate rooms, communicating by memo. It is a defensible position—Habermas has defended it—but it is a position nonetheless, not a neutral description of how things must be.

Without a theory of action, Benanav is blind to the “Worldmaking” quadrant. All his discontent gets shunted into “Playful Productivism”—the only exit his framework can find. Yet, it’s precisely on the terrain of Worldmaking that neoliberalism has learned to manufacture its legitimacy. Not by promising that freedom comes later, once the bills are paid and the planning is complete, but by offering a lived sense, right now, today, that constraint can be a medium of creation, experimentation, and self-fashioning. The promise is often fraudulent. The distribution is grotesquely unequal. But the experience is potent—and potency, in politics, is not nothing.

AI does not invent this shift; it intensifies it, miniaturizes it, democratizes the feeling of it. Capitalist AI—and we do not yet know any other kind—is the most powerful delivery mechanism ever devised for the sensation that your constraints (which today might even take the form of LLM tokens) are your canvas. My bold bet is that the theoretical problems posed by AI to their own project might eventually force socialists into noticing the Worldmaking quadrant and, perhaps, even reclaiming it from the neoliberals.

Once the battlefield snaps into focus, Benanav’s reading of the Socialist Calculation Debate reveals itself for what it is: a man showing up to a knife fight with a slide rule. He writes as if the debate were still frozen in the von Mises-Hayek-Lange-Neurath moment of the 1930s—a gentlemen’s quarrel over whether socialist institutions could replicate the market’s capacity to allocate scarce resources efficiently under constraint. That is precisely the frame in which Investment Boards and trade-off procedures look like checkmate. The trouble is: The game moved on while Benanav was still polishing his pieces.

By the late twentieth century, the craftier neoliberals had already switched sports entirely. Not by offering yet another proof that markets calculate better—that vinyl was scratched—but by redescribing what markets are for: a rule-system enabling bounded experimentation without any “external” objective (efficiency least of all) against which the whole contraption could be scored. The economists James Buchanan and Viktor Vanberg, in a seminal 1991 provocation, fittingly titled “The Market as a Creative Process,” compressed the move into a paragraph that deserves to be tattooed on the forearm of every socialist still jousting with Hayek’s ghost:

The market economy … neither maximizes nor minimizes anything. It simply allows participants to pursue that which they value, subject to the preferences and endowments of others, and within the constraints of general “rules of the game” that allow, and provide incentives for, individuals to try out new ways of doing things. There simply is no “external,” independently defined objective against which the results of market processes can be evaluated.

Read carefully, this is not an argument about efficiency so much as a refusal to play on efficiency’s court. Ends are not given; the target is not sitting there waiting to be hit; the future is generated through constrained trial, error, learning, and institutionalized surprise. Allocation doesn’t vanish—it gets demoted, from philosophical master key to one constraint among others inside a grander claim about freedom. What legitimizes capitalism, in this telling, is not the elegance with which it distributes goods but the laboratory it provides—the market as political infrastructure and collective daydream—for individual self-discovery and reinvention.

The move preemptively disarms planning fantasies, AI-powered or otherwise. Omniscience of even the perfect planner, no matter how benevolent, is beside the point when the goods don’t yet exist in anyone’s head. Buchanan and Vanberg:

Omniscience would, of course, insure access to any and all knowledge; benevolence could be such as to match the objective function precisely with whatever it is that individuals desire. But even the planner so idealized cannot create that which is not there and will not be there save through the exercise of the creative choices of individuals, who themselves have no idea in advance concerning the ideas that their own imaginations will yield.

No wonder Buchanan ended up writing essays on “becoming” and namechecking the philosopher-mathematician Alfred North Whitehead—the same Whitehead whom Deleuze, of all people, called “the last great Anglo-American philosopher.” The intellectual genealogy of the Socialist Calculation Debate is stranger than Benanav, perusing the texts of the 1930s, seems to realize. Process ontology, becoming over being, the irreducibility of creative novelty—this wasn’t Paris in ’68 but public choice theory in Blacksburg, Virginia. The right was reading process philosophy while the left was still debugging its input-output tables. (The philosopher John O’Neill, whose work informs much in Benanav’s own account of the Socialist Calculation Debate, did notice the Buchanan-Vanberg article and the broader “radical subjectivist” trend that it represented; however, he dismissed it as being of little relevance to economics. This certainly might be so, but the true relevance of that project has always been in politics.)

That post-Hayekian twist is what Benanav barely registers—if he registers it at all. Neoliberalism, in its wilier iterations, stopped defending the market as an allocation or even information-processing engine and started marketing it as a bridge between necessity and freedom. Freedom exercised inside necessity, through constraint, in the form of projects, experiments, self-creation under rules. Entrepreneurship shed its gray flannel suit as a means-end technique and emerged, blinking in the California sun, as the name for purposive action that also generates ends. The Socialist Calculation Debate, in other words, was sublated—Aufgehoben, lifted and cancelled, the whole Hegelian two-step—by Hegel-hating neoliberals, not the Hegel-admiring Marxists who should have seen the move coming.

And here the factory-firm inheritance of Benanav-style Marxism waddles back onstage, dragging its industrial luggage. Castoriadis, the heterodox Greek-French philosopher and a one-time functionary of OECD, once observed that orthodox Marxism reads the entire human history “as a series of increasingly less imperfect attempts to achieve that ultimate perfection, the capitalist factory.” Benanav offers precisely that structure in freshly laundered form: greener, more democratic, multi-criterial—and still factory-centric to its bones. The firm remains the privileged container of purposive action and innovation, the only vessel sturdy enough to hold serious work. Everything else gets relegated to a cultural margin—a greenhouse where values may germinate but must eventually be transplanted into enterprise soil, translated into the grammar of objectives and deliverables, before anyone will water them.

AI is the first technology in a generation that destabilizes this inheritance at the level of everyday possibility. It makes the firm less self-evident as the unit of creativity; it smudges the line between poiesis and praxis until the border guards can’t tell who’s coming or going; it turns tool-mediated practice into a medium of end-formation, not just end-pursuit. In that sense, AI forces Marxism to confront what it has long postponed with the diligence of a graduate student avoiding his dissertation: What are institutions supposed to do with non-instrumental action? How do you valorize it—with time, resources, recognition, durable supports—without squeezing it back into the same enterprise grammar, filing it under “objective” and assigning it a key performance indicator?

Neoliberals, unbeknownst to most Marxists, have been mining this ground for decades—their pickaxes swinging while the left was busy attending to its footnotes. This is where Silicon Valley matters: not as a colorful anecdote, not as the latest capitalist circus to gawk at, but as the practical apparatus that turns the neoliberal redefinition into lived experience. Markets as infrastructures of self-creation are no longer merely argued in seminar rooms and libertarian newsletters; they are technologized, packaged, and placed in the hands of users with the frictionless ease of a software update.

Generative AI is the most intimate delivery mechanism of that promise—it compresses the distance between intention and execution until the gap feels less like a chasm than a crack in the sidewalk, and it makes constraint feel like a medium of invention rather than its enemy. When someone fires up a tool like Claude Code—Anthropic’s AI agent that lives in the terminal and writes working code from natural-language commands—to prototype a project, they are not playing in some sanitized opposition to working; they are acting in a mode that dissolves the boundary between necessity and freedom like sugar in hot water. The activity is serious, embedded in constraint, tethered to the real—and yet experienced as worldmaking. That cocktail is potent, and to pretend otherwise is the kind of wishful thinking that has cost the left more than a few rounds.

This is not a defense of Silicon Valley. God knows the place needs fewer cheerleaders and I’m certainly ill-positioned to audition for that role. It is a diagnosis of why its promise has bite—and why a socialism that answers with “boards will deliberate” lands with all the seductive force of a tax form. Meaning does not arrive by vote, like a parcel from the municipal warehouse. You do not deliberate yourself into a form of life. You enact one; you discover it; you inhabit it; you fight over it; you become capable of it. The procedural cart cannot precede the existential horse.

And this is the point that Benanav’s design cannot reach, no matter how many criteria he stacks on the dashboard. His apparatus is exquisitely built to adjudicate trade-offs—a Swiss watch of socialist deliberation, every gear in place. But trade-offs are not an ontological given, handed down from the mountain. What counts as “scarce,” what counts as a “resource,” what counts as a “competing use”—these are historically produced meanings before they ever become inputs into an investment function. They arrive pre-chewed by the world that made them thinkable. Sometimes the most radical act is not choosing between two options with the wisdom of Solomon, but making the choice irrelevant by creating a third world in which the dilemma no longer binds (did I already mention that Marxists should read more Hegel?). That is what worldmaking names: the capacity to generate new affordances, new practices, new ends—rather than perfect the governance of existing ends under scarcity, like a very enlightened landlord optimizing the arrangement of deck chairs.

I must confess to having an autobiographical stake here, so let me lay my cards on the table before someone else does it less charitably. I have lived this arc. There was a time—it feels like a previous geological era now—when I treated the Socialist Calculation Debate as salvageable, a contest the left could still win if only we built better coordination mechanisms, shinier planning tools, more elegant matrices. The socialism-as-superior-spreadsheet fantasy. By 2020, the scales had fallen. The deeper problem was not missing machinery; it was a confusion about the two realms and a matching theory of action—about how institutions cultivate transformative capacities rather than merely distribute burdens and adjudicate trade-offs with the solemnity of a divorce court.

Benanav, naturally, pounces on this retreat. He accuses me of gesturing toward “desirable features of a socialist future without any account of the institutions capable of sustaining local experimentation or coordinating collective transformation.” The man wants blueprints; I’ve handed him a mood board. Fair enough, as far as it goes. But notice what the accusation assumes: that the blueprints are what matter, that the institution-building is the serious work, and that anyone who declines to play architect is merely waving from the sidelines.

My reluctance to connect the dots that Benanav takes such evident pride in connecting was not laziness or oversight. It was the dawning recognition that this is mostly a fool’s errand: Why exhaust yourself trying to win a 1930s version of the debate when the neoliberal camp has already sublated the whole affair and moved on to greener pastures? Benanav chides me for dabbling in cybernetics and for praising Saros’s digital socialism—research programs he dismisses as “exhausted” or “ill-suited to the task.” He may even be right. But the lesson I drew from those detours was not that I needed to try harder at mechanism design. It was that mechanism design, however exquisitely executed, cannot answer the question that actually needs answering.

That is still where I stand in 2026, even though I did eventually solve many of the puzzles I wrestled with when writing the NLR piece Benanav references. The solutions just turned out to matter less than I had hoped—less so than Benanav still hopes his own will matter.

And it is precisely why Benanav’s response—so determined to prove he has a mechanism for every objection, a procedure for every complaint, like a man frantically patching leaks on a ship whose hull is already underwater—only strengthens my diagnosis. He wants to know where my Investment Boards are, my sectoral coordination committees, my five-year mandates. I want to know where his account of legitimacy is; his theories of desire, action, or ideology; his explanation of how any of this becomes something people would fight for rather than merely accept or tolerate. The more comprehensive the machinery, the more conspicuous the absence it was built to conceal.

Evgeny Morozov is the founder and publisher of The Syllabus. He is the author of The Net Delusion and To Save Everything, Click Here.